Yiddish for Esperantists

The klasikers in Esperanto translation, and Esperanto's long Yiddish history

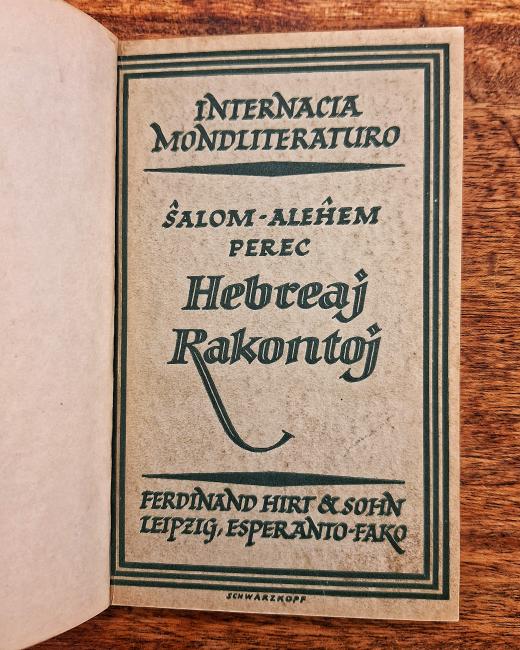

From time to time—between all the sets of the collected works of Sholem Aleichem and peppered among books of lider (poetry), dramen (plays), dertseylungen (stories), etc.—we receive books printed in peculiar alphabets with strange titles and unknown words. Translations, it turns out, from Yiddish into the world’s many tongues. Some into Hebrew, sharing our alef-beys, others into Russian, with its familiar Cyrillic letters, and others still into languages with letters derived from the ancient Roman alphabet—English, French, German, and so on. We can now add to our library of translations the recently donated Hebreaj Rakontoj (Jewish/Yiddish Stories) of Ŝalom-Aleĥem (Sholem Aleichem) and Perec (Peretz), rendered from the Yiddish originals into Esperanto, the twentieth-century artificial universal language aimed at improving relations across linguistic boundaries.

Isaac Mucnik, a librarian hailing from Shepetivka in what is now western Ukraine and later a settler in pre-state Palestine as well as a member of the Esperanto Linguistic Committee, compiled and translated this edition of the klasikers. It was published by the Leipzig-based house of Ferdinand Hirt & Son. Noted mostly for its prolific Esperanto department, Hirt & Son published 50 or so books—Esperanto originals and translations of world classics—from the early 1920s until 1938, when the political situation in the Third Reich forced it to shut its doors. (Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf of Esperanto as a plot to help bring together the international Jewish diaspora.)

That Sholem Aleichem and Peretz were among the great writers and poets selected to help build the library of Esperanto reading materials is no surprise—besides the fact that many of their stories carry a universal appeal in a Yiddish package, the founder of the Esperanto movement and the creator of the language was himself a Yiddish speaker. Dr. Ludwig Lazarus (Leyzer) Zamenhof grew up with Yiddish in his parents’ house (as well as Polish and Russian, to add to the languages he acquired later in life to varying degrees—German, French, Hebrew, Latin, Greek, and English, among others).

Zamenhof’s relationship to Yiddish was complex. As a young man, spurred on by the pogroms of the late 19th century, Zamenhof flirted with Zionism. His Zionism, however, favored a modernized Yiddish rather than Hebrew—he himself wrote a grammar of this new Yiddish, arguing for the romanization of the alef-beys and a scientific spelling system that would avoid ambiguities and homonyms (and all this decades before the YIVO Institute developed its standards). Ultimately disillusioned by the Jewish particularism advocated by the Zionist movement, Zamenhof took leave of Zionism and its language debates. In its place was his vision of a new universalism founded on the basis of his constructed language, Esperanto—a project in which he had been dabbling since his teenage years.

Despite Zamenhof’s political change of heart, the distance between Yiddish and Esperanto—and the ideological movements behind them—is not as great as one might think. Esther Schor has even argued that Zamenhof’s universalist ideology is rooted in Jewish ethics. It is true that although Yiddish was historically the language of Ashkenazi Jewish particularity—the language that separated, for the most part, the Jews from their non-Jewish neighbors—and Esperanto is a universalist project aimed at diffusing interethnic tensions by improving communication and understanding between peoples, there is nevertheless a certain resonance between the two. Both are hybrids; whether intentionally or as a result of the millennium-long migration of a people, both Yiddish and Esperanto incorporate elements of grammar, vocabulary, and style from a variety of European languages and beyond. Both also functioned as lingua francas—Yiddish as the common tongue of Ashkenazi Jews across the globe, Esperanto as a method of communication for all humanity. Yet certain brands of Yiddishism—and Zamenhof’s early Yiddish-inflected Zionism—seek parity for the Jewish people and Jewish culture by making a claim for Jewish difference (in language, religion, and sometimes territory) as the basis for nationhood on par with the emerging nations of late-modern Europe. Esperanto, on the other hand, seeks security for all people through what Esperantists call linguistic justice: by establishing a universal tongue for the public sphere, individuals can maintain their cultural specificity while still overcoming nationalist divides.

Mutually affirming or conflicting ideological intentions aside, Yiddish and Esperanto have a long and intertwined history, as Hebreaj Rakontoj illustrates—a history that goes far beyond the bounds of this short article. For now, suffice to say, our collection is all the richer for the addition of iomete (a bisl, a bit of) Esperanto.

—Caleb Sher, Richard S. Herman Senior Fellow 2023–24

With thanks to Seb Schulman for his mevines (expertise) on all matters Esperanto.