The Lives of Yiddish Readers

Ephemera from Our Collection

At any given time at the Yiddish Book Center, there are boxes of books waiting to be opened, treasures waiting to be discovered. These treasures are not purely literary; the boxes of books we receive often contain other surprises as well. Only last week, I opened a book about zoology and natural science—Shmuel Blum’s poetically titled Der boym fun lebn (The Tree of Life)—to find, appropriately, a pressed flower.

Such discoveries are delightfully common here at the Center. In the corner of our Applebaum-Driker theater, the area of our museum dedicated to the Yiddish performing arts, there is even a small exhibit of ephemera in which you will find a number of interesting objects that our staff has found nestled in the pages of books.

Yiddish literature buffs may be tickled to see a set of stamps decorated with the portraits of Y.L. Peretz and Mendele Moykher Sforim, two of the most esteemed Yiddish writers. Also on display is a publishing advertisement for a 1928 anthology of Yiddish poetry by women. There is also an ad for a Yiddish translation of Shakespeare’s sonnets, an important bit of testimony to the fact that Yiddish was a modern language in dialogue with the great canonical works of global literature.

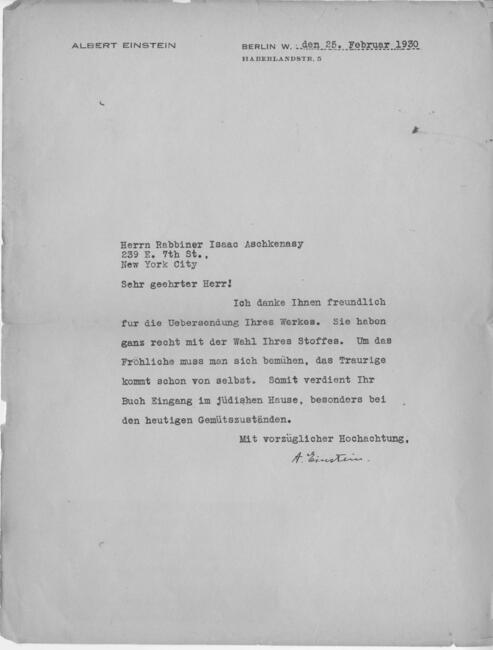

Doctors and scientists may be interested in a multilingual medical phrasebook from a doctor whose practice was just south down the road in Springfield, MA (incidentally, also where my Yiddish-speaking great-grandparents lived), or in one of the objects in the display case that most often surprises and delights our visitors: a letter in German from Albert Einstein. Addressed to Rabbi Isaac Aschkenasy, it thanks him for a copy of his Jewish humor book. With, I think, a particularly Jewish sensibility, Einstein writes: “With enjoyment one has to take trouble, sorrow comes by itself.”

Alongside a pressed flower like the one I found in Blum’s book lies a pressed monarch butterfly, which seems to me an apt symbol for the legacy of Yiddish literature and the work we at the Center do to protect it—a beautiful record of surpassing beauty, perhaps now past its prime, but which we are nevertheless intent on sharing with a new generation and thus revitalizing. There are also more personal objects, such as a unique birth announcement, shaped like a baby’s bottle.

Such objects, to my mind, bear witness to the beauty, texture, and variety of yiddishkayt. They provide fleeting glimpses into the lives of the people who actually owned, read, struggled with, scribbled in, loved, and hated the Yiddish books that the Center works so hard to protect, preserve, and share. They are one of the only insights we have into the lives of our book donors, who otherwise too often remain anonymous, overshadowed by their bookish bequests. Literary history is shaped not just by writers but by readers: though many of us here would like to believe that the story of a culture can be told solely through its books, surely that story is enriched by understanding who read those books, why they read those books, what they thought about them, and what their lives were like. In that sense, these donors are as important to the story of Yiddish literature as the characters in the novels some of them have given us. For that reason, the objects that belonged to them are some of the most valuable objects we hold.

—Miranda Cooper