A Gift for Jewish Children

Ber Sarin’s Book for Budding Yiddish Speakers

Kh’vel aykh dertseyln a mayse—I’m going to tell you a story. This is a story about storytelling: specifically, a story about the struggle to write stories for Jewish children. It is a story about hope, activism, resistance, and, ultimately, martyrdom. This is a story about a children’s book, and the man who wrote it.

First, some basics. The story of the emergence of Yiddish children’s literature cannot be told without giving due credit to concerns about secularization and assimilation in the interwar years. Miriam Udel notes that this pressure coincided with major shifts in the collective understanding of children as not merely adults in formation but as an audience in their own right and with their own vernacular. All this set the stage for a flowering of books written precisely in order to create a secular, Yiddish-language library serving secular, Yiddish-speaking children growing up in secular, Yiddish-speaking milieus and attending secular, Yiddish-speaking schools.

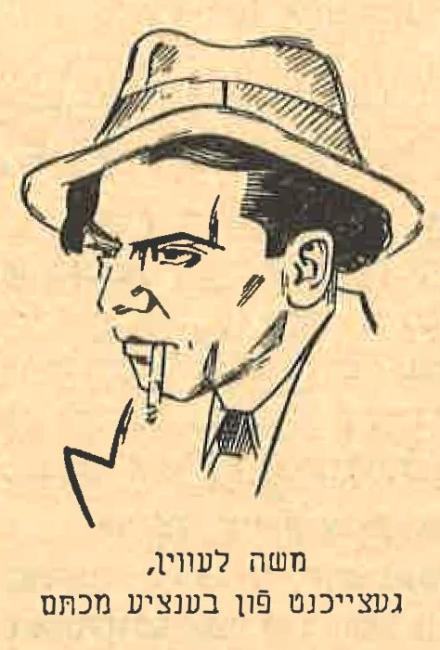

It is on this fertile creative soil that we find a budding Ber Sarin. Biographical details are relatively slim, especially about his early childhood. We know little more than this: Sarin, real name Moyshe Levin, was born in Vilna in 1907. He was the youngest son of a poor glassmaker. He had difficulties hearing—presumably inherited from his father, who was deaf. As a teenager he spent several years wandering around Russia, homeless. He graduated from a Jewish public school in 1922 and entered the Vladimir Medem Teacher’s Seminary in Vilna the following year. According to his friend Avrom Golomb (then director of the Vilna Teacher’s Seminary), it was in those days, while fighting a lengthy battle with his past traumas, that Levin first discovered his ambitions to become a writer and an artist:

At the Teacher’s Seminary he distinguished himself with his capabilities in myriad fields: singing, painting, mathematics, and most of all—with his clarity of mind … Only later did it come to light that his precarious, neglected childhood in Russia left vestiges on his character, against which he fought with great efforts of will.

—Avrom Golomb, YIVO bleter vol. 30 (1947)

אין סעמינאַר האָט ער זיך אױך אױסגעטײלט מיט זײַנע פֿעיִקײטן אױף פֿאַרשידענע געביטן—געזאַנג, מאָלערײַ, מאַטעמאַטיק און דער עיקר—מיט זײַן קלאָרן דענקען … אַרױסגעװיזן שפּעטער האָט זיך, אַז דאָס הפֿקר־לעבן אין זײַן קינדהײט װי אַ פֿאַרװאָרלאָזטער אין רוסלאַנד האָט אױף זײַן כאַראַקטער געלאָזט שפּורן װאָס ער האָט באַקעמפֿט מיט גרױסע אָנשטרענגונגען פֿון װילן.

—אבֿרהם גאָלאָמב, ייִװאָ בלעטער באַנד 30 (1947)

It was no easy fight. During those years Golomb was witness to Levin’s highs and lows and his ongoing emotional struggles—struggles that baffled his classmates, who saw him only as a good friend and capable leader. Yet his difficult upbringing did not keep him from achieving his dreams: alongside his teaching career, he became a member of the Yung vilna literary circle, where he met Avrom Sutzkever and many others. In an elegiac introduction to one of Levin’s works for adults, Sutzkever praises him:

His place as a storyteller rests somewhere between Avrom Reyzn and Dovid Bergelson. But he was Vilna born and raised, in his speech, his style, and his refined humor, and you cannot truly compare him to anyone else.

—Di goldene keyt no. 42 (1962)

זײַן אָרט װי אַ דערצײלער נעסטיקט ערגעץ צװישן אַבֿרהם רײזען און דוד בערגעלסאָן. ער איז אָבער דורך־און־דורך װילנעריש אין זײַן לשון, שטײגער־שילדערונג און זײַן אײדעלן הומאָר, און מע קאָן אים מיט קײנעם ניט פֿאַרבײַטן.

—די גאָלדענע קײט נומ' 42 (1962)

Nevertheless, as Golomb concludes, Yung vilna was not enough for a young Moyshe Levin: “er hot tomed geshtrebt tsu gresers” (“he always aspired to greater things”).

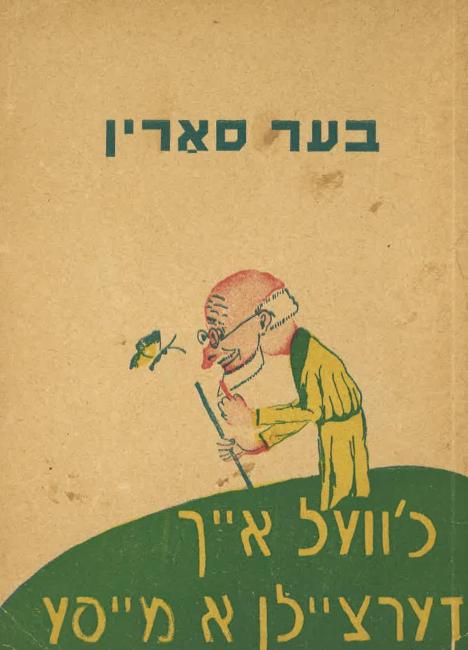

Levin’s impact went far beyond the impression he made on the Yung vilna literati. The audience he sought was much wider. Although he was ultimately barred from teaching in 1934 due to his radical political activism, Levin’s Yiddish pedagogical work did not come to an end. He published a series of eight books for young children in 1937. In his introduction to the postwar edition of Levin’s stories featured in this article, Hersh Smolyar—later a comrade of Levin’s in the Minsk ghetto resistance—describes this publishing endeavor bleakly:

Smolyar goes on to recount how Levin would scrimp and save every groshn (penny) just to get his kid-lit published. And so, out of hardship and with body-and-soul committed to the project of secular Yiddish education, Ber Sarin was born.

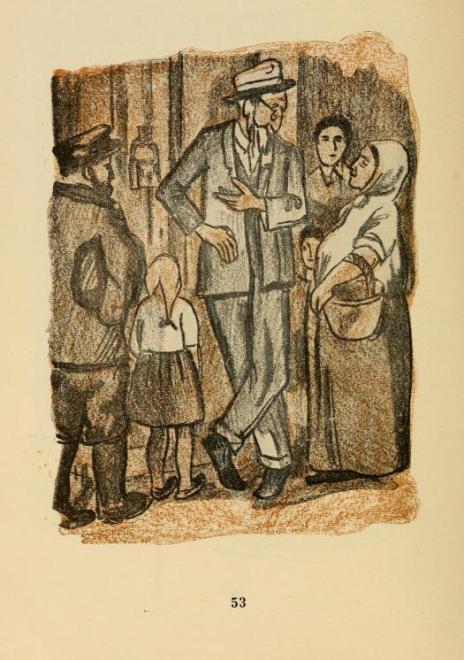

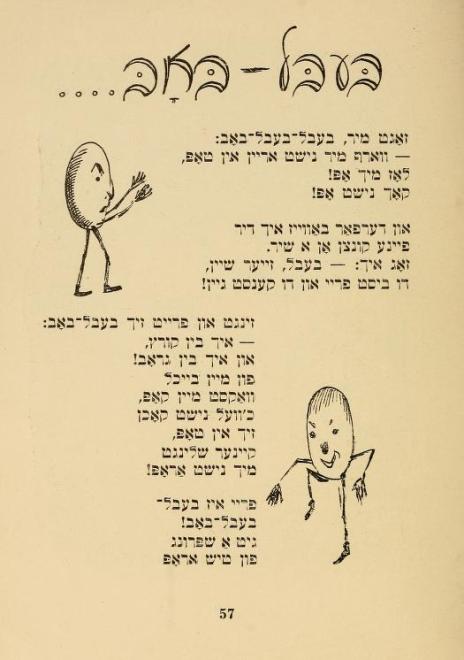

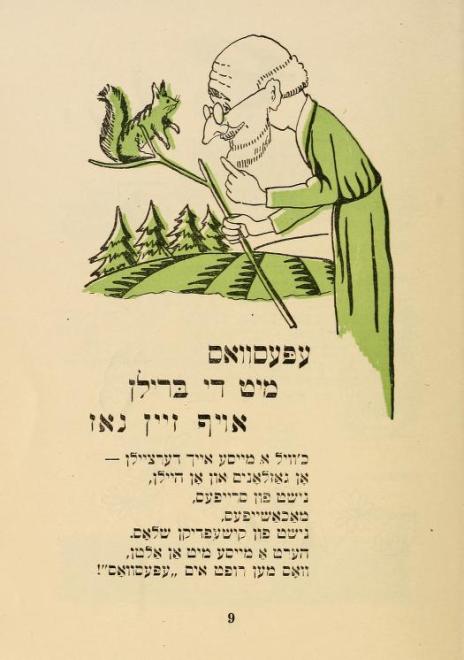

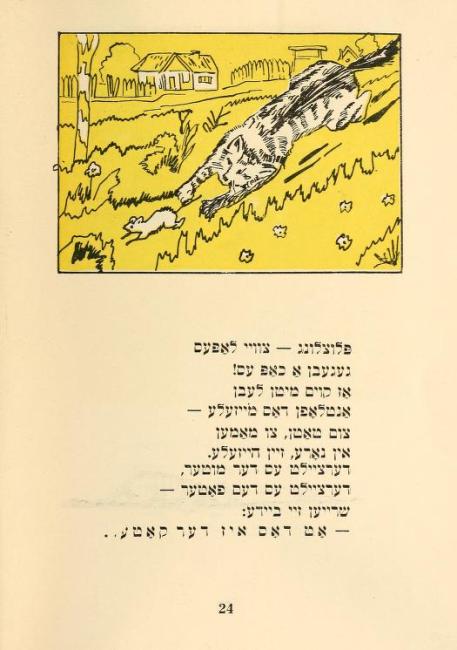

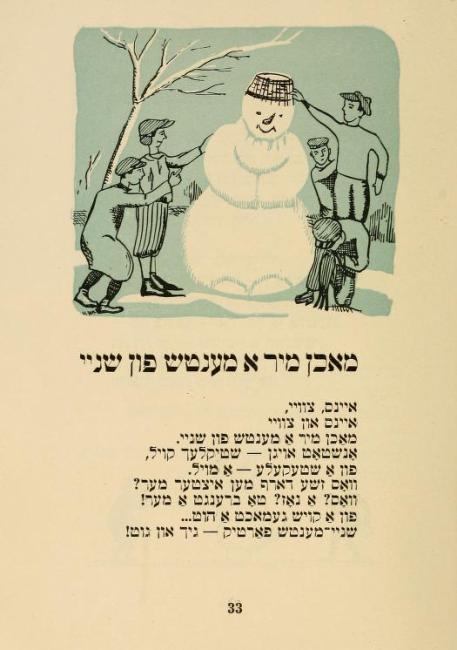

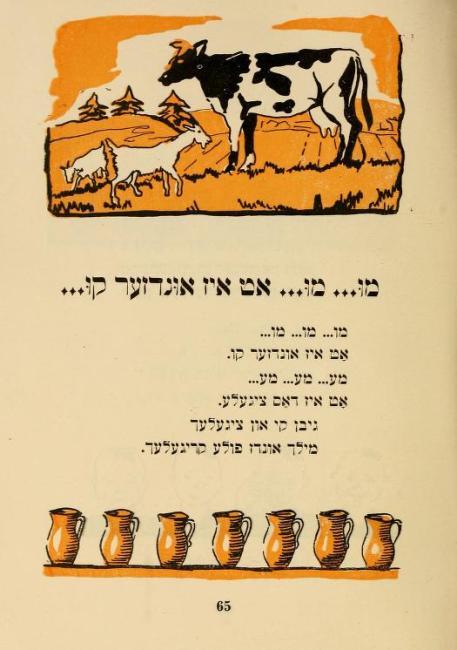

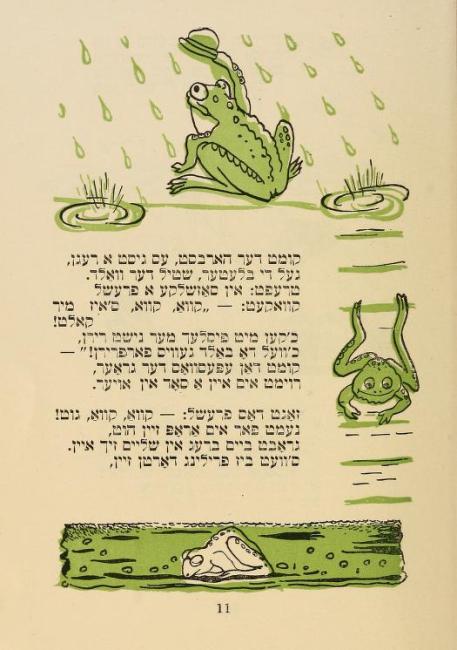

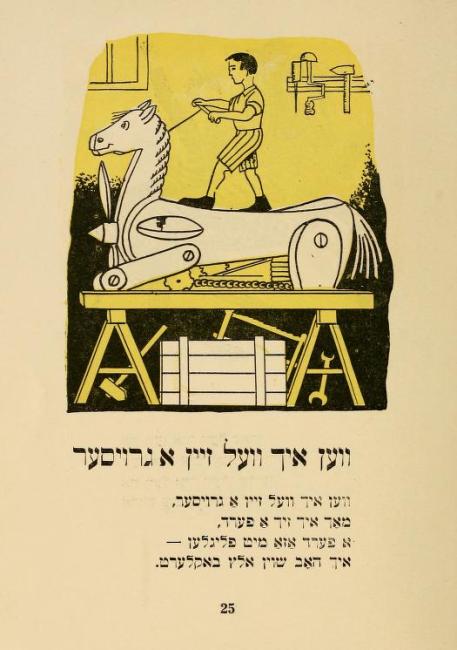

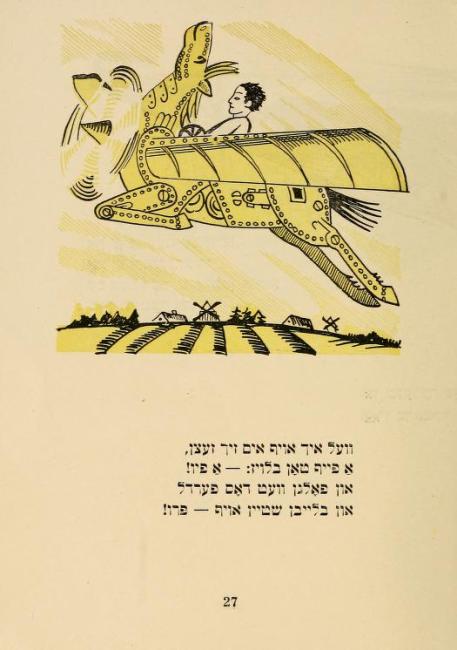

Levin’s Sarin stories—those he wrote under his pseudonym, intended for small children—are full of whimsical characters and happy endings. From Bebl Bob (Bob the Bean), who convinces a child to save him from becoming soup, and Feter Shpeter (Uncle Tardy), the hapless old man who cannot for the life of him get anything done on time, through to Epesvos (Mr. Something), the wise old guide who teaches all the critters how to survive the winter, the characters, and their stories, are charming, universal (there is nothing particularly Jewish about them), and distinctly apolitical. This is especially true when compared, as Shulamith Berger notes, to the books Levin wrote for older children or to the works of his contemporary, the celebrated Yiddish children’s author Leyb Kvitko. To be sure, Kvitko was writing in the Soviet Union—his books had to follow the Communist Party line. Levin was writing in the tense interwar years in Polish-controlled Vilna, where he could not necessarily write so openly about politics; his politics, after all, got him barred from teaching. But both Kvitko and Levin were farbrente radikaln (zealous radicals), and Levin’s works for older children and adults did not shy away from pointing out the faults of interwar Poland’s capitalist autocracy.

Political exigencies of the day aside, Levin’s goal speaks for itself. It was not to instruct his young readers in Jewish religious culture, nor to worry them with the world’s troubles, but simply to inspire in them a love for the Yiddish word. To this end, Levin himself illustrated the books—experimenting, per Berger, with multiple different styles, from watercolor to block prints—and had them printed in full color. They were produced at great personal expense—Smolyar even goes so far as to say that Levin printed and published the books all by himself. (There is a publisher named in the books, but no information can be found about them.) The books were, in a manner of speaking, his gift to the Yiddish-speaking world and to Yiddish-speaking children in particular.

Perhaps this is attributing too much intention to a handful of childrens’ books. I haven’t had the chance to see them for myself; Ber Sarin’s pre-war books are exceedingly rare today. I have yet to encounter one at the Yiddish Book Center—and I wouldn’t be surprised if there are none in our collection. What we do have, and what inspired me to write this piece, is a reprint of several of Sarin’s stories packaged as one larger book, published in 1958 in Communist Poland by the state-aligned publishing house, Farlag yidish bukh.

By the time this book was published, Ber Sarin was no more—and Levin neither. After fleeing Vilna in 1941, Levin was interned in the Minsk Ghetto. In the ghetto, he worked with the underground resistance movement. There he met and befriended Smolyar, who would later edit and write the introduction for the 1958 Yidish bukh edition. The Nazis appointed him as a brigadir, a leader of ghetto work parties, on account of his education and skills. Levin used the position to the advantage of the resistance and helped to convey information about the Nazis’ movements to the partisan groups in the area. As Smolyar tells it, one day Levin heard whispers of a pogrom the Nazis were planning to carry out in the ghetto, so he took as many Jews as possible with him on his work party that morning. On their return to the ghetto, the Nazis stopped the group and told Levin to leave so they could shoot the rest. He refused, saying he would not leave without the rest of his group. On March 2, 1942, Moyshe Levin was shot to death along with everyone else in the work party.

Titled Kh’vel aykh dertseyln a mayse (I’m Going to Tell You a Story)—the first line of the Epesvos story—this posthumous edition is printed modestly with a thin cardboard cover, full of block-printed illustrations overlaid with single-tone blocks of color. It is charming, if somewhat muted. On the surface, it looks much the same as many other children's books of the era. I might have overlooked it entirely were it not for the preface penned by Smolyar. In contextualizing the book both for “tate-mame” (mom and dad) and “zeyere kinderlekh” (their children), Smolyar unequivocally politicizes it too. His preface is seemingly addressed more to mom and dad than to their kids; its prose is simple but still beyond the level of Sarin’s stories for children, and it is replete with vicious, blood-chilling invocations of “hitlerist beasts” and “brown-shirted murderers.” Smolyar’s introduction is nothing short of a hagiography. In it, Levin is elevated to the status of a veritable lamed-vovnik—one of the thirty-six unacknowledged righteous persons who did not seek praise for their just deeds on earth. He is, in Smolyar’s story, the unrecognized hero who:

Levin is, in Smolyar’s eyes, a martyr for Jewish life. Kh’vel aykh dertseyln a mayse is his matseyve, his gravestone. It is a monument to defiance against the fascists who tried and failed to destroy the Jewish future for which Smolyar and Levin both fought.

Yet there is a second hero in Smolyar’s saga, one that still existed at the time he wrote his introduction. The reader is reminded that their gratitude equally belongs to Farlag yidish-bukh, the state-supported Yiddish press of the Polish People’s Republic, which gladly republished the Sarin stories more than 15 years after Levin was murdered by the Nazis. Smolyar describes the 1958 edition in no uncertain terms as a matone, a gift, from Yidish bukh to Jewish children. While Levin gave his life for the future of Jewish children, it is Farlag yidish bukh that preserved his legacy and his work for the future of Jewish childhood. In stark contrast to Levin’s own penny-pinching to publish his stories in late-1930s capitalist Poland, the People’s Republic is painted as liberal in its efforts to fulfill the dream of a robust Yiddish children’s library.

As Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov informs us, however, it was standard practice in those days to thank the Polish Communist authorities for producing and publishing Yiddish culture—a feat that, as Smolyar propagandized, was barely possible in capitalist societies. Still, elsewhere Smolyar does not hesitate to praise the government more widely for its support of Yiddish life. I cannot fully investigate in this short article whether Smolyar’s support for the Polish communist state was genuine or coerced. Nevertheless, while the context of his writing them is an ambiguous period in the history of Yiddish culture, his words reveal what seems to me a passionate belief in the possibility of a Yiddish future in the People’s Poland.

Nevertheless, Smolyar’s political and cultural commitments—and one of his primary outlets for publishing them, Farlag yidish bukh—were not to last. Yidish bukh was established as Dos naye lebn (The New Life) in 1947, so that the newly formed People’s Polish Republic should not fall behind the informal publishing networks of the DP camps in its production of new Yiddish literature. Eventually absorbed into the state apparatus, which gave Yidish bukh consistent funding and support, the press worked on a subscription model. Over the years, the number of subscribers fluctuated (and often exceeded the number of people actually reading the books). As the 1960s drew near, Yidish bukh’s list of subscribers stabilized at around 2,000, down from a peak of about 5,000. The focus shifted from the volume of publication—the claim is often made that Yidish bukh was the world's largest Yiddish-language press at that time—to the quality of publication. Yet, following a decade of low but stable readership, the grand state-funded Yiddish publishing project came to a sudden end with the antisemitic reactionary movement in Poland in the years 1967 and 1968. Along with other major Jewish institutions, unreasonable censorship demands were placed on the press, making it all but impossible to publish Yiddish books. As Poland’s Jews left in droves, Farlag yidish bukh’s doors were finally shuttered in 1968.

Even the farbrenter (zealous) Smolyar was made to doubt his political commitments. While he remained a believer in communist politics, he became disillusioned about the possibility of realizing a Yiddish, communist future in Poland and left for Israel in 1971. And so Smolyar buried the second of his heroes: along with his friend the freedom fighter, the culturally Yiddish socialist project for which he and Moyshe Levin fought.

Our story comes to a close. As Moyshe Levin and Hersh Smolyar’s stories show, passing on the Yiddish word dor tsu dor—generation to generation—has at times been a monumental task. Behind even an innocuous book of charmingly illustrated stories for children there lies a story of hardship and struggle, new beginnings and ends that came all too soon. Thankfully, we can still pick up their books and read: “kh’vel aykh dertseyln a mayse”—“I’m going to tell you a story…”

June 2023

Sources:

Avrom Golomb, "Moyshe Levin (Ber Sarin)," YIVO bleter volume 30, no. 1 (1947), pp. 155-156

Avrom Sutzkever, "A por verter vegn moyshe levin (A Few Words About Moyshe Levin)," Di goldene keyt no. 42 (1962), pp. p. 134-135

Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, “The Last Yiddish Books Printed in Poland,” in Under the Red Banner, Elvira Grözinger and Magdalena Ruter eds. (Wiesbaden, 2008), pp. 111-134

Miriam Udel, Honey on the Page (New York, 2020)

Shulamith Berger, "Moyshe Levin (Ber Sarin) of Yung-Vilne and His Solo Publishing Venture for Children,” Judaica Librarianship 20 (2017), pp. 100–133