Weekly Reader: The General Union of Jewish Workers

Depending on whom you talk to, “the Bund” could mean different things. It could refer to the historical district along the Huangpu River in Shanghai. It could refer to the German American Bund, an American Nazi organization prior to World War II. But among Yiddish speakers it means Der algemeyner yidisher arbeter bund, or General Union of Jewish Workers. Founded in Vilna on October 7, 1897, the Bund was a political movement and socialist party that existed in different forms at different times and places, including in tsarist Russia and interwar Poland, where it wielded considerable influence. Today it is largely defunct, although there is still a surprisingly large Bundist presence in Australia. Like any political party, the Bund could be controversial—not everyone agreed with its positions, then or now. But it was an essential part of Jewish political history, and of Yiddish as a political language.

—Ezra Glinter, Senior Staff Writer and Editor

Essential Reading

There are a few books in English you can seek out to read about the history and ideology of the Bund, but there are far more in Yiddish, which boasts practically an entire library on the subject. Here are two places to start: the very short, 18-page pamphlet Der iker fun bundizm (Essentials of Bundism) by the Bundist activist and politician Henryk Erlich, and Fun mayn lebn (From My Life), the autobiography of Vladimir Medem, who became one of the Bund’s chief thinkers and ideologues.

Read Der iker fun bundizm by Henryk Erlich

Memoirs of a Bundist

While some of the books written about the Bund were histories or ideological tracts, many were the memoirs of Bundists recounting their time in the movement. One of these, Bernard Goldstein’s Twenty Years with the Jewish Labor Bund: A Memoir of Interwar Poland, was translated by Marvin Zuckerman for English-language readers. On this episode of The Shmooze podcast, Zuckerman discusses his translation, along with stories about his childhood in the Bronx, where he learned how to read and write Yiddish in the Workmen’s Circle afterschool programs and spent time in the company of figures like Chaim Grade, Naftali Gross, and Avrom Reyzen.

In Memoriam

Bundism was far from the only political tendency among Eastern European Jews, but due to its connection with and support for the Yiddish language, it retained a special place in the minds of memories of Yiddish speakers. The importance of the Bund, even after the war, can be seen in the many memorial evenings held at the Jewish Public Library in Montreal. Here, for example, is a recording of an evening held on the 75th anniversary of the Bund, as well as a lecture by professor Sam Kassow in 1997.

Listen to a 75th anniversary celebration of the Bund

Leaving a Mark

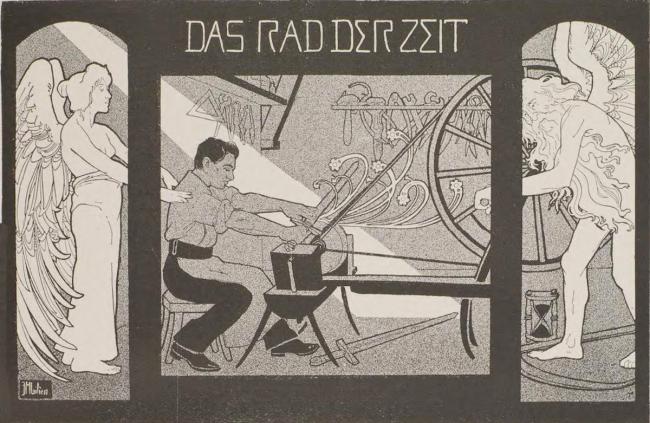

Ephemera of various kinds will often reveal itself to you when thumbing through the pages of any book donated to the Yiddish Book Center. Sometimes the bookmarks, ex-libri, notes, and flowers pressed between the pages give us clues about the personal lives of the former owners of these books. Other tucked-away surprises can help us understand the state of the world at large—for example, the Bund’s 1970 Statement on the Leningrad Trials, which fell out of a chapbook commemorating 60 years of the organization.

Celebrating “Hereness”

The relationship between Yiddishist thinker Chaim Zhitlowsky and the Bund was complicated—although not exactly a Bundist, Zhitlowsky was involved in various Bundist endeavors, and his ideas often, though not always, overlapped with Bundist ones. Perhaps the most important of these is what Bundists called “doikayt,” or “hereness”—the idea that Jews should pursue their future where they already were, rather than, say, Palestine. Although Bundism was primarily a European phenomenon, Zhitlowsky spent half of his life in the United States and significantly influenced both the ideology and the institutional reality of American Yiddishism, particularly through his contributions to the New York Yiddish press and the North American Yiddish supplementary school system.

Bundism Down Under

Like most of Eastern European Jewish life, there wasn’t much left of the Bund after the Holocaust. Nonetheless, offshoots of the organization continued operating for decades in the United States, Israel, and, perhaps more than anywhere else, Australia. In 2017 the Center’s Wexler Oral History project conducted a series of interviews with Yiddish speakers in Melbourne, many of whom come from Bundist backgrounds.