Peretz Markish and His Circle

By Abraham Sutzkever, Translated by Justin Cammy

After their escape from the Vilna ghetto on September 12, 1943, Yiddish poet Abraham Sutzkever and his wife Freydke spent six months in the forest among partisan fighters before they were airlifted and brought to safety in Moscow. There, Sutzkever was conscripted by the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee to write a chronicle of his two years in the ghetto. Sutzkever’s time in Moscow put him into contact with leading figures of Soviet-Yiddish culture. Years later, once he had firmly re-established himself in Tel Aviv, he penned several reminiscences of his friendships in Moscow, including essays on Yiddish poet Peretz Markish, director of the Moscow State Yiddish Theater Shloyme Mikhoels, and the great Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg. These essays provide critical information about how Sutzkever navigated the complicated political atmosphere in the Soviet capital, and his affection for those who welcomed him there—many of whom had suffered repression, imprisonment, and death at the hands of the Stalinist regime by the time Sutzkever wrote these essays. Markish was arrested in 1949 and executed by the Soviet regime on August 12, 1952.

The excerpt here is from a longer essay that appears in the newly released Abraham Sutzkever, From the Vilna Ghetto to Nuremberg: Memoir and Testimony (2021), translated and edited by Justin Cammy, reprinted with the permission of McGill-Queen’s University Press. The project was supported in part by a Yiddish Book Center translation fellowship and publishing grant.

I had never set eyes on Markish prior to my arrival in Moscow in 1944. I was still a teenager, studying in a Hebrew-Polish gymnasium, when Markish caused a stir in Vilna and Warsaw. My teachers hid both Markish and Yiddish poetry from me.

But his halo shone over Yiddish poetry in Poland until the Second World War.

My older colleagues, those who had seen and heard him, looked up to him as a legend. They could cite by memory several lines of Markish’s poetry, those that excited them with their beauty and wildness, like a dream chiselled in diamond.

I was jealous of those who had the privilege of being close to such a poet, to have had the chance to see and hear him declaim his verse.

If God had dreamed up a model for the creative process, something we refer to as a poet, it was probably blessed with a face, a heart, and a talent like Peretz Markish – or at least that was what I thought back then.

And when a friend lent me Markish’s volume Stam [Just So, 1921-22] I also lovingly conceived of him as a legend. But he was not necessarily my poet.

… In 1933, when I visited Warsaw for the first time, Markish’s echo still resounded within the walls of Tlomackie 13. There were many stories and anecdotes about the poet, and I don’t remember who related the following to me:

After one of Markish’s lectures at the Yiddish Literary Union, the room was bursting with such excitement that he received a half-hour applause. The only one who remained in his seat was Vaysenberg. When he was asked what he thought about Markish’s imagery, he responded: “Think of a village on a summer night. Suddenly, a spark drifts onto a tall haystack. The inferno is so incredible that it appears as though even the stars in heaven have been consumed by the flames. But a few minutes later the fire dims. That was Markish’s talk.”

*

... It was only in the Vilna ghetto that I happened across Markish’s books, and experienced both our people’s fate and my own in the dark reflection of his poetry.

I could hear the voices of those lying dead in the mass graves of Ponar crying out to me from his poem “The Mound.” Its images tore at me with their prophetic vision, revealing the mystery of our mass extermination. It was similar to the way bodies surface in a cemetery after an earthquake, and in them you recognize your closest friends, your parents, and the source of creation itself ...

… In the ghetto, the diabolical nightmare of “The Mound” was poetically logical. Its logic lived precisely where I was dying. My poisoned heart beat to the labyrinthine rhythm of Markish’s poem …

*

... July 1943. Shike Gertman, a young partisan, arrived in the Vilna ghetto from the Narotsh Forest. Fyodor Markov, the commander of the Voroshilov Brigade, dispatched him to connect with the Jewish partisans behind the ghetto gates.

I handed Shike my poem “Kol Nidre.” I asked him to forward it to Peretz Markish in Moscow, if that was possible. It was unlikely that I would live long enough to experience freedom again, but perhaps my poem could survive, a poem that bled out of me in the ghetto.

In September I once again encountered that blond-haired heroic fighter in the Narotsh Forest. He greeted me joyously: “‘Kol Nidre’ is in the hands of Peretz Markish in Moscow …”

Shike fell in battle a short time later.

March 1944. After an unbelievable odyssey by plane, I arrive with my wife in Moscow.

Justas Paleckis, the president-in-exile of Lithuania and a friend of the Jews who spoke fluent Yiddish, welcomed us to the headquarters of the Lithuanian partisans on Frunze Street 15:

“Whom do you want to see?” Paleckis inquired of us.

My wife was the first to call out: “I want to meet Dovid Bergelson … ”

“For starters, I would like to take a bath,” trying to buy time lest I give the wrong answer, “and then I want to meet Markish.”

Markish called on me at Hotel Moscow that very evening. I was standing face-to-face with the legend. His steel eyes, glowing with an inner fire, dissolved into tears. Though his eyebrows were already grey, his face appeared to be sculpted from marble.

Yes, my poem “Kol Nidre” had made its way to him from the partisan forests. It was read at a special gathering at the Writers’ House. The name of the poem’s author had been withheld, because I was still in the ghetto, and there was a fear that the Germans would track me down if they found out about me. Ilya Ehrenburg devoted an entire lecture to the poem and compared it to Greek tragedy … It would appear shortly in the collection Tsum zig that Markish himself edited.

When I accompanied Markish home a young woman stopped and gazed at him admiringly. I overhead her whisper to her girlfriend in Russian:

– He is like Byron!

*

Markish chaired my formal welcome in the Writers’ House that same week. In his greetings he remarked: “People used to point at Dante and say: that man was in Hell! But Dante’s Hell was a paradise in comparison to the hell experienced by this poet who managed to save himself … ”

His off-the-cuff remarks contained the same rhythmic emotion of his lyrics. While speaking, he grimaced in sorrow. It was as though the distant pyres of Lithuania singed him to the core …

*

… In July 1944, upon my return to Vilna, I wrote to Markish with my initial impressions of the liberated and murdered city. He wrote back to me from Moscow: “No words can provide a sufficient response. I want to smash my head against a stone. We are bound, probably until the end of days, to read this kind of ‘literature’ about our great calamity. It is our fate, and we will not escape it. I had wanted to come to Vilna, and then it occurred to me that to visit its sacred ashes would amount to a kind of desecration.”

In the end, he ended up coming to Vilna to inhale its sacred ashes. The Jewish partisans, the few thousand Jews who managed to survive, took him in as a brother. As a result of this trip, sorrow and heroism enriched his epic poem about the war, “Milkhome” [War, 1948]. He wove an array of interesting ghetto heroes into it. He even referred to them by their real names, including Hirshke Glik and Naomi (a young woman from Vilna, a partisan) …

*

... The crisis for Yiddish writers in Moscow (and Russian ones as well) came about after Aleksandrov’s pitiful article in Pravda, “Comrade Ehrenburg Gets It Wrong” [14 April 1945]. Aleksandrov took Ehrenburg to task for his alleged blind hatred of the German people. Why hadn’t he differentiated between Nazis and anti-fascists, between criminals and proponents of peace and socialism?

As a result, an entire section was removed from Markish’s poem “War,” those in which he hurls curses at the German people. In their place he inserted new fragments in which he praised Russia and her “brotherhood” with other nations.

At the time one needed to guard against even a single errant word. Blame would not fall on the censor. Ultimately, the axe would come down on the writer. The Party line was both the law and capricious. It was like walking a tightrope …

… Even in the more lenient years of 1942--1945, when the chains of Soviet dictatorship were loosened, Yiddish writers had to keep a close eye on the compass, and wherever the needle of Russian literature pointed, that’s the direction Yiddish was expected to follow …

… And just as those remaining in the ghetto did not believe that they would escape further murderous roundups, so too did the Yiddish writers in Moscow not believe that they would fare better than Kharik, Kulbak, Tsinberg, Litvakov, and tens of others whose bones lay frozen in the Siberian taiga …

*

… The tragedy of Soviet-Yiddish writers is not only that their tongues were sliced out and that their very lives hung on a single word, but especially that they had to distance and disassociate themselves from their most refined works, written in the “good years” during and after the Revolution …

*

… At the end of 1944, I proposed an article for [the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee’s paper] Eynikayt [Unity] to Bergelson, one of its editors. I had submitted the same article, “The Liberation of Underground Museums,” at precisely the same time to Mirskaya, the secretary of Literatura i iskusstvo [Literature and Art]. She was a close friend of Boris Pasternak. A Vilna Jew by the name of Shambadal translated it into Russian. He was Sholem Aleichem’s Russian translator, too.

The article appeared in the Russian journal that same week. It was word-for-word what I had submitted.

I put the journal in my pocket and made my way to Bergelson on Kropotkin Street.

“You know, I had to abbreviate your article, cross out certain names. We don’t know whether they are our friends or our enemies. Your approach is not reliable.”

“I’m somewhat baffled by your comments, Comrade Bergelson. Here is my article, printed today in Russian. Take a look. There wasn’t a single word eliminated.”

I showed him a copy of the journal.

His face turned yellow, like desert sand. There was a thin foam on his lips. It was an expression I had previously not witnessed.

“If so,” he started to gasp heavily, “I must immediately dash to the printer to restore your article to its previous form. The Yiddish must not be different than the Russian … ”

And this great Yiddish prose artist dashed to the subway. The wind blew his fur hat off his head as if the wind itself wanted to catch a glimpse of Bergelson beneath his mask.

*

I was destined to be a witness when there was an attempt to liquidate Markish, and that was still in the so-called good years. I managed to intervene on his behalf, and I consider it my obligation to relate the following:

At the beginning of summer 1945, Lozovskii, the head of the Soviet Information Bureau, called to request that I pay him a visit.

Lozovksii greeted me warmly at his office. He remained seated. He was dressed in a grey uniform with golden epaulettes, and above him on the wall there hung an oil painting of the “leader of the great land,” painted by Gerasimov. The leader was smiling at a child he was holding in his arm.

After some polite and friendly discussion, he informed me of the good news: the Lithuanian government, with his approval, had decided to honour me with the Stalin Prize.

I felt as though a net had been cast over me. A laureate of the Stalin Prize would never be given permission to leave for Poland …

“I am deeply honoured,” I feigned happiness, “but I don’t understand how I am worthy of such an honour. My ghetto poems never appeared in book form, and I do not believe the jury even reads Yiddish …”

“That’s not important,” Lozovskii interrupted my uncomfortable prattle. “Present the manuscript of your poems in Yiddish, they will be read, they will be translated …”

When I thanked him again and tried to leave, Lozovskii got up from his chair, touched the desk with his finger, and stared me in the eyes: “Yes … tell me, just between us, what is your opinion of Peretz Markish? Is it true that he wrote counter-revolutionary poems in Poland? And are you aware that here in Moscow he wrote a long poem in which he insults the Red Army?”

He removed a blue sheet of paper from his desk drawer and handed it to me.

“Please read it and tell me what you think …”

… A precise translation into Russian followed the Yiddish text. The letters were bigger in those places where Markish’s lines had allegedly insulted the Red Army.

I was curious who had denounced Markish. The text continued on the reverse side. I was not audacious enough to proceed to turn it over without Lozovskii’s permission. I let go of the sheet, and fate intervened in such a way that the paper happened to flip over on its own, so that I was able to catch a glimpse of those who had signed. They included Shakhne Epshteyn and _______. I will not provide the name of the second one, because he too was eventually a victim, shot in August 1952.

I explained to Lozovskii that from the moment I heard the name Peretz Markish he had been the symbol of Yiddish revolutionary poetry. I added that in the poetic fragment he showed me I did not catch even a trace of indictment of the Red Army. Russian Jews, who were pursued and tormented by the Germans, sought out “a place, a safe place for the night, a roof over their heads” in central Asia, and with the help of the Red Army they had found such a place.

As I concluded my testimony on behalf of Markish, a young woman appeared from another room carrying with her a document in which everything I had just said was typed out. She had been listening in on my every word, and transcribed it all in her secret office. I signed it, said my goodbyes, and left.

What was I to do? Tell Markish or not? Perhaps Lozovskii was testing me to determine whether I would tell anyone? Perhaps it was a ploy to ensnare me along with Markish? There was no certainty that my approval of Markish would be accepted!

I have to admit that the fear was even stronger. A few days before my departure for Poland, when I bid farewell to Markish at his home, I revealed the entire affair to him.

He sank into his armchair and hunched over in deep dismay and evident terror.

“I am well aware that they have been anticipating my untimely death for many years. But now, after the war, I hoped that things would be different … ”

… We left and took our final walk together through Moscow, pausing at Pushkin’s memorial.

I said to him: “I stood up for you to Lozovskii. But now I am leaving. Be strong, be careful and take care of yourself.”

Justin Cammy is professor of Jewish studies and World Literatures at Smith College, where he directs the Program in Jewish Studies. A long time member of the Yiddish Book Center's Steiner Summer Yiddish Program faculty and guest lecturer at the Yiddish Book Center, he also is lecturer on Yiddish literature at the Naomi Prawer Kadar International Summer Yiddish Program at Tel Aviv University, for which he serves as summer director. He was a translation fellow at the Yiddish Book Center in 2018 and has translated three works of Yiddish literature: Sholem Aleichem's Shomers mishpet (The Judgment of Shomer, 1888); Hinde Bergner's In di lange vinternekht (On Long Winter Nights: Memoirs of a Jewish Family in a Galician Township, 1870-1900); and a new collection of Abraham Sutzkever’s writings, From the Vilna Ghetto to Nuremberg: Memoir and Testimony, which includes the above excerpt.

*

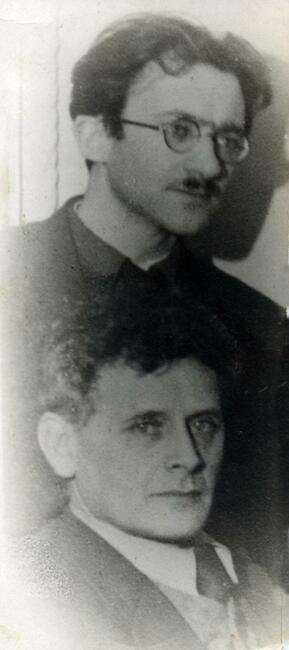

Image: Abraham Sutzkever and his wife Freydke survey a table filled with literary and artistic works that they rescued from Vilna, in their apartment in Moscow in 1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archive #64903.