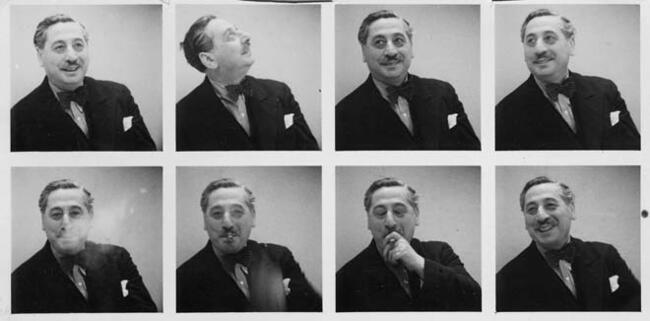

Weekly Reader Sholem Asch

November 7, 2021

For some aspiring writers, the beginning of November is the beginning of National Novel Writing Month, or NaNoWriMo, in which participants try to write an entire novel in, well, one month. For most, the purpose is really to make the attempt rather than to actually complete a novel in such a ludicrously short length of time. But if there was one Yiddish writer who might have been able to achieve that goal, it’s the one who was fittingly born right on November 1: Sholem Asch. Famously prolific, popular, and controversial, Asch was a writer who appealed both to the literati (sometimes) and to a mass readership, and he was one of the first Yiddish writers to reach a large audience in translation. So if you’re trying to write a whole novel this month, or know someone who is, you might look to Asch for inspiration.

—Ezra Glinter

Always Available

If you’re looking for Asch’s books, they are, fortunately, not rare. Our Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library has a huge selection available for reading and download, and if you want to a copy to hold in your hands, we can help with that. Not surprisingly, Asch was one of the authors selected for inclusion in the Sami Rohr Library of Recorded Jewish Books, a collection of Yiddish works read and recorded at Montreal’s Jewish Public Library in the 1980s and ’90s. Ironically, it’s some of the English translations, now rather dated and out of print, that are harder to get hold of.

Listen to Asch’s Onkl Mozes, read aloud by Vove Vaynshtayn

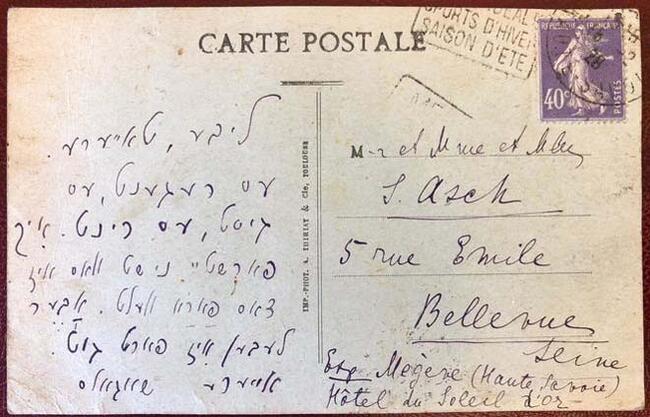

A Postcard from Chagall

As one of the most popular Jewish writers of his time, Asch maintained contact with many of his artistic peers—some of them friendly, some less so. His relationship with Marc Chagall was mostly friendly—the two families moved to Paris around the same time in the 1920s, and Chagall painted portraits of both Asch and his wife, Madzhe. The Chagalls also wrote regular postcards to the Asch family, including this light-hearted number, sent from a fashionable ski resort in the Alps.

Read a postcard from Chagall to Asch

Asch in Translation

The fact that Asch was one of the first Yiddish writers to reach a broad audience was no accident. Asch himself understood that Yiddish literature—and his own work in particular—would only receive the attention it deserved once it could be read by non-Yiddish-speaking readers. To that end he took a proactive approach to his translations, beginning by pressing his own father-in-law, an autodidact with a passion for languages, into service. Nonetheless, Asch’s relationship with his translators wasn’t always an easy one.

Read about Asch and his translators

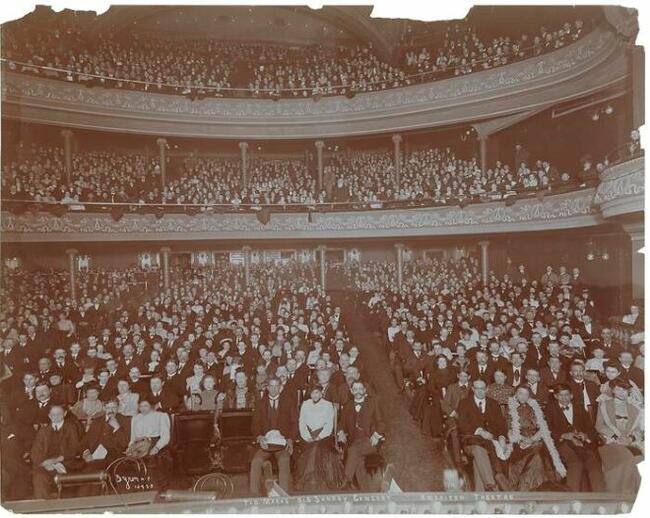

Asch Onstage

Sholem Asch could be thought of as Yiddish literature’s first modern celebrity, almost a one-man global brand. The obscenity trial surrounding his play Got fun nekome (God of Vengeance), as well as its frank depiction of two women in love, inspired Paula Vogel’s recent Broadway hit Indecent—but Asch wrote over twenty more plays exploring interfaith love, the Jewish underworld, Messianic dreams, and class and power in the Jewish world.

Listen to a lecture series on Asch and the Yiddish theater

Asch Excommunicated

The greatest controversy of Asch’s career came in 1939, when he published The Nazarene, the first of a trilogy of novels about the life of Jesus Christ. The novel was hugely popular, staying on the New York Times bestseller list for months and selling two million copies in two years. But it was less warmly received among Asch’s Yiddish readers, and unlike the rest of his work, appeared in Yiddish only after it was published in English. Leading the attack on Asch was the Forverts newspaper, where Asch had long published, and its irascible editor Abraham Cahan. Cahan even wrote a book-length treatise attacking Asch for his seeming betrayal of Judaism on behalf of Christianity—a charge that Asch denied.