Black Magic on the Yiddish Stage

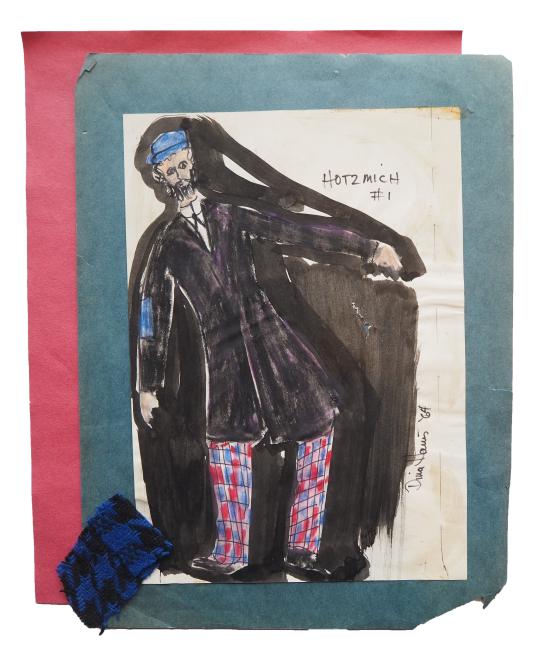

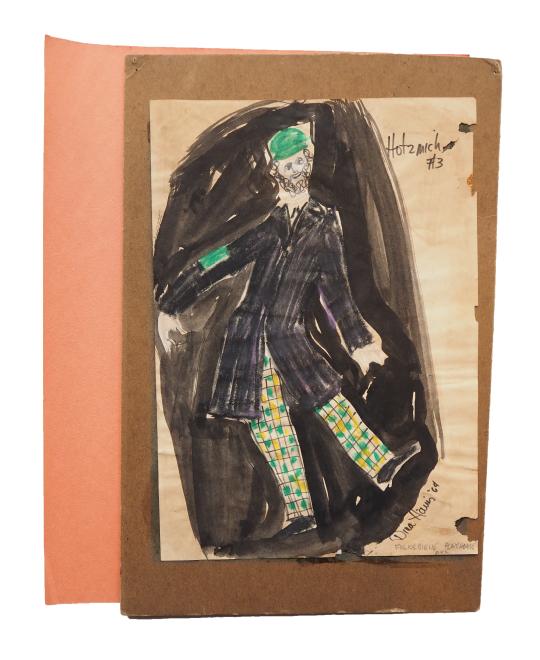

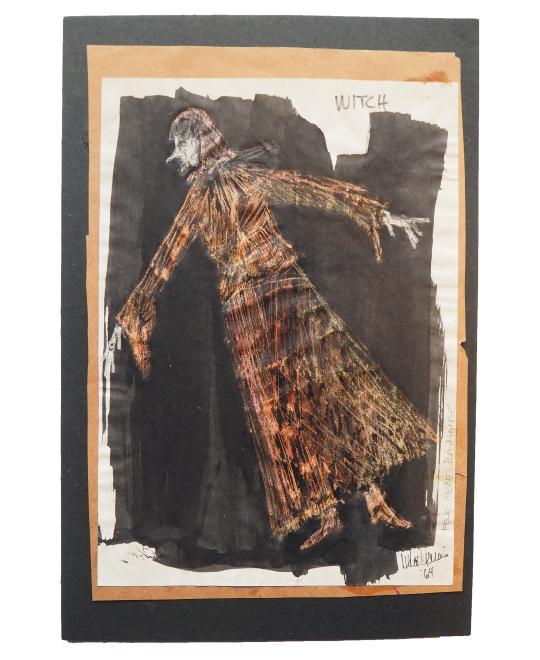

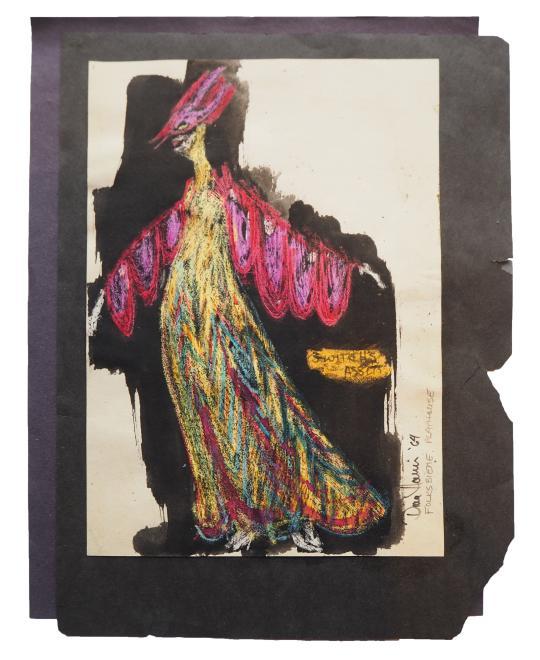

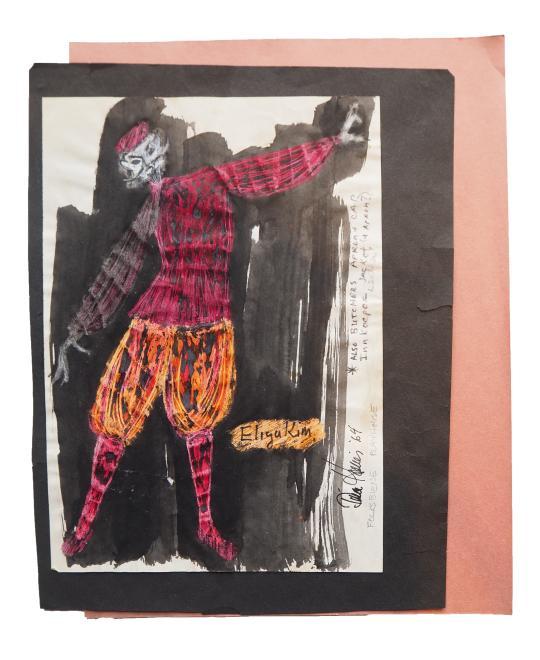

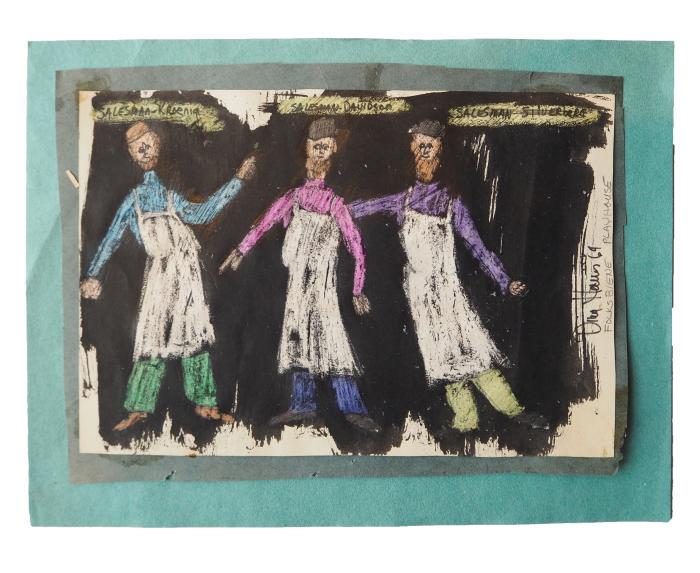

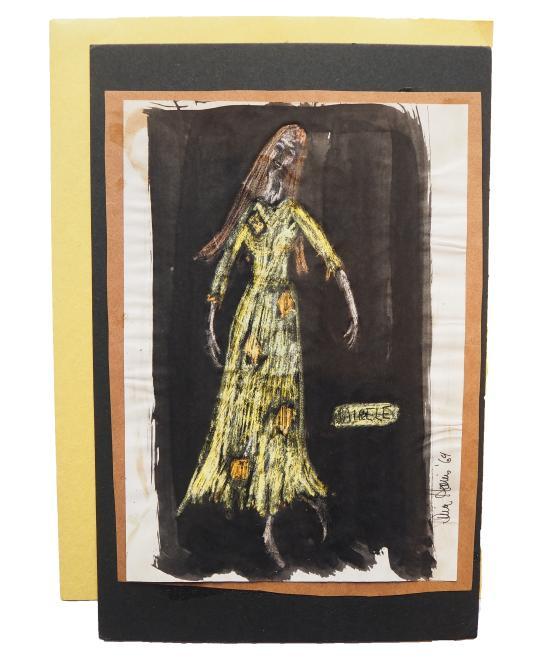

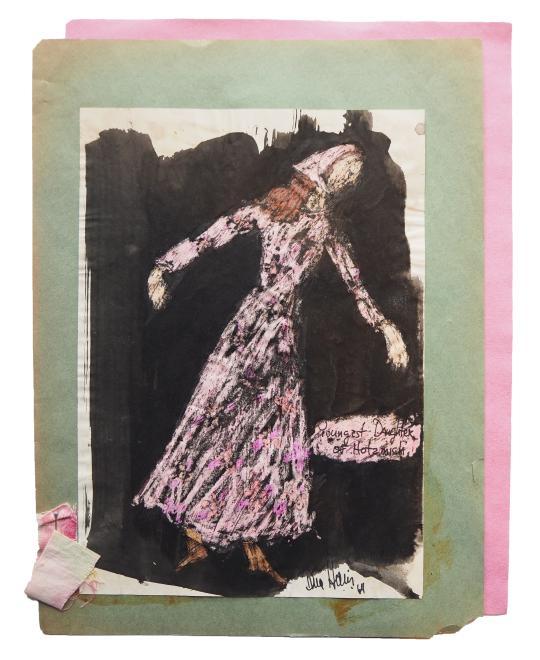

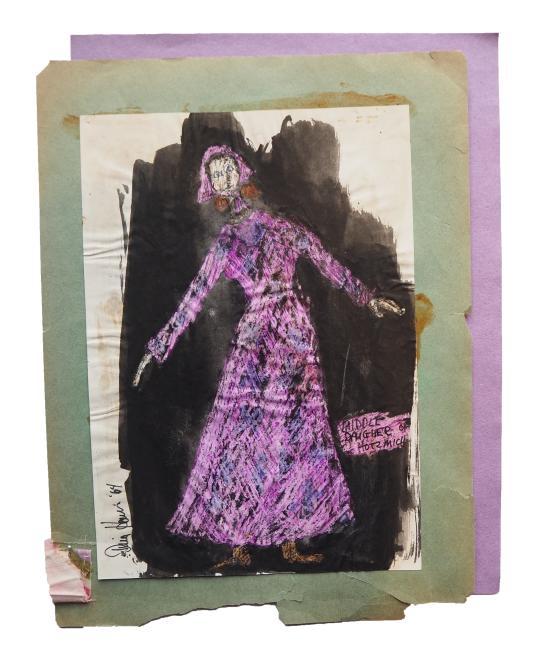

Dina Harris’ Costume Sketches for the Folksbiene

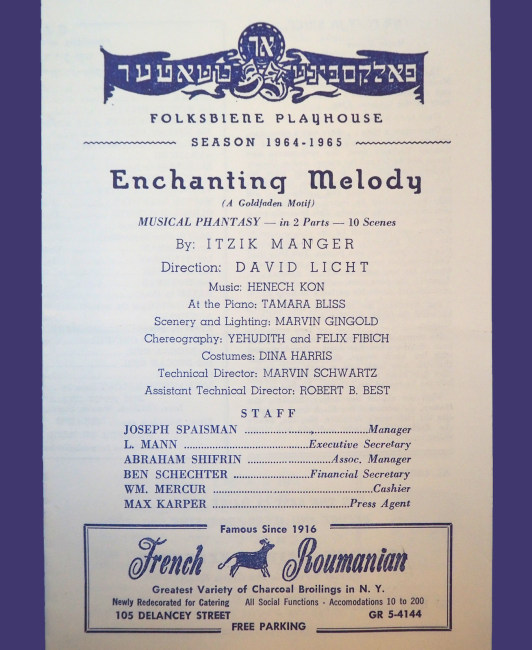

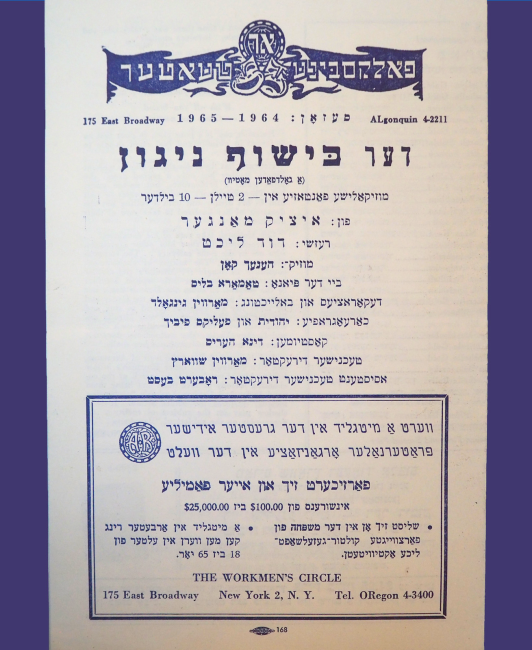

Throughout those long months in the middle of 2020, many of us turned to our closets, attics, garages, and bookshelves, eager to organize. Here at the Yiddish Book Center, we have many such endeavors to thank for an ongoing deluge of donations. One such clean-up project turned up some rather unique objects that now hold a special place in our small but growing collection of ephemera from the Yiddish theater. Dina Harris, a playwright and costume designer based in Wellfleet, MA, was inspired to clear out her attic in search of artwork for a virtual exhibit on the theme of Inspiration & Isolation held by her local public library in the summer of 2020. In particular, she was seeking a series of costume sketches she did for the long-running Yiddish-language theater company The Folksbiene’s 1964 production of Itzik Manger’s Der kishef-nign (Enchanting Melody).

Itzik Manger is best known as a poet—though as a poet he was often celebrated for the musicality and theatricality of his prose. As he describes in the introduction to his one published drama, “mayne kinder-yorn zenen geven ful mit ‘teater’” (“my childhood was full of ‘theater’”). Following his father’s own tendencies toward the theatrical at family simkhes (celebrations), theater ran in Manger’s veins. As a young man, he would hang around after the shows at Avrom Akselrod’s Yiddish theater in Czernowitz, helping to collect chairs and lug props in order to gain access backstage. In interwar Poland, at the Nowości Theatre in Warsaw, Manger staged two productions based on the work of Avrom Goldfaden, the father of Yiddish theater. When he found himself in London after the war, he published a version of these plays as Hotsmakh-shpil: A Goldfaden-motiv in 3 aktn (Hotsmakh-Play: A Goldfaden Motif in 3 Acts).

Some twenty years later, the Folksbiene took up Manger’s Goldfaden motifs and spun from them a magical tale about the enchantress Bobe Yakhne, who teaches the poor Avreyml a farkishefter nign—an enchanted melody—which would make him rich and prosperous, on the strict condition that he share the melody with no one. Later in life, after a wealthy Avreyml teaches his daughter Mirele the nign, Bobe Yakhne appears and makes them paupers once more. We then follow Hotsmakh, another poor man, as he swindles his way through life in order to improve the lot of his daughters. Everyone seeks Bobe Yakhne’s enchanted melody, with all its rewards and all its risks.

A Pair of Hotsmakhs

The Witch's Team

In 1964, Harris was a young costume designer trying to make it in New York City, working mostly off Broadway. She was hired by the Folksbiene to design costumes for its 1964 production of Manger’s magical dramas. Harris is neither a Yiddish speaker nor reader. In the interest of assimilation, her parents forbade her Yiddish-speaking Baba—her grandmother, presumably not herself a maleficent enchantress—from teaching her any. So when it came time to sketch out the costumes, each of the show’s three lead actors sat her down and explained the script to her, “each proclaiming,” she says, “that they were the star.” Despite these star-studded plot summaries, and despite that she so beautifully captures the essence of Manger’s characters, Harris confided in us: “I never did know what the script was about.”

In the Marketplace

Harris created the sketches using a technique known as “black magic,” which produces an effect similar to the rainbow scratchboards you can buy at any dollar store today. A wash of black India ink was painted over a pencil and crayon drawing. After this, the ink above the drawing was scratched out to reveal the shining colors against the black backdrop. The technique, which was popular among children at the time, lends both a childlike sense of fantasy and a subtle eeriness. Thanks to this method, Harris was able to capture the rigid and sinister Bobe Yakhne as she floats mysteriously in the air, the cheery and playful patterns on Mirele’s and her friend Chanele’s dresses, and all the shades of wonder and terror that fall in between. For Harris, this spectrum from the frightful to the delightful reflected the title of Manger’s play. As she put it to us, “I liked working with these materials because I liked the surprises of enchantment. You never really knew how the drawings would turn out.”

Mirele and the Dancing Daughters

Unsure exactly where she had last seen them, Harris began to pull box after box out of her attic until, down to the very last box—farthest from the entrance to the attic, as she recalled to us in an email—she found the sketches! It was a “genuine miracle,” in her words, that the sketches survived this long in her damp Cape Cod cottage. Harris kindly gifted the colorful sketches to the Center for use in our collection of theater materials. Unlike poor Avreyml, we can now share their magic widely.

—Caleb (Shmuel) Sher, February 2023

Caleb (2022–23 Bibliography Fellow) likes to describe himself as an itinerant student. He has an interdisciplinary humanities degree from the University of King's College, Halifax. He also earned an MA with a certificate in Jewish studies from the Centre for Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto, where he held a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) scholarship. Beyond his interest in and growing collection of Yiddish books—the material anchors of Yiddish's literary and cultural history—Caleb is excited about how the internet, from online shmueskrayzn to yidishe memes, plays a fundamental role as the new, virtual anchor for secular Yiddish culture.