Weekly Reader: Celebrating National Poetry Month with Yiddish

It’s April, and you know what that means. If you were about to say “the cruelest month,” as T. S. Eliot put it in The Waste Land, you’re close. April is National Poetry Month! For many of us, however, poetry isn’t always the easiest thing to read, even in our native tongue. (Here’s looking at you, Eliot.) The language can be difficult, and the content can be both allusive and elusive. Which makes reading poetry in a second language, as Yiddish often is, all the more difficult. Fortunately, we have not only many translations of Yiddish poetry but side-by-side translations as well, which can help readers appreciate the poems as fully as possible. Here are some great examples of Yiddish poetry from our collections, with English alongside.

—Ezra Glinter, Senior Staff Writer and Editor

I Have Seen

Rosa Nevadovska (1890–1971), a poet from Białystok, immigrated to the United States in 1928. She was married briefly and gave birth to a daughter, who died at the age of two during a winter in Moscow, where the poet lived from 1914 until the end of World War I. In the United States, Nevadovska was a writer and journalist, traveling, lecturing, and residing in various cities, from New York to Venice, California. She published one volume of poems in her lifetime, Azoy vi ikh bin (As I Am), in 1936. After her death, her family discovered scores of unpublished poems, which were published as Lider mayne (My Poetry) in 1974. “I Have Seen,” translated by Merle Bachman, former Yiddish Book Center translation fellow, appears in this volume.

Read Rosa Nevadovska’s work in the Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library

Blossom in Ashes

Rivka Basman Ben-Haim, who passed away in March 2023, spoke sparingly of the horror-filled years of the Holocaust. But in 2020, just a few years before her death, she published Bliung in ash (Blossom in Ashes), which addresses her experiences in those years. Here are two selections from that collection, translated by Zelda Kahan Newman.

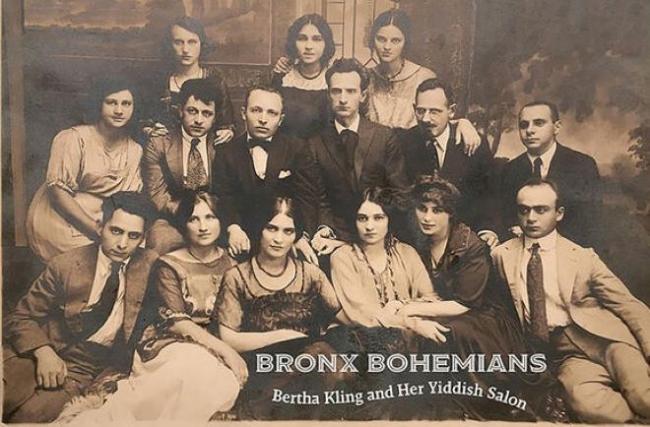

Bronx Bohemians

Readers of our website will no doubt have had an opportunity to visit our Bronx Bohemians blog, which explores the fascinating circle of Yiddish writers and artists surrounding Yiddish poet Bertha Kling and her husband Yekhiel. Although many members of Kling’s salon have had their work translated into many languages, Bertha Kling’s own poetry has remained largely untranslated. Here, however, are a few of Kling’s own poems, translated by Weaver and read aloud by several performers.

Circular Landscapes

Debora Vogel (1902–42) was a Polish Yiddish writer of poetry, short stories, and literary and art criticism. Associated with the Yiddish avant-garde, she published two books of poetry and a book of short sketches. Vogel termed her style “white words” and aimed “to create a new lyric poetry of the urban condition . . . in which monotone becomes theme.” In poems such as “Circular Landscapes” she collapses the dualities between interior and exterior spaces and between domestic and urban landscapes.

Read “Circular Landscapes,” translated by Anna Torres

Buy Montage, a collection of Fogel’s work translated by Anastasiya Lyubas

Does It Mean I Long for You?

Malka Locker was born in 1887 in Kitev, Galicia (present-day Ukraine). In 1910, she married her cousin Berl Locker, who became a Zionist leader, and traveled with him to cities around the world. Locker did not begin writing poetry until the age of forty-two, when a friend who was impressed by the poetic quality of her letters suggested that she try. This poem is from Locker’s second poetry collection, Du (You). The book’s epigraph—“Where can I find You / And where can I not find You?”—is taken from Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev’s song/prayer “A dudele” and highlights the book’s theme: the love that inhabits the blurry borderland between eros and prayer.

Read “Does It Mean I Long for You?,” translated by Ri Turner