Q&A with Christa Whitney on a Decade of the Wexler Oral History Project

Reflecting on a Decade of Story Collecting

Executive Director Susan Bronson talks to director of the Yiddish Book Center’s Wexler Oral History Project, Christa Whitney, about a decade of oral history at the Yiddish Book Center.

Susan Bronson: Tell me a little bit about the genesis of this initiative? How did it begin and what do you see as the biggest milestones in its development over the last decade?

Christa P. Whitney: The idea of an oral history project had actually been around in the past. Back in the early years of the Yiddish Book Center when Aaron Lansky and others were out collecting Yiddish books, they also were hearing amazing stories during their travels. (Some of those stories made their way into Aaron's book, Outwitting History.) But in 2009, when I arrived at the Center as a fellow, the idea surfaced again among other ideas of how to expand the Yiddish Book Center's mission beyond the Yiddish book collection into other areas of Yiddish and modern Yiddish culture. So we convened a group of people who were on staff at the time to discuss the idea. We were trained by the experienced oral historian Jayne Guberman (formerly of the Jewish Women's Archive), and then we piloted the idea, beginning to interview people onsite in Amherst. We immediately began hearing incredible stories and saw the value in recording them. Over time, we focused in on specific topics related to Yiddish language and culture, interviewing scholars and performers of klezmer music and Yiddish theater as well as many native Yiddish speakers and others.

One early milestone was when we began to take the recording on the road. While we love our local community in western Massachusetts, we soon realized that limiting ourselves to people who were able to travel to us was not going to yield a collection that was very representative of Yiddish language and culture. So as soon as December 2010, we began interviewing at conferences and festivals. We later developed a model of fieldwork where we worked with local connections or a local partner organization to set up interviews with Yiddish speakers in communities far and wide, allowing us to collect stories from all over the world.

Other milestones were when we recorded our 100th, then 500th, and, in 2019, our 1000th interviews. When we started out, we never imagined we would reach those numbers!

SB: What makes this collection unique and important?

CPW: For a variety of linguistic, ideological, and political reasons, Yiddish resources have not always been accessible. The Yiddish Book Center has always had a focus on making more materials accessible, and our oral history project follows that model. A majority of the interviews we’ve collected are available in full on our website, something that puts these new primary sources out there for researchers and the public. That is not always the case with other archives and oral history projects, but that was something we really prioritized from the beginning—making the materials accessible.

And the interviews themselves chronicle shifts in the place of Yiddish language and culture over the twentieth century and into the first two decades of the twenty-first century. The elders we've interviewed have firsthand accounts of Jewish life in Eastern Europe and elsewhere in the world in the 1920s and '30s, which are valuable historical documents. On the other end of the spectrum, some of the younger people we've interviewed talk about what relevance Yiddish has to them now. Even in the past decade since we've been recording interviews, we've seen shifts and developments in the way Yiddish is understood in broader culture. Those shifts are documented in the collection.

SB: I personally find some of your international interviews to be especially compelling—in part because they provide insight into Yiddish communities and histories that I had not known existed. What are one or two interviews from your world travels that are particularly meaningful, important, or surprising?

CPW: This has certainly been a very exciting aspect of the work. It's always hard to pick individual examples, but there are a few that come to mind that represent surprising moments of deep learning for me personally. One was an interview I did in Finland a couple years ago. I was there to present as part of the International Oral History Association conference, and—as I always do now wherever I travel—I looked up local Yiddish speakers I might connect with and interview while there. Through that research, I learned about the unique history of the Jewish community in Finland, one of the few Jewish communities that remained intact through World War Two because of the political situation of Finland during the war. Because of the Soviet Union’s attempt to annex Finnish territory after the Molotov-Rippentrop Pact and various other complex socio-political reasons, Finland was allied with Nazi Germany for much of the war, meaning Germans fought alongside Finnish soldiers. And because Finland had universal male conscription into its army, this meant Jewish soldiers were fighting alongside Nazi-German soldiers. I interviewed one veteran who was drafted toward the end of the war, but who experienced this firsthand. As a Yiddish speaker, he was even brought in to help translate between German and Finnish military officials. When he was brought into a room where the officials were heiling Hitler, he thought he was done for. But he survived and through that interview I learned about that fascinating and peculiar history, as well as about the history of the Jewish community in Finland, which I didn't know much about before.

Another interview that stands out is one I did in Tel Aviv with Lea Szlanger. She was born in Kalisz, Poland, and had a quite successful career there after World War Two. She was involved in Ida Kaminska's Yiddish theater in Warsaw and was a bit of a star in that theater scene. But at a certain point, she and her family decided to make aliyah to Israel. Lea was reluctant to leave. She describes this incredible moment of arriving in Israel in high heels and stepping out onto the sand and her heels sinking into the sand. This was a powerful metaphor of her disappointment upon arriving in a new nation where she would have to start again building a new life. She ended up connecting with Yiddish actors in Israel (including the famous Joseph Buloff, Shimon Dzigan, and Yisroel Schumacher) and creating a career for herself there, but it was a difficult transition. That interview and others I did with Yiddish speakers and activists in Israel gave me a deeper understanding of the difficulties Yiddish culture faced as Israel established itself and developed a new national Jewish culture that centered Hebrew and actively suppressed Yiddish by limiting how Yiddish actors could work and how Yiddish newspapers could be published, for example.

SB: One of the most poignant aspects of your work is that you often interview elders in their final years and even days. What is one example of such an interview, and what was its impact on you?

CPW: Well, a pretty recent example that comes to mind is the interview I did in September 2019 with Harold Bloom. I grew up with a mother who is a trained librarian and a father who was an English major at Yale, both big Shakespeare fans, so Harold Bloom's books were around my house growing up. And because my family includes a long line of Yale alumni, I was familiar with Bloom's stature as a critic and thinker in the realm of English literature. But I didn't know much about his Jewish background or identity. So I was thrilled when he agreed to be interviewed. I was pretty nervous as I walked down the block from my aunt and uncle's house in New Haven to his. But he was open and welcoming, and eager to talk about his Jewish background, including the difficulties he faced as a young Jewish scholar in an elite university that was rife with anti-Semitism. The interview itself was fascinating, revealing that, while he hadn't written much about it, he was a big fan of Yiddish literature. In fact, at the time, he was working on a new piece of writing about Dante and told me how he had revisited the Yiddish translations of Dante as part of that project. The fact that he held Yiddish in such high esteem but hadn't written much about it raised a lot of questions for me. But he had limited endurance because of his health, so the interview was relatively short, leaving some of those questions unanswered. When I left, he looked me straight in the eye and said he hoped to see me again to talk further. And because I do often visit my family in New Haven, I looked forward to that opportunity. But just a few weeks later, he was dead. It made me so grateful for that chance, the honor to be the last person to do a recorded interview with him, but also of course very sad that there wasn't that chance to meet again and follow up.

SB: I think that is a critical part of this project—capturing voices and stories that would otherwise be lost and preserving them for generations to come. My final question: as we mark the project's tenth anniversary and celebrate all that you and your team have accomplished, what lies ahead?

CPW: There are still so many people to interview! We have lists of names that we are working through and to which we add regularly as we get recommendations and make new connections. I think the priority is still in collecting the stories. Though the generation is shifting, there are still people out there who are native Yiddish speakers in their 80s and 90s who have a lot to share with us about what life was like back when Yiddish was spoken more broadly, when there were multiple Yiddish newspapers and Yiddish theater groups in major cities around the world. At this juncture, we are also doing some meta-analysis of our work to date—taking stock of what parts of the history of Yiddish culture in the last 75 years are not as well represented in our collection and trying to fill in those gaps. And there is of course plenty of work to do just getting the interviews processed and indexed and accessible to the public. So that will certainly keep us busy.

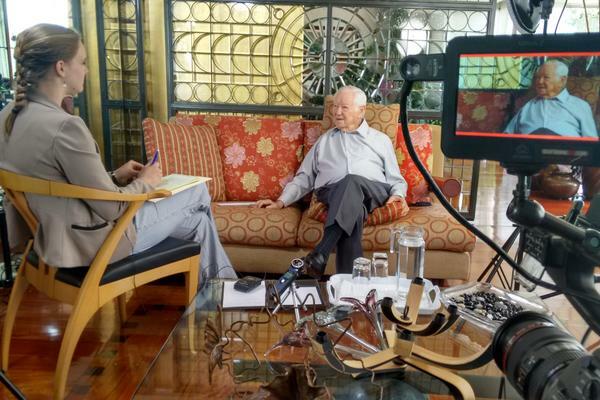

Photo of Christa Whitney preparing for an interview in April 2018 by Heather Daniels Pusey.