The Yiddish Book Center's

Wexler Oral History Project

A growing collection of in-depth interviews with people of all ages and backgrounds, whose stories about the legacy and changing nature of Yiddish language and culture offer a rich and complex chronicle of Jewish identity.

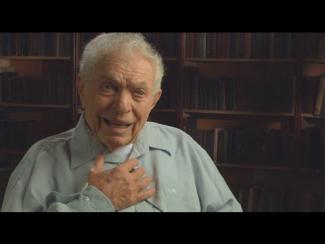

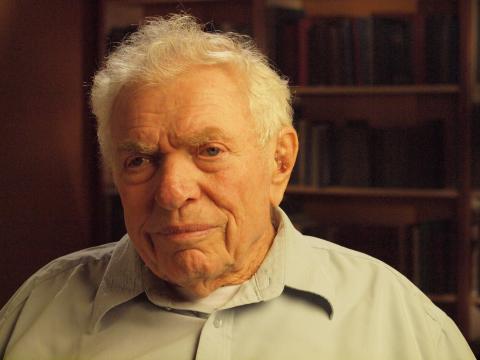

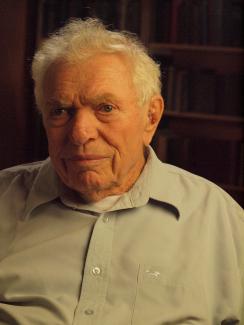

Israel Zamir's Oral History

Israel Zamir, z"l, Israeli journalist and son of Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, was interviewed by Christa Whitney on November 1, 2013 at the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. Israel describes his father's early life in Lenchen, a suburb of Warsaw, Poland. Singer was born in 1904, the son of Pinchos Menachem Zynger and Bathsheba Singer. Zynger was a dayan, or rabbinic judge, and counselled Jews at their homes on Krochmalna Street, later the subject of Singer's In My Father's Court. Israel shares his early memories from Russia and a life lived through many languages. He spoke Polish to his parents who spoke Yiddish to each other. He remembers his father coming and going and his early experiences with antisemitism. Abe Cahan, editor of The Forverts, invited Singer's brother to America and Singer followed soon after. He had promised to bring Israel to America later, but they remained separated for twenty-five years. Zamir briefly reflects on Singer's relationship with his siblings, writers Israel Joshua Singer and Esther Kreitman. The brothers had an unstable relationship, and neither of them appreciated their sister's writing or behavior. Israel explains that, as a young Socialist, he preferred his uncle's writings to his father's tales of spiritual creatures and "pornography." Israel describes his separation from Singer and his immigration to Israel. He recounts his experiences in Russia and Turkey, including seeing Joseph Stalin at Maxim Gorky's funeral. He and his mother were forced to flee Russia, and with each location came new languages. Israel had to forget Russian and speak Polish; then he learned Turkish, although his mother spoke Yiddish at home. With persistence and after learning some French, he secured visas to Israel for his mother and him. Once in Israel, Zamir continued to dream of America as his mother sent him to a Schveya School for "orphans and problem kids." At fourteen, he heard his father had died, but he realized it was actually his uncle, I. J. Singer. Israel eventually landed at Bet Alpha Kibbutz and he served in the Israeli War of Independence in 1948, later chronicled in Turn Off the Sun. Israel saw his father again for the first time after making his way to America with money owed to his father by an Israeli publisher. The "three walls" between Israel and his father, as he describes it, soon began to collapse. The first was in a cab upon arrival and realizing that as he had prepared to die in battle, Singer had had a premonition and said Kaddish for his son. The second wall was three days into his visit when he landed a job with Hashomer Hatzair [a Socialist-Zionist, secular Jewish youth movement]. When Singer discovered his son's ingenuity and $300 advance, down came another wall. The third wall led to Israel's translation work for Singer and yet another language. When Israel learned of Stalin's corruption in 1956, Singer recommended his disappointed son read The Key. He related his insights on the story to his father who decided Israel should translate Singer's works from English into Hebrew. So began Israel's unpaid translation work, annual travels to America, and learning English. Singer was a nervous person, according to Israel, who loved himself most and befriended only those connected to his writing, so it was through the translation project that they forged their new relationship. While critics disliked Singer's rewriting through translation, Israel regards both texts as brothers. He believes Singer was a great listener and a true journalist, writing modern literature with new knowledge on every page. Israel concludes with a story he had never told before, about his experiences both as a son and as an Israeli journalist at Singer's 1978 Nobel Prize ceremony. With a pressing deadline, Zamir snuck his way into the King of Sweden's bedroom and dictated his copy by phone. Security guards nearly arrested him, but he was saved by the lapel pin given to him earlier as a guest of the King. Singer's life changed forever after receiving the Nobel Prize. Israel says he became proud of his father at that point, as Singer went from a stranger to a part of his life. Israel notes that Singer's love for his son was never like that of Israel's love for his own sons. [Abstract prepared by Elizabeth Kodner Shook]

This interview was conducted in English.

Israel Zamir was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1929. Israel died in 2014.