Converts, Bible Scholars, and Yiddishists

The complex stories of missionary translations in Yiddish bibliography

Most Yiddish books arrive at the Center well-thumbed. A rare few are pristine, clearly unread. And then you get the real orphans—books that are torn, tattered, and missing their title pages.

That’s how it was with one recent arrival—a thick squat tome of over 1,600 pages. The book itself wasn’t much of an enigma: the first complete page was titled Bereshis (Genesis) with its familiar opening line: Im onfang hot got geshafen der himel und di erd (In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth). But, the donor wanted to know, when and where had the book been published, and who had translated it?

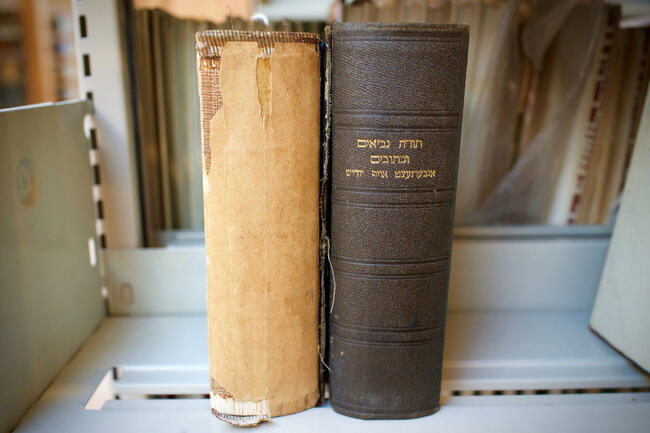

There was one big clue. Tucked into the volume was a torn off strip of binding: Toyre neviim uksovim iberzetst oyf yidish (The Hebrew Bible translated into Yiddish). It was easy to find a similar volume on our shelves. Our orphaned book turned out to be a Yiddish translation of the Hebrew Bible published by the Chicago Hebrew Mission in 1918, and translated by Mordechai Shmuel Bergman. That’s where this trail starts to get interesting—and in an unexpected twist, loops right back to the Center.

Jewish converts to Christianity played a central role in one key area of Yiddish bibliography—translations of the Bible published and disseminated by missionary organizations. For a few decades on either side of 1900, a surprisingly large number of learned ex-yeshiva-students-turned-Christian-converts made new careers as translators of both the Hebrew and Christian scriptures.

Bergman started out like so many other Orthodox Jewish kids in Tsarist-ruled Poland. He passed through kheyder, besmedresh (Torah study house), and rabbinical seminary, before being apprenticed to an uncle to learn shkhite—kosher slaughtering. In 1866 he moved to London, converted to Christianity, and by 1870 he had joined the missionaries. Some years later he began his life’s work of Bible translation, publishing a complete Yiddish version of the Old and New Testaments in 1898.

London, with its well-funded missionary organizations, was something of a magnet for Jewish converts. Aaron Krolenbaum (born Arn Krelenboym) followed in Bergman’s footsteps a generation later. A brilliant Polish-born linguist, he converted to Christianity in the 1920s. Krolenbaum became the Bible scholar in residence at the Mildmay Mission to the Jews, an oasis on the edge of London’s East End complete with lawns, halls, clinics, an orphanage, school, hospital, and living quarters. His Yiddish version of the New Testament appeared in 1949 to considerable critical acclaim.

Then there was Feivel Levertov, born into a Hasidic home in 1878 and a graduate of the prestigious Volozhin Yeshiva. In 1895 he converted to Christianity, married the daughter of a pastor, and in 1918 also took up residence in England. As Paul Phillip Levertoff, he became a well-known “Hebrew-Christian” missionary and translated the Anglican liturgy into Hebrew.

Khaim-Yekhiel Aynshprukh is yet another such figure. Born in the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia in 1892, he grew up steeped in Orthodox Judaism, was active in the Labor Zionist movement and lived in Palestine and Egypt before moving to the United States in 1913. Under his new name, Henry Einspruch, he was in charge of the Lutheran Hebrew Mission and published missionary pamphlets in Hebrew, Yiddish, Polish, Russian, and English. Einspruch’s magnum opus was his 1941 Yiddish translation of the New Testament. As the scholar Yaakov Ariel has noted, it not only “reflected Einspruch’s literary aspirations as a Yiddish writer,” but also attracted praise from the prominent Yiddish writer and critic Melech Ravitch. Encouraging Jews to read it, Ravitch wrote:

"The Einspruch translation of the New Testament is unquestionably beautiful. One feels that the translator is familiar with modern Yiddish literature and that he is a master of the finest nuances of the language."

These Ashkenazi yeshiva students turned proselytizers for Christianity were fascinating characters. Multilingual and theologically sophisticated, they were comfortable frequenting both Jewish and Christian gatherings as well as Yiddish literary circles. And yet they were often viewed by both their old and new co-religionists through a lens of exoticism at best and suspicion at worst.

While missionaries were an occasional butt of Jewish music hall ridicule, the Jewish community saw them as a genuine threat. And with good reason. Conversions may have been hard-won and infrequent, but the warmth of a mission hall amid the chill of winter tempted many poor Jews over the threshold. And missionary services, such as free clinics and medicines, were widely used by Jewish mothers unable to afford doctors’ fees. But few people were lower in the Jewish scale of values than a convert. And the “c” word, neutral in English, takes on a heightened coloring in Yiddish, which reserves a particular edge of contempt for der meshumed. The noun is used for the specifically outcast path of conversion from Judaism to Christianity. But check the dictionaries: its other meanings include: “rascal,” “scoundrel,” and “insolent fellow.”

This is hardly surprising when we consider the company such Jewish converts were keeping. The memoir Our Friends the Jews by the British Catholic missionary Arthur Day is particularly instructive in this regard. Day joined the Catholic Guild of Israel in 1922 and worked for the next two decades in London. His book celebrates a life spent “Jew-baiting.” Published in 1943, it contains just one sentence about violence against Jews, when Day opines:

"A people which has suffered so acutely….at the hands of Christians, must needs be super-sensitive. But gradually it must be borne in on them that their history is not entirely composed of “pogroms” and that these were not always unprovoked."

Arthur Day spent several weeks instructing one particularly high-profile convert: Theodor Herzl’s son. Hans Herzl was received into the Catholic Church around 1925. Soon afterwards, apparently unhappy at the Church’s public rejoicing over its prize “catch,” he renounced Catholicism, moved closer to Judaism, and started describing himself as “a member of the House of Israel.” Prone to increasing bouts of depression, he shot himself in 1930 shortly after attending his sister’s funeral.

As this episode suggests, missionary and conversion stories are full of unexpected twists and turns. Including some happier ones. When I mentioned to Center President Aaron Lansky that I was writing about missionaries, he smiled and told me the story of Einspruch’s Yiddish type:

"Henry Einspruch got a Christian missionary group to fund his translation. They bought him a complete set of Yiddish type, but in the end the book wasn’t published in letterpress; they only ran one impression and then printed it offset. So the type was almost unused; it was a new set. After he died, his wife in Baltimore phoned Jim Kapplin, who was the public relations officer for the Department of Public Works. He also happened to be a great lover of Yiddish and of printing. After Einspruch’s death she had all this type and she offered it to him. And he suggested she donate it to the Yiddish Book Center and that’s how it all ended up here!"

The story doesn’t end there. Michael Yashinsky, Yiddish education specialist at the Center, has become fascinated with Einspruch, calling him “an ardent Yiddishist, devoted to the advancement of Yiddish culture, who also just happened to identify as a Christian.” Michael is currently writing a play about him under the working title Psures toyves (Good News). “The word psure is what Einspruch uses as his translation of ‘gospel,’” Yashinsky explains. “It’s a typical choice for him, a very Jewish word.” If the play is produced, he hopes that Einspruch’s moveable lead type, now at the Center, will be a stage prop:

"He was forced to learn the art of printing himself after all the Jewish printers he approached rejected his requests for help. In my play, I imagine a zetser, a Yiddish typesetter, who is Einspruch’s chief foil. During their conversations, he by turns gives into and then resists Einspruch’s silver-tongued persuasions."

It’s hard not to see elements of tragedy in these Jewish converts’ stories. They were, to use Ansky’s phrase, torn “between two worlds.” But, as our tattered 1918 Bergman volume suggests, those worlds overlapped in unexpected ways. After all, who were the readers of Bergman’s Yiddish translation of the Old Testament? Almost certainly poor immigrant Jews who were more comfortable with mame-loshn (Yiddish) than Hebrew, and who would have welcomed an affordable edition of their holiest book, no matter where it came from.

—David Mazower