Avoid Banal Jokes

A Guide to Colorful Guides in the Center's Collections

While researching a story on Yiddish publishing in displaced persons camps for the next issue of Pakn Treger, I came across two fascinating manuals in our collections: Holtsshnitseray (Woodworking) and Vi makht men aleyn makhshirim far hantarbet (How to Make Your Own Tools for Handicraft). Both books were published by the American Joint Distribution Committee in 1947, and their publication signaled a return to a kind of normalcy for the refugee community.

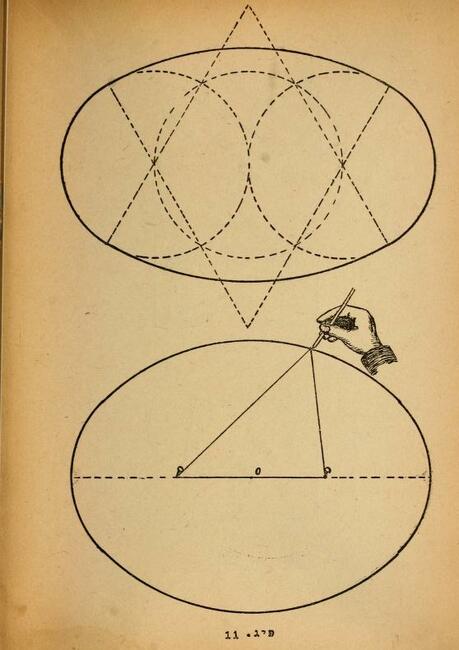

Volumes of histories and literary works mourning the lost Jewish communities were published in the immediate aftermath of the war—and they would continue to be published for some time—but these manuals were practical books published for practical purposes: to teach refugees new skills and to ensure that they had the tools needed to use them. You can see the increasing normalcy just by reading the opening lines of the two manuals. Holtshnitseray opens with a rhetorical flourish—“Great is the joy that comes when one makes something himself”—while Vi makht men aleyn makhshirim far hantarbet goes straight into the advice: “zeyer a sakh makhshirim far hantverk ken men aleyn makhn fun farsheydene opfal-materyaln, velkher zaynen zeyer gring tsu gefinen umetum.” (“One can make a great number of tools for handiwork from various waste materials, which are very easy to find anywhere.”) The description nods to the conditions of the camps, but this is otherwise a straightforward manual, with very useful illustrations and figures.

Vi makht men aleyn makhshirim far hantarbet is one of several fascinating manuals in our Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library. There is the Hantbukh far antireligiezer propagande (Handbook for Anti-Religious Propaganda), published in Kiev in 1927, a selection of texts by Marxist figures on the nature of religion, intended to help the worker understand the true nature of religion, its historical materialist origins, and religion’s role in our culture. It also contains a helpful section on the methodology of anti-religious propaganda for the aspiring practitioner. There is a guide to how to manage libraries (more on this, perhaps, in another post), and there are a number of home economics manuals. One example: Der froys handbukh (The Woman’s Manual) written in 1930 by Adella Kean Zametikin, a guide to living a healthier lifestyle. Zametikin writes with humor and wit, as we see when she introduces the contemporary debate about temperance and prohibition: “az shikern iz shlekht un shedlekh far zikh aleyn un farn mitmentshn, leyknt keyner nit op. afile der shiker aleyn vet dos tsugebn.” (“That getting drunk is bad and harmful to the person and to his companion, that no one denies. Even the drunkard himself will admit it.”)

Perhaps my favorite handbook—ok, second favorite––in our collection, however, is Hipnotizm, sugestye, telepatye: a hantbukh tsu farshtarkn dem viln, feikaytn, un andere gaystike eygnshaftn (Hypnotism, Suggestion, Telepathy: A Guidebook to Strengthen the Will, Abilities, and Other Spiritual Characteristics), published in 1929. The book is a translation of a 1912 Russian volume by Shiler-Shkolnik (or Shiller-Shkol’nik, as it’s sometimes transliterated from the Russian). As far as I can tell, this Yiddish translation is the only translation of Shiller-Shkol’nik’s writing. Both books were published in Warsaw, and the publication of the Yiddish translation speaks to the cultural cross-currents of Warsaw’s interwar multilingual population.

It’s worth emphasizing: this is a serious handbook on hypnotism that will teach its readers how to hypnotize. It contains pearls of wisdom and explanatory statements, viz:

Both hypnotism and magnetism are as old as the world. Hypnotism and magnetism together form one totality. There is only one difference between them, which is that with magnetism one can arouse various feelings in other people, e.g. respect, friendship, love, while the goal of hypnotism is to gain power over others.

סײַ היפּנאָטיזם, סײַ מאַגנעטיזם זענען אַלט װי די װעלט. דער היפּנאָטיזם און מאַגנעטיזם שאַפֿן צוזאַמען אײן גאַנצהײַט, צװישן זײ איז פֿאַראַן בלױז דער אונטערשײד, װאָס מיט מאַגנעטיזם קען מען דערװעקן בײַ אַנדערע מענטשן פֿאַרשידענע געפֿילן, צ. ב. אַכטונג, פֿרײַנדשאַפֿט, ליבע, אין דער צײַט װאָס דער צװעק פֿון היפּנאָטיזם איז באַקומען מאַכט איבער אַנדערע.

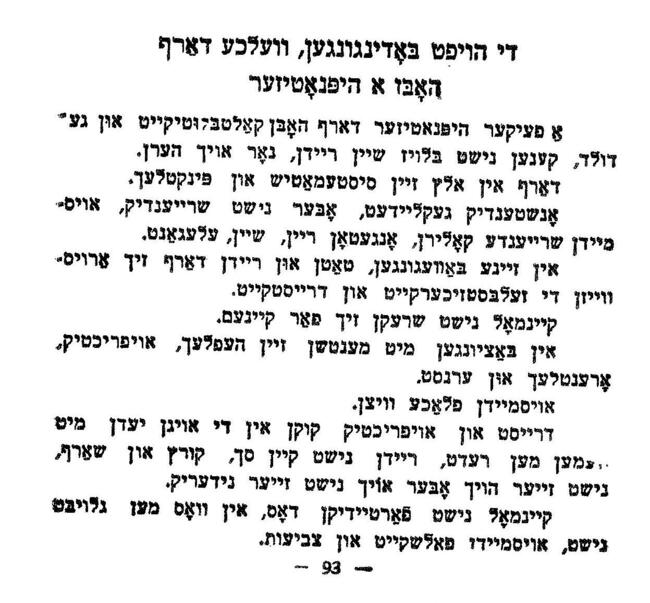

Later, there is a list of traits that determine a successful hypnotist:

“A talented hypnotist must have cold-bloodedness and patience; be able not only to speak well, but also to listen.

Must in everything be systematic and punctilious.

Be dressed respectably, but not loudly; avoid screaming colors; be dressed purely, beautifully, elegant.

Must demonstrate self-assuredness and boldness in his movements, deeds, and speech.

Never be afraid of anything.

Be helpful, responsible, honest, and serious in dealings with people.

Avoid banal jokes. . . .”

Other than a few stray, chilling words, this could be the advice in any number of self-help, success manuals—as we see again in the author’s thoughts on love: “Successful in love are men who possess attractive, elegant figures, who can carry on interesting, flowing conversations. It’s not enough to be good looking and elegant in order to appeal to a woman; rather, one also has to be interesting. Love demands much tact.”

Without practicing the exercises extensively, it’s hard to evaluate its advice as a hypnotism manual. Perhaps it’s as good as any other hypnotism manual. Perhaps Shiler-Shkolnik’s book is a better hypnotism manual. But all these manuals are useful and fascinating and deserve to be studied for what they reveal about their writers and the cultures in which they were written. Like all manuals, they help us to understand the world we live in. They are guides to what we believe and value, and, also, that traits that we idealize and wish to possess. Manuals point the way to physical, spiritual, and moral improvement. The joy of manuals and self-help books is their fundamental utopianism: there is nothing to stop all of us from becoming more spiritual (or less religious, for that matter), dressing better, and eating healthier. We can follow their advice to a more meaningful life. Or, in other words, a more meaningful life is attainable if we avoid banal jokes.

—Eitan Kensky