Painted from Memory: Saul Raskin and the Question of Jewish Art

Critics and scholars (and Yiddish Book Center fellows) often talk about Yiddish writers—but what about Yiddish artists? Can we attach language or culture to the visual arts and the visual artist? This is a question that the multitalented, multimedia artist and art critic Saul Raskin might ask, and if there are indeed Yiddish visual artists, he himself surely qualifies.

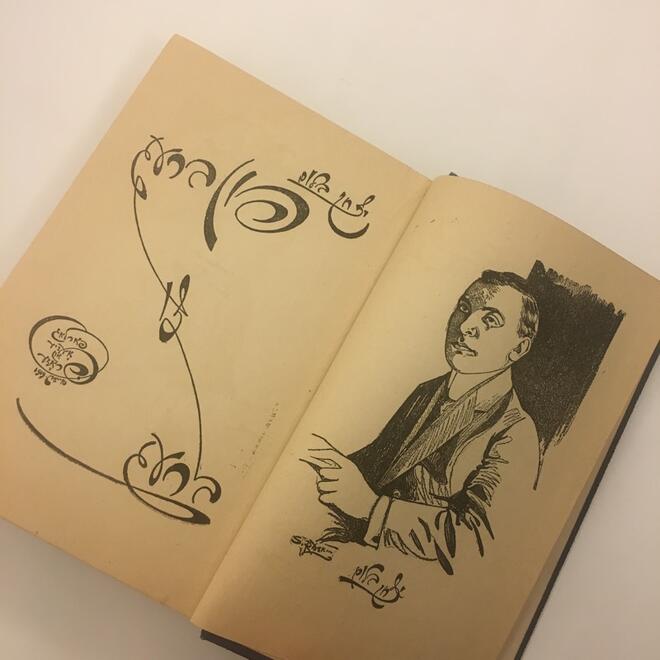

Raskin’s work is ubiquitous: he wrote travelogues, art books, and even a mystical novel, the evocatively titled An oysgetrakhter emes (An Invented Truth). Many other books bear his mark in some form: his typography adorns their covers, his illustrations add life to their pages.

Raskin was born in Nogaisk (now known as Prymorsk, in southern Ukraine) in the Russian Empire in 1878. As a young man, he studied lithography, painting, and drawing at art schools in Odessa, Berlin, Paris, and beyond before immigrating to the United States in 1904.

He made wide-ranging contributions to New York’s Yiddish culture circles: as an educator, critic, and artist. Raskin took a populist approach to art, striving to make it accessible to the public; he gave museum tours and art lectures for the left-wing Yiddish culture organization Der arbeter ring (The Workmen’s Circle). He worked for a time as the art director of the 92nd Street Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association (now the 92nd Street Y). He became active in the Yiddish press and literary scene: one of the first art critics to write in Yiddish, he contributed criticism about art and theater to several prominent Yiddish journals and newspapers, such as Tsaytgayst, Der tog, Fraye arbeter stime, Tsukunft, Chaim Zhitlovsky’s Dos naye lebn, and Avrom Reyzen’s Dos naye land. Zalman Reyzen (Avrom’s brother) wrote of him, “One of the best Yiddish art writers, his style, both in writing and in painting, is realistic with impressionistic and decorative inclinations.”

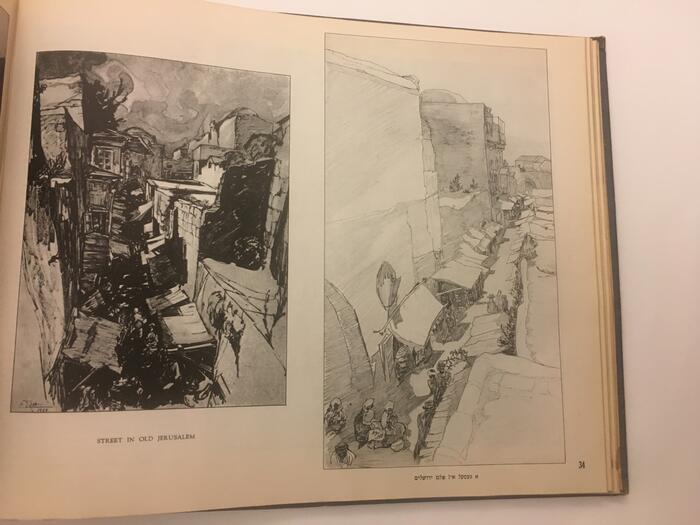

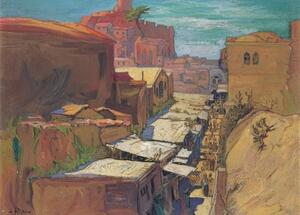

As a critic, he was interested in what made “Jewish art” Jewish. When it came to this question, however, he asked it not just with the distance of a critic; it was paramount to his work as a visual artist. "I am an artist and I am a Jew, but first and above all, I am a Jewish artist, for Jewishness is the source, the centrality, the essence of my art, as it is the essence of my being,” he wrote late in life. His work frequently represented Jewish life, Jewish liturgy, and Jewish space, ranging from oil paintings of shul scenes and holiday observances to engravings based on Pirke Avot.

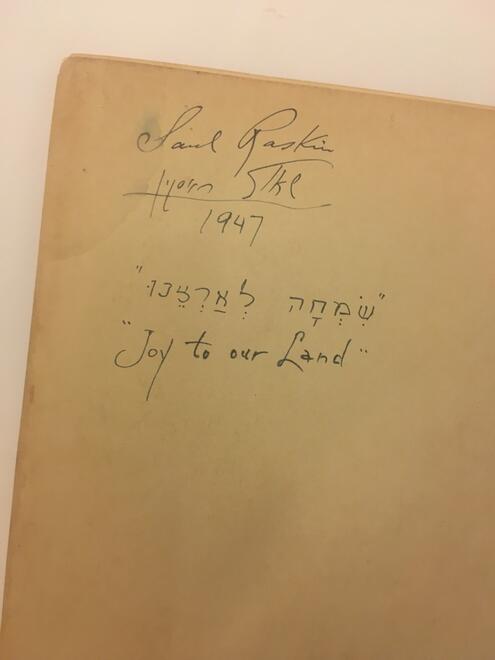

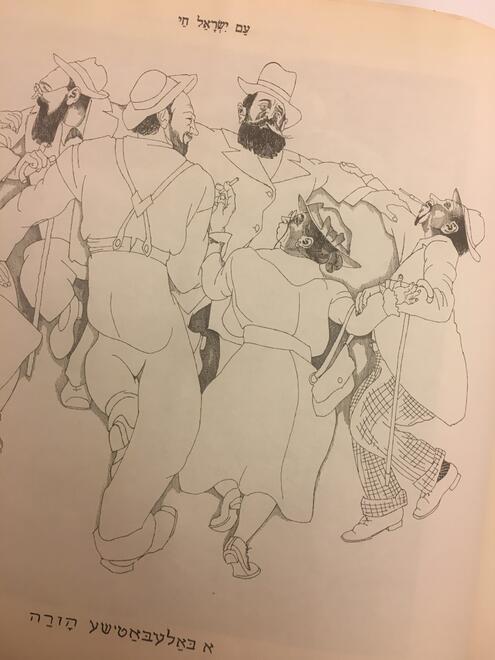

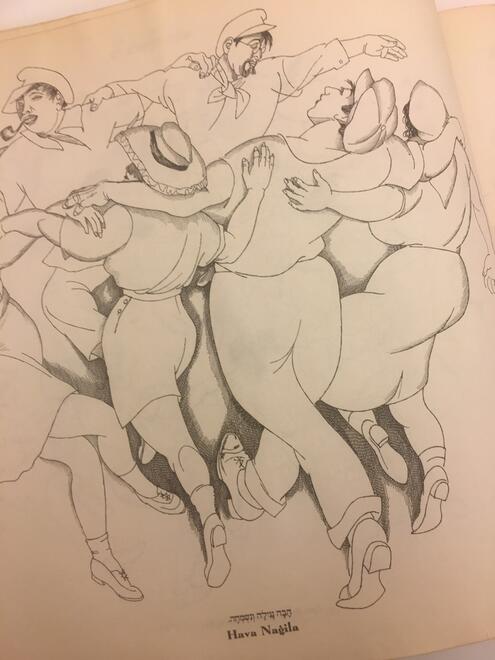

He became an ardent Zionist, which is reflected in a fascinating book from our collection: his 1947 large-format art book, bilingually titled Land of Palestine and Artzeinu v’ameinu (Our Land and Our People). In the introduction, Raskin describes the book as “my thanksgiving to Eretz Israel for the part she played in my life.” The book showcases his technical and thematic range, featuring hundreds of his drawings, engravings, and paintings of landscapes, religious scenes, the Yishuv, and everyday life in erets Yisroel, as well as his writing, in Yiddish, about his experiences of the place. Our copy bears a special inscription from the year of its publication: it is signed by Raskin himself, his name in both Yiddish and English, with the Hebrew words “simcha l’artzeinu” (“joy to our land”) underneath. “Simcha l’artzeinu” is also the title of the book’s final section, which features multiple drawings and paintings depicting group dances: an exuberant celebration of the Zionist dream. (Although he visited Palestine five times, and it had an immense effect on his art and writing, he never emigrated there.)

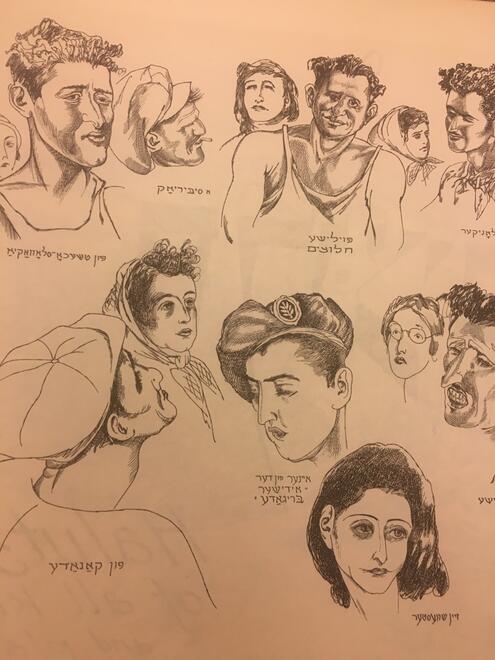

Some images are labeled in Yiddish, some in English, some in Hebrew; some artworks have words of these languages built into the images. Scenes from a growing modern Hebrew culture are captioned in Yiddish. As Raskin himself explains in the book’s English introduction, “The three languages used, Yiddish, Hebrew and English are also due to the different times and circumstances I lived through. There is no consistency in the order in which the three languages are used—it just happened that way.” (Notably, however, Yiddish is absent from the book’s title.) The book is a work of art unto itself, thoughtfully designed to reflect a Yiddish-speaking American Jew’s yearning for Zion—at a crucial moment for political Zionism, no less.

Much is lost, unfortunately, in reproducing his paintings in black-and-white; the worlds he rendered in oil paint are lush with color, dreamlike in their depiction of images at once familiar and unfamiliar. His painting style is decidedly modern; while still representational, it leaves behind the stricter formal conventions of 19th century realism, utilizing bold color and radically cropped perspective. Raskin’s is a more fluid approach that recalls the Expressionist and post-Impressionist styles of painters like Cezanne, Matisse, Van Gogh, and Modigliani, but that is nonetheless all his own.

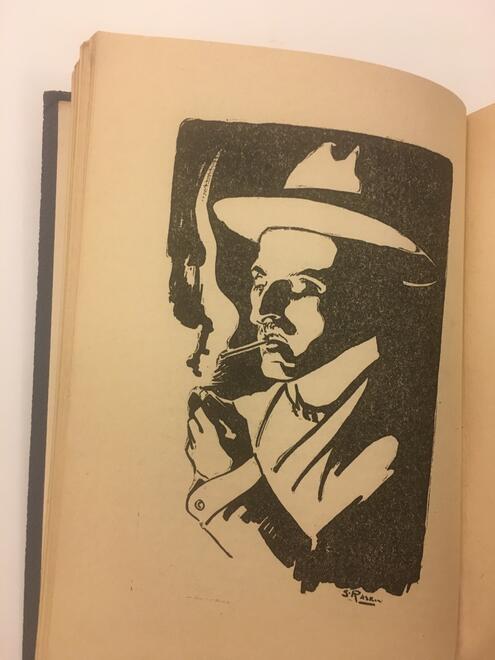

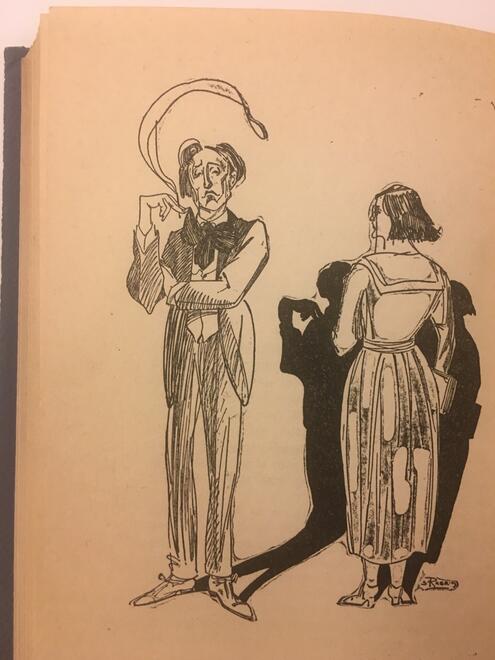

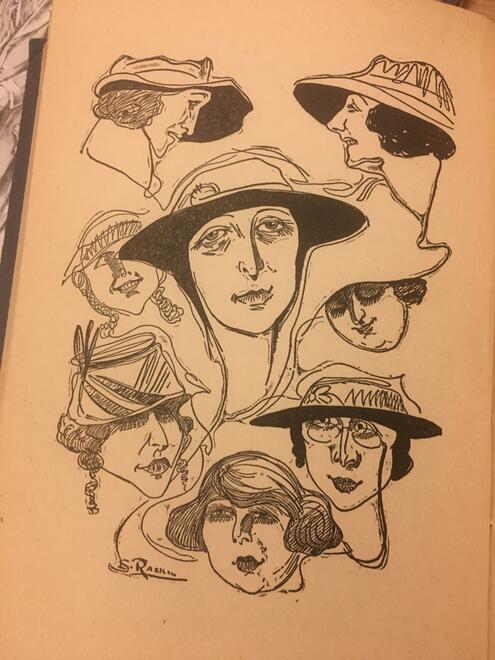

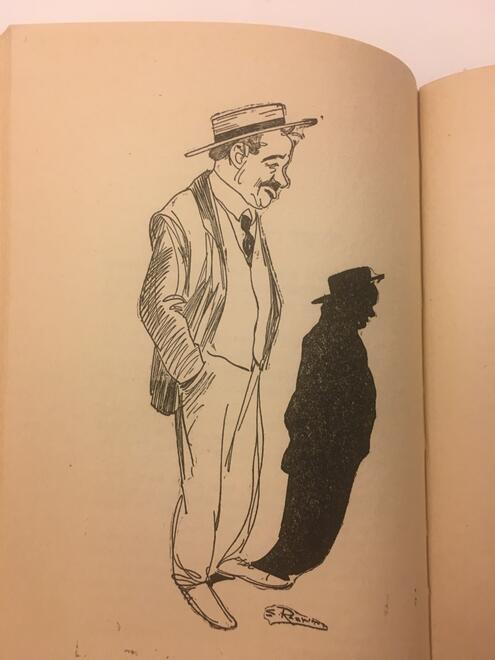

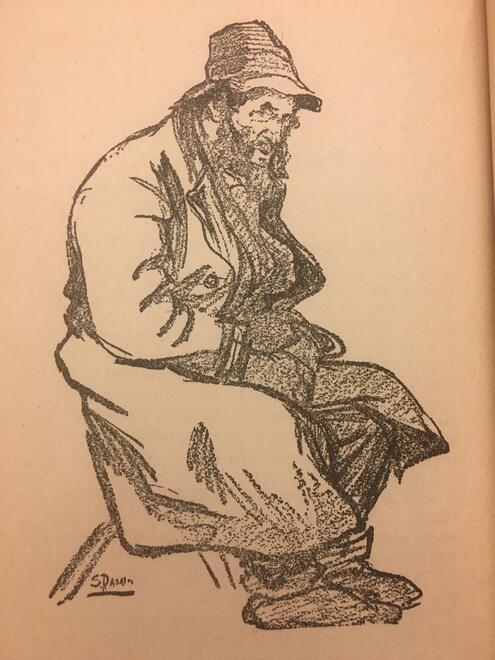

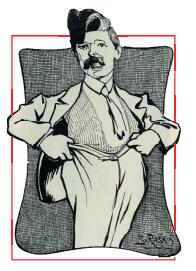

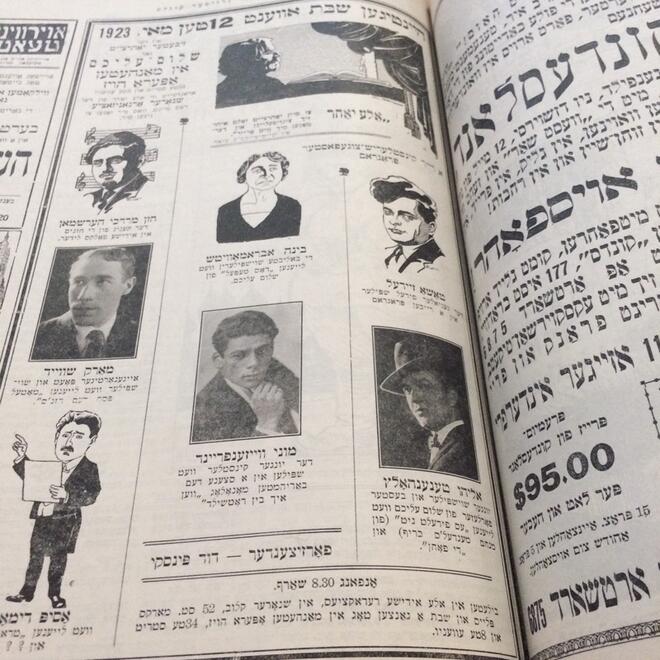

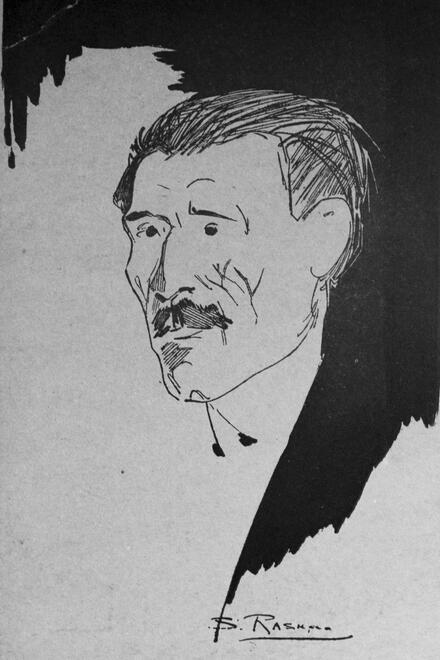

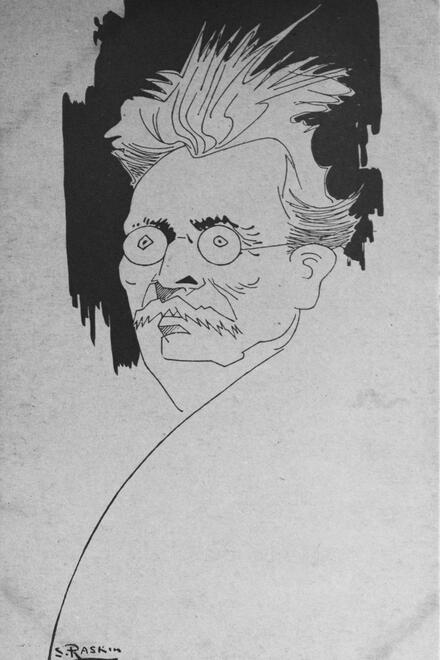

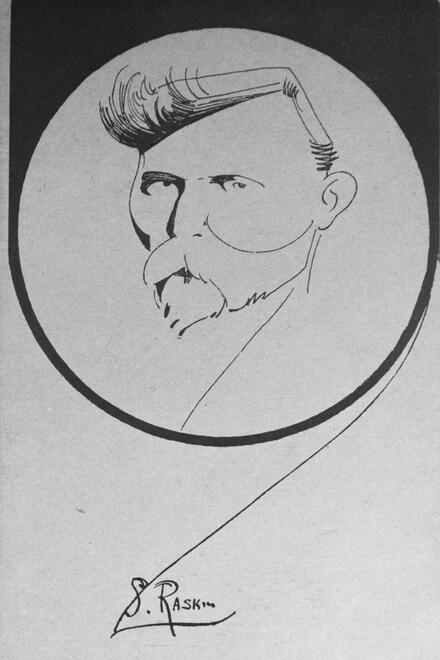

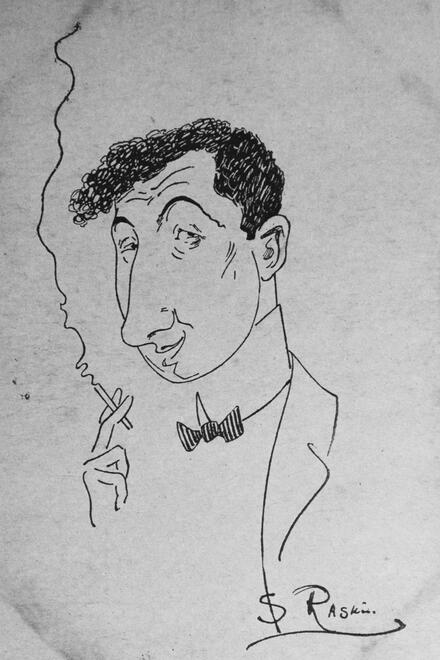

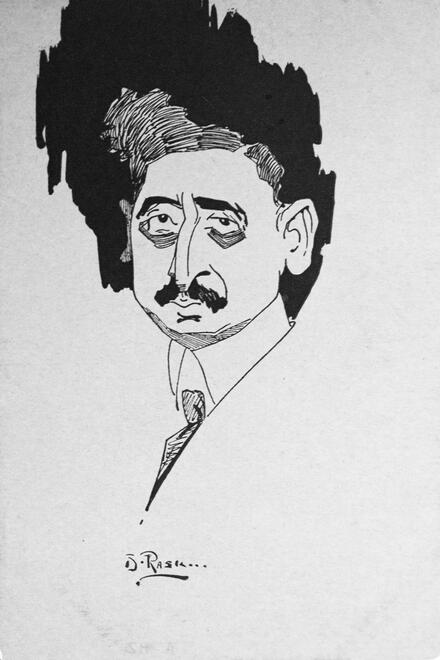

His characteristic caricature is particularly recognizable, and once I learned about Raskin, I began to see his work everywhere. For years, he drew caricatures of political and literary personages for the satirical weekly Der groyser kundes, of which we recently received a donation of bound volumes. Originally called Der kibitzer when it was founded in 1908 by notorious humorist Joseph Tunkel (known as Der Tunkeler), it changed its name to Der groyser kundes (The Big Stick or The Big Prankster) when Jacob Marinoff took the helm a year later. Just as “no one was safe from the poison pen of Yoysf Tunkl,” as Eddy Portnoy recently wrote for his Handpicked selections from the Yiddish Book Center's collection, nothing was above the pranks of Der groyser kundes. And Saul Raskin was the paper’s resident visual prankster. He depicted his subjects in minimalist caricature, utilizing bold lines and exaggerating their features; for instance, they are often drawn with elongated noses that form a continuous line up to their brows.

For a lover of Yiddish culture, Raskin’s caricatures of Yiddish writers are particularly enjoyable. I was introduced to these through a set of curious postcards. Most likely sent to us in a box of books (as much of the ephemera in our collection tends to be), they turned up in our building years ago, and surprised and delighted me with their stylized portrayals of many of the great Yiddish writers and cultural luminaries: Avrom Reyzen, Sholem Asch, Chaim Zhitlovsky. It was natural for Raskin to draw modern Yiddish writers, just as it was natural for Picasso to paint Gertrude Stein (and indeed, some of Raskin’s writer drawings even bear resemblance stylistically to that portrait). Just as Picasso was part of a circle of expat modernist artists and writers at Stein’s salon in Paris, Raskin’s social environment in New York was populated with Yiddish writers. He strove to inhabit his cultural moment through visual art; they did so through literature.

An obituary published by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on the occasion of Raskin’s death in 1966 memorializes him by way of his “sketches of New England fisherman” and “pushcart peddlers on the Lower East Side.” Such a tribute is revealing: his subject matter was both quintessentially American and quintessentially American Jewish. But his milieu was firmly Yiddish.

—Miranda Cooper