Together in Mournful Protest

The long lineage of Jewish funeral marches lives on in this piece of Yiddish sheet music

Published on April 11, 2024.

In response to crises from the Jewish world and beyond, American Jews return time and time again to a form of protest that marries mourning rituals with political mobilization: the troyer-marsh, or funeral march. For decades, these funeral marches have fueled Jewish communities with spiritual strength as they’ve fought for workers rights, minority rights, and human rights.

Looking back, we can find an early example immediately after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911, when Jewish workers and others responded to the deaths of 146 garment workers, almost all women, by protesting in mourning garb in New York City. In 1943, the “We Will Never Die” protest pageant brought tens of thousands of Jews together across the country to mourn the millions lost to Hitler’s genocidal campaign and to militarize those willing to fight the Nazi foe. In 1987, hundreds of thousands of Jews marched on Washington to demonstrate support for Soviet Jewry, many observing a fast in solidarity with the plight of the refuseniks.

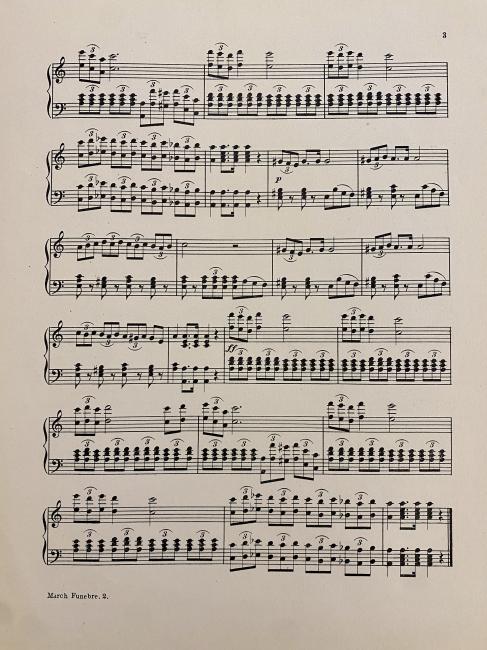

Together, all of these protests reflect the long legacy of troyer-marshn in the United States. This piece of sheet music, “Der yidisher troyer-marsh” (“The Jewish Funeral March”), commemorates one of the very first troyer-marshn of the twentieth century. Now highlighted in our core exhibition, Yiddish: A Global Culture, the sheet music offers a glimpse into the lineage of historical Yiddish protest.

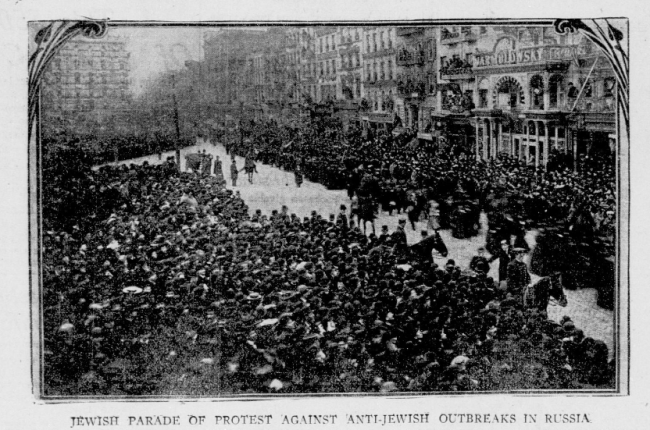

The music commemorates the troyer-marsh of December 5, 1905, when an estimated 125,000 to 250,000 Jews marched through New York in mournful protest against the recent wave of Russian pogroms. This particular protest was spurred by the latest and most deadly pogrom in Odessa, in which over 400 Jews were murdered between October 18 and 22. The Jewish Defense Association organized the march, and over ninety-five organizations attended, including an organization of pogrom survivors from Kishinev, a volunteer military organization called the Zion Guards, and the Manhattan Rifles, another Jewish military organization. Jews from trade unions, political groups, social clubs, professional organizations, and musical unions attended, creating a great mass of humanity that prompted surveillance by 1,300 policemen.

They began at Rutgers Square mid-day, led by the Jewish Theatrical Musical Union’s fifty-piece band playing Chopin’s “Funeral March.” As they continued down East Broadway, the English-language press reported that the Choristers Union, the Boy Synagogue Union, and the Downtown Cantors Association continued the musical procession. Visibly grieving crowds met the paraders as they walked on. The procession stopped at at least three synagogues on Norfolk and Rivington to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish. One newspaper captured their sorrowful sound: “Occasionally, at a concerted signal, the bands would stop playing. Then above the murmur of the moving throng would arise, softly at first, then swelling to full tone, the voices of the synagogue boy choirs in a hymn for the peace of the dead. Then the voices would gradually die away in silence.”

The day was reserved for tragedy. No business was conducted in the Lower East Side, as the day had been set aside for fasting and prayer. Mourning residents draped tenements and businesses in black cloth inscribed with “We mourn our loss” and “Reverence for our murdered brethren.” Like the buildings, the processioners donned funeral wear, crepe bands around their arms, and black hats appropriate for the solemn gathering. The Forverts described the scene: “Der kvartal ayngevikelt in troyer” (“The neighborhood was wrapped in sorrow”).

In the fashion of mournful protest, some wore buttons bearing the American flag overlaid with the “flag of Zion.” Even the Yiddish presses printed black borders around their coverage of the Odessa massacres, symbolizing the loss of life.

As the masses marched from Fourth Street to Union Square, all business halted for about two hours. When they reached Broadway, the police stopped vehicular traffic to allow their passage. The “greatest throngs” of mourners gathered in Union Square, where Russian-Jewish labor leader Joseph Barondess read aloud a list of resolutions denouncing the Russian massacres and calling upon all Jews to rally in protest against such acts. The resolutions were met with resounding affirmation by the crowd.

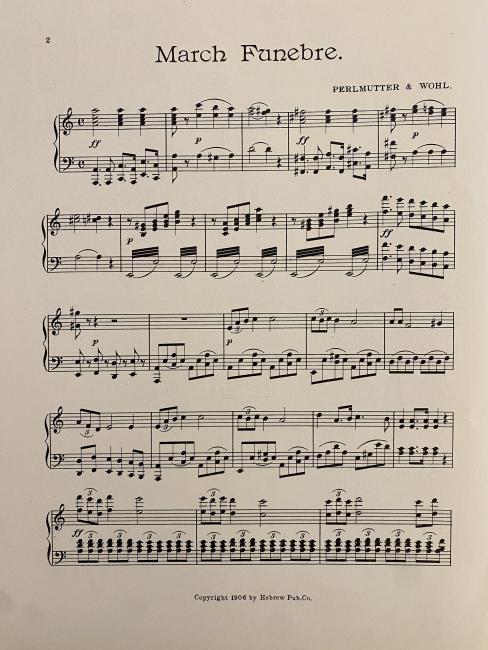

In honor of this monumental mobilization, long-time collaborators and musical composers Arnold Perlmutter and Herman Wohl published this funeral march composition. Written specifically for the occasion, this 1907 version of the music was printed by the Hebrew Publishing Company with art by Louis Terr. Today, a sole copy of the sheet music rests in our collection. While the act of protest is ephemeral, artifacts like this one preserve such potent political moments for future generations.

— Maya (Zuni) González, 2023–2024 Harriett and Seymour Shapiro Fellow

This post is one of a series expanding on books and artifacts found in our core exhibition, Yiddish: A Global Culture. Read more:

Further Reading:

English press coverage of the march in the The New York Times, December 5, 1905

Yiddish press coverage of the march in Di varheyt, December 5, 1905