Weekly Reader: Pseudonyms in Great Yiddish Literature

What’s in a name? For some authors, the answer can be quite a lot. Pseudonyms have always been common in the literary world, although the reasons for them vary. In some cases they conceal the author’s gender, as they did for George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) and George Sand (Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil). In other cases they’re simply more marketable. Anne Rice, the popular vampire novelist, was actually Howard Allen Frances O’Brien. And often they’re used to preserve an author’s reputation when they decide to dip into less prestigious genres, usually for financial gain. Yiddish writers used pseudonyms too, sometimes more than one and for a variety of reasons. It was often the most important and illustrious Yiddish authors who went by a nom de plume. Why? Let’s find out.

—Ezra Glinter, Senior Staff Writer and Editor

How Do You Do?

It was no secret that “Sholem Aleichem” was a pseudonym. No one, after all, is actually named “How Do You Do?” Why Sholem Rabinovitz decided to use this rather absurd moniker is a mystery that literary critics still argue over, and the name trips up writers and bibliographers less familiar with Yiddish. (You cannot call him, for example, “Mr. Aleichem”—at least not with a straight face.) Nonetheless, Sholem Aleichem became the most popular and influential Yiddish writer of all, and that’s the name by which he will always be remembered.

Read about Sholem Aleichem, the quintessential Yiddish writer

The Bookseller

Part of Sholem Aleichem’s motivation for using a pseudonym might have been the precedent set by Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh, often considered the grandfather of modern Yiddish literature. Abramovitsh chose to go by “Mendele Moykher-Sforim,” meaning “Mendele the bookseller”—as folksy as “Sholem Aleichem” and just as obviously not a real name. While you can abbreviate it to “Mendele,” “Mr. Sforim” is a no-go. Taken together, Rabinovitz’s and Abramovitsh’s use of pseudonyms means that two out of the three classic Yiddish writers (the third being I. L. Peretz) are almost never referred to by their real names.

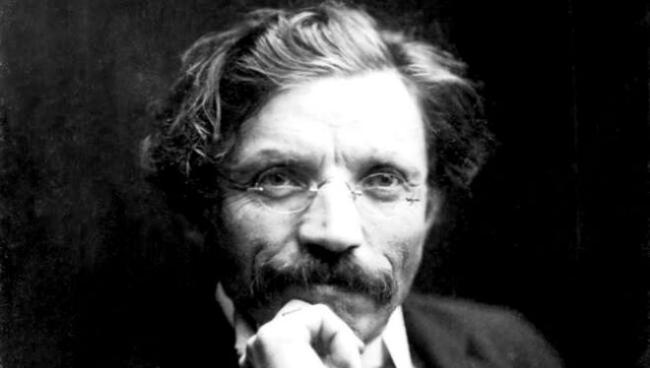

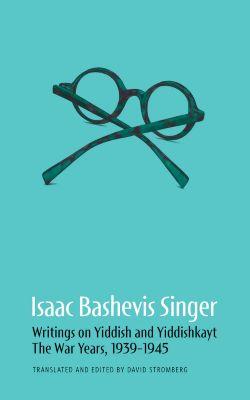

Batsheva’s Son

One of the great bits of Yiddish literary trivia is that the most successful Yiddish writer of the twentieth century, Isaac Bashevis Singer, also used a pseudonym. In English he used all three names, but in Yiddish he generally went by Isaac Bashevis, and Bashevis wasn’t his given name. It was a matronymic taken from his mother’s name, Batsheva or Bassheva. And that was only for his literary work. For his copious journalism he went by either Yitskhok Varshavski or the more mysterious D. Segal. While that side of Singer’s literary career has been largely overlooked, some of his pseudonymous journalism has recently been collected and translated by David Stromberg in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt: The War Years, 1939–1945, published by the Center’s imprint, White Goat Press.

Read an annotated guide to the work of Isaac Bashevis Singer

Buy Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt: The War Years, 1939–1945

Tree of Life

It wasn’t just male writers who used pseudonyms. And the Yiddish women who wrote pseudonymously weren’t necessarily trying to disguise their gender. One of the most celebrated Yiddish poets of the twentieth century, Anna Margolin, was in fact named Rosa Harning Lebensboym, and she worked as an editor under her real name. She also used several other pseudonyms for her journalism, including “Sofia Brandt” and “Clara Levin.”

Read “During Sleepless Nights,” a story by Anna Margolin published under the name “Khave Gross.”

Courtyard Bard

The pseudonymous Mimi Pinzón, one of the most significant Argentinian Yiddish writers of the twentieth century, renamed herself after a Parisian seamstress in a story by French romantic writer Alfred de Musset. Pinzón—best known for her novel Der hoyf on fenster (The Courtyard without Windows), which depicts the world of Buenos Aires conventillos, or tenements—also translated copiously between Spanish and Yiddish (she translated Borges into Yiddish, for example) and worked in the South American Yiddish press, sometimes under additional pseudonyms and sometimes under her real name, Adela Weinstein-Shliapochnik.

Read Der hoyf on fenster in the Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library

Read a selection from Der hoyf on fenster in English, translated by Jonah Lubin