Weekly Reader: The Global Reach of Yiddish Literature

For the past year and more we’ve been talking about Yiddish as a global language. That’s the theme of our new permanent exhibition, Yiddish: A Global Culture, and it’s the subject of an upcoming online class by Professor Ilan Stavans, “The Global Journey of Yiddish Literature.” Although we’ve talked about it before, it’s a subject worth returning to. While it’s easy to think of Yiddish culture as belonging to just a few cities, or countries, or regions, Yiddish-speaking communities existed (and still exist!) in places you might not have realized, and some of the most important and interesting Yiddish cultural activities came not from the big centers but from the overlooked peripheries. Just when you think you’ve heard about all the possible corners and outposts of the Yiddish world, it turns out there’s another one, somewhere, that you never even imagined. To learn more, you can sign up for Ilan’s course here, but in the meantime, read on.

—Ezra Glinter, Senior Staff Writer and Editor

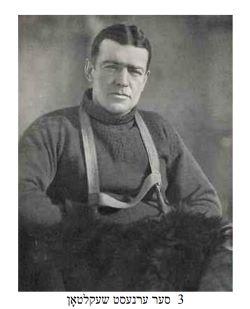

Life among the Penguins

When we talk about the global reach of Yiddish, we usually limit ourselves to the six permanently inhabited continents. But what about Antarctica? While I wouldn’t be surprised to learn of a Yiddish-speaking scientist who has spent time in the frozen south, I have yet to actually hear about one. (If you do know of someone like that, let me know!) However, that doesn’t mean there’s no connection between Yiddish and the seventh continent. In 2011 translator Barry Goldstein rendered some of explorer Ernest Shackelton’s journals into Yiddish—so at least you can read about Antarctica in mame-loshn.

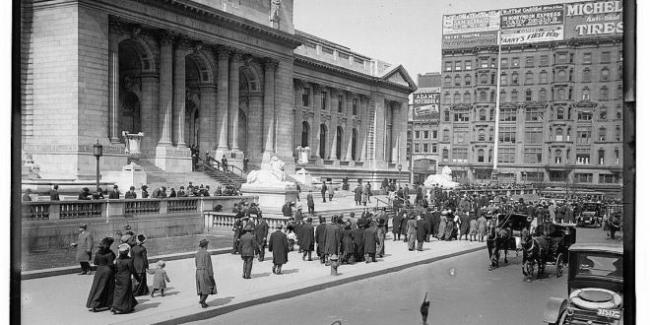

World Traveler

Of all Yiddish writers, Getsl Selikovitsh has one of the most interesting biographies. Selikovitsh was a scholar of ancient languages, and he received a degree in Egyptology. In 1885, he served as an Arabic interpreter for the British military in Egypt, but he left the expedition early after he was accused of sympathizing with the Egyptians. He came to the United States as a professor of Egyptology at the University of Pennsylvania, but he was forced to leave his position on account of “intrigues.” After that, he began a long career as a Yiddish and Hebrew journalist. While little of Selikovitsh’s writing exists in English, here are two pieces that have been translated.

Read “The Small Opinions of Great Men”

Read "The Institute for Facial Reform (A Fantastical Story)"

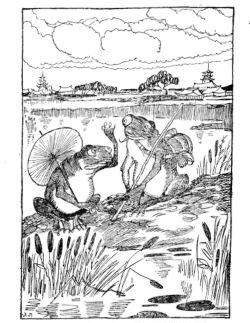

Rising Sun

One of the books at the Yiddish Book Center is a curious volume called Great Jewish American Writers. It includes an entry on Isaac Bashevis Singer, and it’s a testament to his worldwide renown—because the volume, written by Hirose Yoshiji, was published in Osaka in 1993 and is, in fact, in Japanese. This may strike many visitors as an exciting novelty. But Hirose’s book is far from the only commingling of these cultures in the Center’s collection. The Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library contains a number of books with Japan, Japanese culture, or Japanese literature as their subject matter.

Scots-Yiddish

There have undoubtedly been Yiddish-speaking Jews in Scotland. However, has there ever been a real connection between Yiddish and Scottish cultures? The answer, of course, is yes, and it’s not as hard to find as you might think. In 2020 London-based singer Clara Kanter and composer Alastair White created The Drowning Shore, a cantata that threads together Sholem Asch’s 1907 play God of Vengeance with an original Scots-English text. The piece, a fourteen-minute video monodrama, is written and composed by Alastair and performed by Clara.

Life in Bulawayo

There has long been a significant Jewish community in South Africa, but Yiddish life wasn’t restricted to just one African country. In this oral history interview, Marlyn Butchins, a quilting artist who grew up in Bulawayo, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), describes Jewish life in Bulawayo during her childhood and her family’s participation in synagogue services and Jewish rituals.

Worldwide Enterprise

Yiddish publishing was never exactly easy. It has faced government censorship, political upheaval, diaspora and a geographically fragmented market, weak educational institutions, the temptations of assimilation, state-sponsored repression, and the overwhelming catastrophe of World War II. Nevertheless, writes Zachary Baker, some things did go right: Yiddish-speaking Jews were readers. They were by and large an urban (or urbanizing) population. And their geographical dispersion eventually helped make Yiddish book publishing a viable worldwide enterprise.