Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt: The War Years, 1939–1945: Reading Resource Guide

A selection of the Yiddish Book Center’s Great Jewish Books Club

Issac Bashevis Singer was renowned as one of the twentieth century’s greatest Yiddish writers, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978. But for decades he was also a working journalist, contributing reportage, cultural commentary, and literary criticism to the Jewish Daily Forward, or Forverts, which was his main outlet and source of income. While most of Singer’s fiction has been translated into English, often with his own involvement, his journalism has remained almost untouched—not only untranslated but also uncollected and accessible only by going back to the newspapers in which it appeared. Even when those pieces were first published, many readers did not know that Singer was their author; his literary fiction appeared under the moniker “Isaac Bashevis,” and his journalism took the byline “Yitskhok Varshavski” (“Isaac the Varsovian”) or the more mysterious “D. Segal.” Now David Stromberg, a longtime scholar of Singer and editor of the Singer Literary Trust, has selected and translated twenty-five of those pieces in Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt: The War Years, 1939–1945 (White Goat Press, 2023), focusing on Singer’s output during the Second World War and the Holocaust.

The collection, the first in a three-volume series, casts a wide thematic net and includes some of the first pieces Singer wrote after arriving in America in 1935. The essays address issues ranging from Jewish tradition and religion—especially as they collide with the modern world—to matters of timely and political importance, such as the rise of Nazism and fascism. As the Holocaust unfolds Singer comes to grapple with its reality and consequences, not only for the millions of murdered people but also for the language and culture he holds dear. In the background of these essays is the fate of Singer’s own family, including the deaths of his mother and younger brother in Jamul, Kazakhstan, and of his older brother, Israel Joshua, of a heart attack in 1944. And while the writing is geared toward an American audience, it illustrates Singer’s attitudes toward both the old country and the new; his development as a thinker and writer; and his response and reaction to the events of those terrible years. As Stromberg points out, it was just after these pieces appeared that he began serializing The Family Moskat, an epic novel devoted to the Jewish life in Poland that had so recently been destroyed.

Four Questions

-

This book presents a different side of Singer than the one we are used to reading. How did this book confirm or defy your expectations of him? Did it complicate your views of him as a writer or thinker?

-

Many of these pieces showcase Singer’s knowledge of traditional Judaism. What do you think of his approach to religion at the time these pieces were written? Are his views still relevant today?

-

Singer often seems to be trying to educate and inform his audience. What impression did you get of the readers Singer was trying to reach, and what do you think their reaction to his writing might have been? Do you think these pieces still have value for a contemporary audience?

-

When it comes to the fate and future of Yiddish, Singer tries to strike a middle ground between pessimistic fatalism and unearned optimism. Eighty years later, do you think his approach was justified? What do you think his view would be of the state of Yiddish today?

Explore the Sections Below to Learn More about Isaac Bashevis Singer and Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt: The War Years, 1939–1945

Q&A with Editor and Translator David Stromberg

Learn about Singer’s Life and Work

Read Singer’s Writing in Yiddish and English

Listen, Watch, and Read Singer’s Talks and Interviews

Q&A with Editor and Translator David Stromberg

Yiddish Book Center: You decided to present Singer’s articles in chronological order. What will readers, and writers, notice about Singer’s progression from 1939 to 1945?

David Stromberg: Readers will notice the development of his thinking on topics like modern Jewishness, or the role of Judaism in a time when Jews are being exterminated. In general, they will see that he was constantly relating the individual to the universal, the small scale to the large. Writers will notice that Singer developed a particular style as he wrote more and more articles and became more fluent in the form that is called feuilleton, a kind of amalgam of modern-day opinion and essayistic writing.

Yiddish Book Center: All of these essays were originally published in the Forverts. What was Singer’s relationship to the newspaper?

Stromberg: Singer’s relationship with the paper was always rather complicated. In the mid-1930s, he wrote to Runia Pontsch, his ex-lover and the mother of his only child, that he never wanted to become a Forverts novelist, since the paper was associated with cheap novels that lacked literary merit. The pieces in this collection represent his return to bylined articles, though he used a new pseudonym, Yitskhok Varshavski. By the mid-1950s, people knew that Varshavski was Bashevis, but during this period it was still largely unknown. Singer also published under a third pseudonym, D. Segal, and sometimes three of his pieces appeared in the same issue—even two on the same page.

Yiddish Book Center: These are 25 essays from a pool of over 150 articles. What informed your selection?

Stromberg: The approach was to include a variety of pieces, with different topics, that also worked as a coherent whole. The pieces were also chosen because they resonated with what is currently happening in the world, speaking to the current global turmoil.

Yiddish Book Center: You begin with a piece on the Jewish law forbidding wives of missing (and often dead) husbands from remarrying. What did Singer want to say about marriage and Judaism?

Stromberg: Singer was always concerned with the blurry boundaries between tradition and the everyday. He was preoccupied with the tension between traditional life and the way that these precut forms sometimes failed to address the complexities of reality.

Yiddish Book Center: One of the pieces is titled “What Is Kabbalah?” Did Singer have a kabbalistic worldview?

Stromberg: Singer was steeped in Kabbalah from a young age. His first novel, Satan in Goray, as well as one of his early stories, “The Jew from Babylon,” showed his familiarity with kabbalistic texts and practices. The article in the Forverts shows Singer realizing that even Yiddish readers can be largely unfamiliar with Jewish tradition and mysticism. This is why he writes not only about Kabbalah but also about Jewish history and the meaning of Jewish holidays. He becomes like the Forverts’s religion writer—which befits him as the son of a rabbi but is rather ironic given his distance from religious life.

Yiddish Book Center: Singer wrote in 1942 that “we are dealing with a break in human history as a whole, with a darkness after which there must be light for a long time.” In 2024, is that “long time” coming to an end?

Stromberg: It certainly feels that way. The world order that was established after World War II is now systematically being challenged by the forces that failed to secure sufficient influence through the Cold War. While I have been following Singer’s cultural criticism for over a decade, the conflicts that are now playing out on the world stage increasingly make me feel like his writing from the war years helps us gain some perspective on current events.

Yiddish Book Center: By 1944, Singer was concerned with what he called a Jewish “spiritual fire,” or the lack thereof. Did Singer have an influence on American Jewish spirituality?

Stromberg: Singer brought innumerable people back to their heritage and tradition. I know this from the many years that I have been working on his writings—people tell me this over and over. Naturally, because he was writing literary fiction, people who delve deeper into history, and into other Yiddish or Jewish writers, discover that Singer created his own version of the past. But his version was compelling enough to get them walking down the road of discovery, and this was the role that he consciously took on as a writer.

Yiddish Book Center: You conclude the book with a piece about writing, though you could have ended on the highly topical “Answer to a Tough Question on Jewish Rights in Palestine.” What was the impetus to bookend politically relevant pieces with personal, even spiritual ones?

Stromberg: For Singer, there is no separation between the political and the spiritual, and focusing on the political alone would blur this important link. This is why following the piece about Palestine with one that discusses the spiritual challenges in writing about Jewish life is actually quite natural. Politics and art, this suggests, are both driven by the life of the spirit.

Singer’s Life and Work

As the essays in Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt make clear, Singer had a complicated relationship with modernity—embracing its opportunities while also playing the role of an old-world storyteller. These days, believe it or not, he has his own website. We assume that it’s run by his literary estate, rather than from beyond the grave, but it’s still a good place to go for introductory information.

If you’re looking for a more in-depth introduction to Singer and his large and varied body of work, there’s no better place to start than this essay by Saul Noam Zaritt, written for the Yiddish Book Center in 2018.

Read an introduction to Isaac Bashevis Singer

Parsing the relationship between Singer’s output in Yiddish and English is a job that has kept many scholars busy. However, if you’re looking for an introduction to Singer’s work in English only, this essay by Damion Searls at the Los Angeles Review of Books is quite good.

Read "A Guide to Isaac Bashevis Singer"

There are many good pieces, and entire books, to read about Singer and his work, but we would be remiss not to recommend the work of David Stromberg, the editor and translator of Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt and a longtime Singer aficionado. You can find much of Stromberg’s writing on his website, but here are a few of his essays we’d like to highlight.

“How Isaac Bashevis Singer Preserved European Jewish Life Through Literature”

“Faith in Place: Isaac Bashevis Singer in Israel”

“Was Isaac Bashevis Singer Religious?”

Singer may have been a celebrated writer, but he had a less-stellar reputation as a husband and father. When he immigrated to America in 1935 he left behind his partner, Runia Pontsch, and his son, Israel Zamir, both of whom eventually made their way to Palestine. Zamir met his father only later in life, and the two had a complicated relationship. In 2013, Zamir sat down with the Center’s Wexler Oral History Project to talk about that relationship as well as his own eventful life. You can watch a short clip of that interview below.

Watch the full oral history interview with Israel Zamir

One of the first people to translate Singer into English was Saul Bellow, who translated the story “Gimpel Tam” (“Gimpel the Fool”) into English in 1953. The story goes that Singer was worried Bellow would get too much of the credit, and from then on he worked with his own specially selected translators, who were almost always young women. In 2014 filmmaker Asaf Galay made a documentary about this arrangement, titled The Muses of Isaac Bashevis Singer. Listen to Galay discuss the documentary on an episode of the Yiddish Book Center’s podcast, The Shmooze.

Singer may have been the most famous Yiddish author of the twentieth century, but he was once a young up-and-comer, struggling to establish his place among older and more seasoned writers. It was both a help and a hindrance to him that one of those writers was his older brother, Israel Joshua, who helped him immigrate to America in 1935 and got him a job working for the Forverts. At the same time, the older brother often overshadowed the younger, at least until Israel Joshua’s untimely death in 1944. Then there was Singer’s older sister Esther Kreitman, who had her own career and reputation, although she was also overshadowed—and cruelly ignored—by both of her brothers. You can read about that relationship in The Forgotten Singer, a memoir by Kreitman’s son Maurice Carr, which was a Great Jewish Book Club pick in 2023. You can also listen to a four-part lecture series about all three Singer siblings given by Professor Anita Norich in 2013.

Learn about Esther Kreitman and The Forgotten Singer

Listen to a lecture series by Anita Norich

When Singer won the Nobel Prize in 1978, the Yiddish community celebrated—one of its own had received the most prestigious literary award in the world. At the same time, the win was not without controversy. Many Yiddish readers and intellectuals felt that the award should have gone to someone else, including deceased writers who were not technically eligible. In this 2018 essay, Yiddish Book Center President Aaron Lansky recalls the controversy in the Yiddish-speaking community of Montreal, where he was then studying Yiddish literature as a graduate student.

While there may have been controversy over Singer’s win, that did not stop Montreal’s Jewish community from celebrating. This program at the city’s Jewish Public Library was held on December 13, 1978, and features Ruth Wisse and Mordecai Husid discussing Singer’s great triumph.

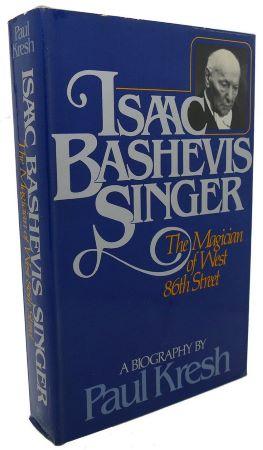

In his later years, Singer moved to Surfside, Florida, a town close to Miami Beach. But for most of his life in the United States he lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, becoming one of the neighborhood’s better-known residents. Indeed, the first biography of Singer was titled The Magician of West 86th Street. In 1990, about a year before his death, that street was named Isaac Bashevis Singer Boulevard in his honor.

When Singer died in 1991 he was mourned not only by Yiddish readers or the Jewish community but by a wide public who had come to know him through translation. Appropriately, he received quite a long obituary in the New York Times.

Read Singer’s obituary in the Times

Fittingly for an author who liked to write about demons and ghosts, Singer has had a remarkably successful posthumous career—in large part thanks to devoted readers and translators like Stromberg. In this 2019 essay for The Paris Review, Matt Levin reflects on Singer’s lasting presence and the reasons for his posthumous success.

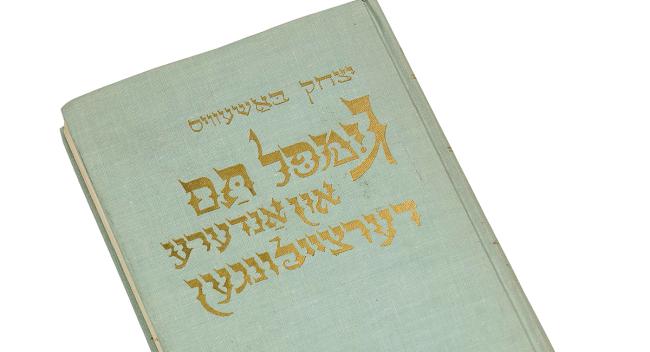

Until recently, finding Singer’s work in the original Yiddish was a frustrating experience. While many of his books were first published in Yiddish, some of them, and most of his short stories, went straight from newspapers or literary journals into English translation and could only be found by searching through microfilm. Even the books that were published were only available from certain collections or university libraries. Fortunately, in 2018, the Yiddish Book Center received permission to digitize Singer’s Yiddish books, including translations he made of authors like Erich Maria Remarque and Thomas Mann.

Read Singer’s books in Yiddish

While only a limited number of Singer’s short stories were published in Yiddish between hard covers, finding the original sources has become much easier in the digital age. Thanks to the Historical Jewish Press Archive, much of the Forverts newspaper, which was home to most of Singer’s work, is now available online. (Incidentally, the Forverts is still a going concern and can be read online here. Unfortunately, while the site does have a search function, finding those stories still takes some work. And other outlets in which Singer published, such as the literary journal Tsukunft (Future), have yet to be digitized.

Read the Forverts at the Historical Jewish Press Archive

If you’re looking for Singer’s books in English, you can likely find at least some of them in just about any library or bookstore (including our bookstore). But just as with his Yiddish work, many of Singer’s translations first appeared in periodical form. Some of those magazines not only still exist but have also digitized their archives. Below you can find the collected Singer short stories from The New Yorker and Commentary magazines, including some pretty famous pieces. You can also read a previously unknown story by Singer, edited by Stromberg and published in our own Pakn Treger magazine in 2020.

Browse the Singer archive at The New Yorker

Browse the Singer archive at Commentary Magazine

Read “Immigration” in Pakn Treger

While little of Singer’s journalistic output has been collected or translated, it hasn’t been completely ignored. Old Truths and New Clichés, a previous collection of Singer’s essays, also assembled and edited by David Stromberg, was published by Princeton University Press in 2022.

Interviews and Recordings

In his later years Singer was much sought after as a speaker and relished his role as a somewhat impish entertainer. Although that was long before the age of smartphones, he was occasionally filmed, and some of those clips have shown up on YouTube. The short documentary below features some of them, along with other clips of Singer in action.

Another gem on YouTube is a documentary, Isaac in America, which was part of PBS’s American Masters series and was produced in the mid-1980s.

The crowning achievement of Singer’s life was undoubtedly winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978. On the Nobel Foundation’s website you can access their original assessment of Singer’s life and work, as well as his Nobel lecture and banquet speech, which he gave partly in Yiddish.

Listen to an excerpt from Singer’s Nobel lecture

After his Nobel win Singer became a hot commodity, and there was no shortage of media coverage or interview requests. This long, two-part interview with the New York Times was fittingly titled “Isaac Bashevis Singer Talks . . . About Everything.”

Read an interview with Singer in the New York Times

Not everyone needed the Nobel Foundation to tell them that Singer was a great writer. A full decade before he won, The Paris Review conducted one of their famous “Art of Fiction” interviews with him, which you can read online in its entirety.

Read Singer’s Paris Review interview

Our Frances Brandt Online Yiddish Audio Library, consisting of recordings made over five decades at the Jewish Public Library in Montreal, contains several programs concerning Singer and his work but only one featuring Singer himself. This recording, made on May 14, 1982, on the occasion of the World Conference on Yiddish, included a number of speakers, but Singer got top billing.