The Strike of the Vilne Street-Walkers

- Written by:

- Avrom Karpinovitsh

- Translated by:

- Shimon Joffe

- Published:

- Fall 2013 / 5774

- Part of issue number:

- Translation 2013

Known for his intricately detailed and lively short stories about Jewish life in pre–World War II Vilna, Avrom Karpinovitsh (1913–2004) was a leading figure in the Israeli Yiddish literary scene. Karpinovitsh’s family was among Vilna’s artistically most accomplished; his father, Moyshe Karpinovitsh (1882–1941), was a founding member of the city’s Yiddish Folk Theater. After surviving the war in the Soviet Union, Karpinovitsh settled in Israel in 1949, where he worked as a manager of the Israeli Philharmonic Orchestra in Tel Aviv. In his later years Karpinovitsh was a frequent visitor to Lithuania, where a plaque dedicated to his father’s memory now stands.

An excerpt from Vilne mayn Vilne

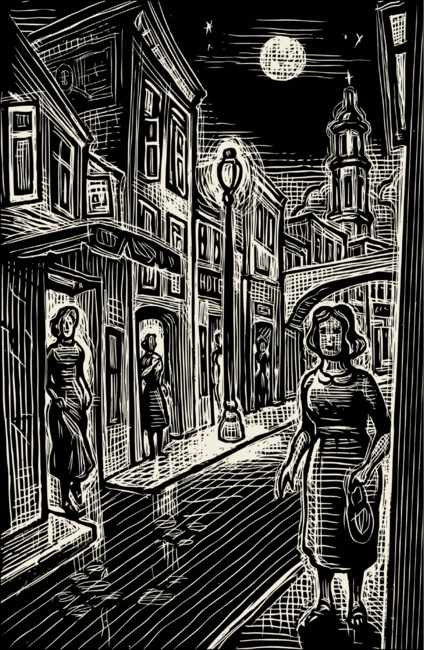

The whole affair began with Foul Bertha, who kept a “house” on Yatkever Street, and there was not one girl in the brothel with whom she had not quarreled. Altogether, she had a big mouth and a filthy tongue. Vilna never forgot how she, Foul Bertha, berated Tall Tamara and belittled her because she had allowed a steady customer, the porter Hershele, to stay an extra while. Foul Bertha delivered Tamara a lecture: a “house” is not a place for lovemaking. The business demanded a system of “in and out,” and no messing about with a guest, even if he were the Graf Potocki himself. When the red lamp is alight over the door it says, “Come in and provide a living.”

Foul Bertha did not just talk, she shouted, as she was certain that she wasn’t heard. Otherwise she was an ordinary woman, with a neck and smooth cheeks. The problem was that she was deaf in one ear, and that ruined everything. In years past she too was of the profession, walking along Koleyove Street near the railway station waving her handbag about as a sign she was free and available.

The other brothel keepers, like Hirshel Canary, Tovshe the Angel, Esterke with the Glasses, and others in town, claimed that the troubles were due to Bertha’s Frenchified ways. After the affair with Hershele, Tall Tamara left her. Bertha then took in Small Head Zoshke. Zoshke had her steady clientele and was as quiet as a mouse, didn’t say a word, even when a crude fellow was too lazy to take off his boots and dirtied the sheets. Business was brisk at Bertha’s and income was good. But one day a Jew, not a local, came in to lie with Zoshke. She saw he was huge — the leg of a stool seemed like a matchstick compared to his. She was afraid he would knock over the furniture. Zoshke had the nerve to say she would not lie down for him. This was most unlike her. The Jew pulled up his trousers and left the brothel, slamming the door behind him. Foul Bertha ran after him and asked, “What’s the matter?” and the Jew gave her a tongue lashing. He said that she, Foul Bertha, should be ashamed of herself, keeping such a tramp in the house, and he was going to Tovshe the Angel’s on Sophianikes Street. There he’ll be treated like a king and not discriminated against.

Foul Bertha, boiling with fury, went at Zoshke and gave her hell. The latter tearfully explained the reasons why she would not receive her guest. On hearing this Foul Bertha exploded as usual and held forth. “With me you don’t measure; here you don’t use a ruler,” and here she added a few more words about Zoshke: that her mother was ashamed to spread her legs when she lay down because she had pimples there, and that is why she, Zoshke, emerged with such a small head.…

As is known, all those who have chosen to eat the bread of affliction, who stretch out the hand to take what is not theirs or give an eye at the street corners, all the toughs and knife wielders — the moment their mothers are insulted, they are prepared to carry those rude people out of town in small packages. Bertha cut Zoshke to the quick by casting aspersions on her mother’s honor. She, like Tall Tamara a few months earlier, packed her bits and pieces in a wooden chest she had brought from her home and left to seek another address.

Small Head Zoshke wandered about for many days with her wooden chest up and down the Sophianikes Street, near Wileyka Stream, full of Vilna “houses,” until she found a sort of refuge near the end of the street, close to the old fish market. Moneywise, this was a poor location, being somewhat remote and far from the nearest street lamp, but then, she had no choice. Foul Bertha had bad-mouthed her, saying that she had begun to pick and choose her guests, this one yes, that one no. So as a result not one of the brothel keepers was prepared to have her in his “house.” The other ladies of the street, particularly Dark Leyke and Yudesl, couldn’t bear to see her in such straits and slipped some zlotys into her hand to help her through this hard time. Were it not for these two, Zoshke would have had to put her teeth on the shelf, as the saying goes, and simply starve.

In the early evenings, before Sophianikes Street began to bustle, the chattering women stood in the entrances and gossiped. The soldiers hadn’t yet left the barracks, which stood some distance away on Piramont, on the other side of the big river Viliya, to revive themselves with a bought tender touch. Now the women in their chattering held forth about Foul Bertha’s foul mouth, which showed no respect for anyone, as if the ladies of the profession were the last human dregs on the cobblestones, as was sung in the play Money, Love, and Shame in the Jewish theater. All the streetwalkers attended the theater and were overcome by the scenes.

All this would not have been enough to get the streetwalkers to declare a strike. They had suffered many a blow in the past. They would have somehow continued to go on in their misfortune and continued with their wretched business. But the Vilna brothel keepers had decided to raise the bed charge. The streetwalker had no rights to her room. She had to pay the brothel keeper for every guest, and no argument. This was called a bed charge in the profession. Now she was expected to pay more than half her takings to the owner. No matter how she skimped, what was left was barely enough to subsist on. Nothing left for a dress or a ribbon. Not enough left to send a few guilder home.

The decision to raise the bed charge came at a very bad time. Not only did they have to contend with Foul Bertha’s filthy tongue, but now came the additional new demands of the brothel keepers. This was too much even for those who had bowed their heads in the past just so that they would be allowed to have their four or five solid guests each night and be able to push a few hard-earned zlotys into their little wooden chests.

At this juncture Siomka Kagan appeared and stoked the fire. Siomka Kagan was a journalist who worked for the newspaper called the Vilner Tog (the Vilna Daily). He was well acquainted with Dark Leyke, as he had on one occasion hidden himself from the police in her room on Sophianikes Street. Siomka was a leftist, striving to bring the Soviet social revolution to Vilna. But as such revolutionary thinking was forbidden in Poland, the police kept their eye on him. They wanted to send him to the camp for the politically suspect that had been constructed at Cartuz-Bereza. Siomka, he waited out the tumult and the searches with Dark Leyke, who mothered him and fed him into the bargain.

Siomka always had various plans connected with the white slaves, as he called the streetwalkers in his newspaper articles. He had planned at one time to organize them into a professional union, as was customary in Vilna. There was a doctors union, a cobblers union, a bespoke tailors union; so why shouldn’t there be a union of streetwalkers?

After this scheme fizzled out, Siomka thought up another one — to open a school of love. Dark Leyke and Tall Tamara were to be the teachers. Nothing came of this scheme either. Now that he learned of the demands of the brothel keepers about raising the bed charge and also about the ruckus with Foul Bertha and her filthy tongue, Siomka came to life. He felt that this was a rare opportunity to demonstrate to Vilna the power of socialist unity, and the cry of the masses would be heard.

The Bernadine Garden was splendid in all its multiple colors. The brown, ripe chestnuts shone like the eyes of satisfied creatures. They hung from their age-old trees among the green leaves and begged, “Pick us before we fall to earth, make ink of us with which to write love letters.” The sun, like a burnished copper plate, moving westward, painted the horizon a delicate reddish hue and fought against the sunset hour about to start. Summer also lay like liquid gold poured out on the white feathers of the pair of swans who quietly paddled with their feet in the pond in the center of the garden.

There Siomka called together a meeting of the Vilna streetwalkers to urge them to come out in an open struggle against their exploiters, the brothel keepers. The place was well known to them all, for in summer the Bernadine Gardens served as the best possible address in which to couple with a guest without having to pay bed charge. The green grass between the bushes was finer than the softest of mattresses.

Dark Leyke organized the meeting at Siomka’s behest. Even though Siomka considered himself a defender of the oppressed, not all the members of the profession were known to him. The girls sat on the ground near the pond, and Siomka stood before them. He cleared his throat a few times and began to speak. “Victims of filthy capitalism! You are exploited by everybody — the brothel keepers, those damned exploiters, use your situation to lay hands on your hard-earned income! They intend to raise the bed charge so you will slave away all night for those bloodsuckers, such as Tovshe the Angel or Khayke the Ruptured. Rise up and deliver them a proletarian no! Use the last and only weapon left to the working man! Let us, here in the Bernadine Gardens, declare a strike! Down with the brothel keepers, the oppressors, and as for Foul Bertha, who does not respect the honor of the proletariat, we have a separate account to settle with her.”

Some of the victims of filthy capitalism cracked pumpkin seeds and whispered that if a well-to-do guest were to appear this evening, here, next to the pond, it would answer a lot of their troubles, including the planned strike.

Like all Siomka’s plans, the one concerning a strike of the streetwalkers, which would set the city on fire, didn’t quite work out. Here and there the girls struck, even set pickets before some “houses,” especially before that run by Foul Bertha, whose business they wanted to ruin because of her filthy mouth. Siomka Kagan did not take into account the fact that brothels in Vilna also existed in other streets besides Sophianikes Street. In the outlying suburbs a gentile opened a brothel crowned with three shikses. The Jewish women really did strike, shared their last morsel with each other, tried somehow to survive, but those shikses and others like them, as at Handsome Mishke’s on Gabarske Street, they laughed at the world and lined their pockets.

Although Handsome Mishke did not suffer from the strike he nevertheless demanded most strongly that they should find a compromise. He had one girl who had been a nun. Mishke, when in a genial mood, related that a priest had seduced her, and this so excited her appetite for men that she went to the Ministry of Health on Zheligavsky Street, registered herself as a prostitute, received a black book, which was a sign of legitimacy, and went each week for a checkup to make sure she did not contract that well-known disease. What is more, this ex-nun used to receive her guests in silk knickers and a racy brassiere, and this, before all else, got the men pulsating in their loins. And so at Mishke’s there was always a queue of the town worthies, and the coins just kept rolling in.

Handsome Mishke, like Siomka Kagan, decided to call a meeting of the brothel keepers in this case, and to discuss with them how to find a way out of the situation. Mishke had a great name among the owners of the brothels. Firstly, because his “house” was among the most highly respected in town. Secondly, he had traveled and got to know the world. Before he had opened his “house” he used to travel on the international trains and used special cigarettes to put passengers to sleep and make off with their luggage. He had already been to the four corners of the Earth and had much to tell. Anyone who dared tell such tales after a drink or two would be dismissed unceremoniously, but Handsome Mishke was listened to.

The brothel keepers sat in Zelig Do-Good’s pub and Mishke held forth. “This is no way to handle matters. Since God has seen fit for us to make a living through whoring, then let us carry on our business quietly and without attracting attention or talk. It should never have come to this, that a whore should go on strike like some washerwoman. Our profession needs calm; everything should run quietly and solidly. I propose we have a go at Siomka Kagan, cut him down to size and deny him any future access to Sophianikes Street. And as for you, you shouldn’t fleece the women too much.”

Having heard Handsome Mishke, the brothel keepers downed his words with a glass of shnaps, and for dessert they chewed on pieces of roast kishke, of which Zelig’s wife was the great specialist in Vilna. Tovshe the Angel, one of the more respected brothel keepers in Sophianikes Street, took the floor. “You can talk, Mishke, your nun has the best guests, but we are not doing too well. The sixth regiment has been reorganized; the soldiers have been transferred to somewhere near Warsaw. The whole street lived off them. Now that there are fewer clients we are left with our tongues hanging out. What does a whore need but a box of face powder, a pair of stockings, a couple of zlotys for her pimp, whereas we have expense upon expense, the house and the bedding and repainting the walls before Passover. In addition, we have to slip an occasional bribe to a policeman to stop him from writing a report when a drunk runs riot or when a guest finds himself beaten up without cause. They want to strike, so be it, let them; they’ll soon be left without a single coin in the pocket, and then they’ll start laying like hens . . .”

Handsome Mishke again interrupted. “The take hasn’t become smaller because the soldiers of the sixth regiment were taken away from Vilna; your income has dwindled because you are not marching with the times. For years now, no outside lamp has been alight on Sophianikes in the evening. The better sort of guest doesn’t want to come here because of the gloom. In Amsterdam, I saw whores sitting in the windows naked, knitting sweaters. A man walking by goes in heat! It is high time such a custom was introduced into Sophianikes Street, and then you will see the whole town lured into the street. The lusting youths will dribble with excitement.”

The girls won but one thing out of this strike: the money they made after midnight was entirely theirs. The brothel keepers gave in. At Mishke’s request, they all agreed with him that Vilna cannot permit itself such goings-on. It may bring about strife and unnecessary quarrels — the quieter the better. Mishke’s suggestion that women sit naked in the windows was turned down — this broth was a little too rich for the brothel keepers’ digestion.

Siomka Kagan was not satisfied with the outcome of the strike. The revolution boiled in him. But he consoled the underdogs, as he called Dark Leyke and her friends, that salvation would come from the East, where the sun of the Stalin constitution shone most bright. From there, the ruin of all the exploiters and bloodsuckers would come. There, women don’t sell their bodies for a crust of bread; there, everybody works honestly milking cows and turning screws.

And so it came to pass. Siomka Kagan did not have to wait for salvation. Some three months later Soviet tanks freed the masses from the yoke of capitalism as they clattered over the Vilna Bridge. It didn’t actually come to this, that the streetwalkers should turn to productive labor such as milking cows or turning screws, as Siomka foretold. The very opposite — now they were busy, overwhelmed with work, but in their old profession. The incoming officials asked for three things: leather for the uppers of their top boots, watches, and someone to sleep with. Sophianikes Street came back to life. There, Small Head Zoshke now ruled, together with a few worn-out pelts like Fat Yudesl and Feigele with the Headband. The brothel keepers too skimmed cream off the new business.

This was not how Siomka envisaged the bringers of freedom, and he was not the only one. The merchants of Zavalne Street too could not understand what this mad buying was all about. Anything from a faded nightdress to a spool of cotton was snapped up. They asked each other, “Is this how things are over there, in Siomka’s Garden of Eden?” They brought songs though, each sweeter than the other.

They brought something else too, and were it not for Small Head Zoshke, all her friends would have ended up in the isolation ward on Savitch Street, in the hospital for venereal diseases. She warned them to avoid the slit-eyed soldiers; these had brought with them from some faraway corner of Asia a wild, biting clap. The wards in the hospital were full, and Mishka’s nun too was to be found there.

Many years have passed, and the strike of the Vilna streetwalkers is still remembered. Many things about Vilna are also remembered. The Strashun Library is remembered. The Real-Gymnasium, the teachers, the Jewish Theater are remembered, something has been written about all these, so let this too be recorded in print, not to be forgotten: Jewish souls and their strike who, together with all others, met their doom there.

Some years ago, Shimon Joffe was given a birthday present, a book by Avrom Karpinovitsh called Vilne mayn Vilne. He was so taken with the stories that he translated some of them, both for his own amusement and for reading to friends. Since then Joffe has translated many texts for JewishGen, including an article on Vilna that appears in the Encyclopedia of Polish Communities.