The Bund on the Leningrad Trials

A Document from 1970 Illustrates How the Bund Struggled to Position Itself in the Bipolarity of the Cold War

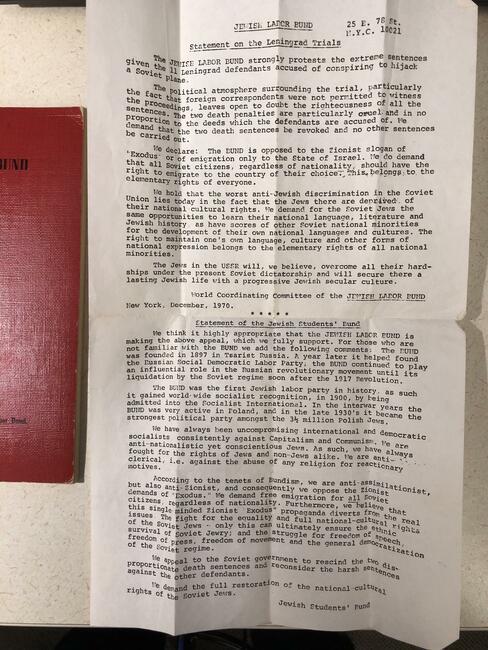

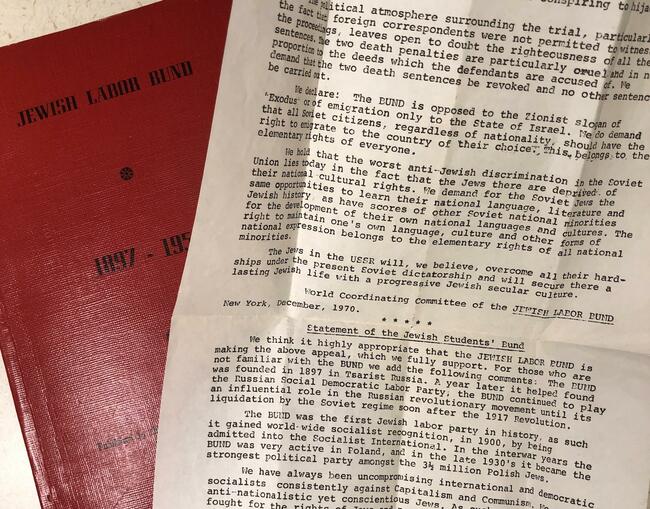

Ephemera of various kinds will often reveal itself to you when thumbing through the pages of any book donated to the Yiddish Book Center. Sometimes, the bookmarks, ex-libri, notes, and flowers pressed between the pages give us clues about the personal lives of the former owners of these books. Other tucked-away surprises can help us understand the state of the world at large—for example, the Jewish Labor Bund’s 1970 Statement on the Leningrad Trials, which fell out of a chapbook commemorating 60 years of the Jewish Labor Bund.

The Leningrad trials were a watershed moment in the history of the Refusenik movement. The fourteen defendants, who were tried for attempting to hijack a Soviet airplane with the ultimate goal of emigrating to Israel, received harsh sentences, including two death sentences. This drew international attention to the condition of Jews in the Soviet Union. The USSR responded to the criticism by commuting the two death sentences that were initially handed down and by shortening the prison sentences of the other defendants. The final defendant was released in 1984.

Many Zionist or apolitical Jewish groups were positioned to offer unequivocal condemnation of the Leningrad verdicts (for example the vigils and rallies held by the American Jewish Conference on Soviet Jewry in response, which drew ten thousand, including members of the Jewish Defense League). However the Bund differentiated itself by using their statement as an opportunity not only to condemn the actions of the Soviet Union, but also to reaffirm their anti-Zionism and their belief that a Jewish cultural revival was possible within the Soviet Union.

The Bund’s negation of both Zionist and Soviet narratives of the affair put them in an unusual position: between two world views in a time, much like our own, where presenting a nuanced political perspective requires a great deal of acumen. As a social democratic organization, the Bund’s anti-Capitalism and anti-Communism left them with very little mass support from anyone—a far cry from its position sixty years earlier when it was founded and quickly became the largest Jewish political party in history, and twenty-five years after the majority of its constituents were murdered in the Holocaust. The extent to which this document was circulated, and its impact, is anyone's guess. But to be clear, at this point in the Bund’s history, their voice was marginal to Jewish discourse if heard at all. The effects of the Six-Day War in 1967 mainstreamed the Zionist, nation-statist conception of Jewish identity rather than the Bund’s program of diasporic cultural autonomy.

The resurgence of academic interest in the Bund today coincides with the international growth of expressly Jewish left wing movements (the popularity of social-democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders among young left-wing Jews, for example). The new Jewish left tends to have many of the same positions that the Bund held: anti-assimilationism, combating anti-Semitism, cultural revival, and anti-Zionism. Popular interest in the Bund seems to be focused on its early history as a mass movement, but there is much to learn from its more recent past in America. Studying documents like this, and assessing responses to historical events across the political spectrum, is a worthwhile activity for Jews today of all political stripes as we navigate the murky political discourse of our own era.

A final point of interest on this document is that it’s entirely in English. Ideological support of the Yiddish language was once a central tenet of the party—but not one stray Yiddish letter appears in this statement, nor in the volume Jewish Labor Bund 1897–1957 in which it was found. It’s not surprising that the piece was written for an English-reading audience, but it does illustrate that the loss of a Jewish language as the vernacular of the Jewish masses made it impossible to directly and exclusively address Jews. Addressing a Jewish audience in English meant that there was no longer a closed Jewish discursive sphere—and perhaps the Bund’s balancing act in this moment was all the more difficult to sustain in the English language.

—Abigail Weaver

************************************

Jewish Labor Bund — 25 e. 78 st

NYC 10021

Jewish Labor Bund

Statement on the Leningrad Trials

The JEWISH LABOR BUND strongly protests the extreme sentences given the 11 Leningrad defendants accused of conspiring to hijack a Soviet plane.

The political atmosphere surrounding the trial, particularly the fact that foreign correspondents were not permitted to witness the proceedings, leaves open to doubt the righteousness of all the sentences. The two death penalties are particularly cruel and in no proportion to the deeds which the defendants are accused of. We demand that the two death sentences be revoked and no other sentences be carried out.

We declare: The BUND is opposed to the Zionist slogan of “Exodus” or of emigration only to the state of Israel. We do demand that all Soviet citizens, regardless of nationality, should have the right to emigrate to the country of their choice. This belongs to the elementary rights of everyone.

We hold that the worst anti-Jewish discrimination in the Soviet Union lies today in the fact that the Jews there are deprived of their national cultural rights. We demand for the Soviet Jews the same opportunities to learn their national language, literature, and Jewish history as have scores of other Soviet national minorities for the development of their own national languages and cultures. The right to maintain one’s own language culture, and other forms of national expression belongs to the rights of all national minorities.

The Jews in the USSR will, we believe, overcome all their hardships under the present Soviet dictatorship and will secure there a lasting Jewish life with a progressive Jewish secular culture.

- World Coordinating Committee of the JEWISH LABOR BUND

New York, December 1970

******

Statement of the Jewish Students’ Bund

We think it is highly appropriate that the Jewish Labor Bund is making the above appeal, which we fully support. For those who are not familiar with the BUND we add the following comments: The BUND was founded in 1897 in Tsarist Russia. A year later it helped found the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party; the BUND continued to play an influential role in the Russian Revolutionary movement until its liquidation by the Soviet regime soon after the 1917 Revolution.

The BUND was the first Jewish labor party in history, as such it gained world-wide socialist recognition, in 1900, by being admitted into the Socialist International. In the interwar years the BUND was very active in Poland, and in the late 1930s it became the strongest political party among the 3 1/2 million Polish Jews.

We have always been uncompromising international and democratic socialists consistently against Capitalism and Communism. We are anti-nationalistic yet conscientious Jews. As such, we have always fought for the rights of Jews and non-Jews alike. We are anti-clerical, i.e., against the abuse of any religion for reactionary motives.

According to the tenets of Bundism, we are anti-assimilationist, but also anti-Zionist, and consequently we oppose the Zionist demands of “Exodus.” We demand free emigration for all Soviet citizens, regardless of nationality. Furthermore, we believe that this single-minded Zionist “exodus” propaganda diverts from the real issues. The fight for the equality and full national-cultural rights of the Soviet Jews—only this can ultimately ensure the ethnic survival of Soviet Jewry; and the struggle for freedom of speech, freedom of press, freedom of movement, and the general democratization of the Soviet regime. We appeal to the Soviet government to rescind the two disproportionate death sentences and reconsider the harsh sentences against the other defendants.

We demand the full restoration of national-cultural rights of Soviet Jews.

Jewish Students’ Bund.