The Yiddish Book Center's

Wexler Oral History Project

A growing collection of in-depth interviews with people of all ages and backgrounds, whose stories about the legacy and changing nature of Yiddish language and culture offer a rich and complex chronicle of Jewish identity.

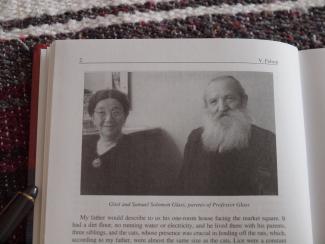

Vivian Felsen's Oral History

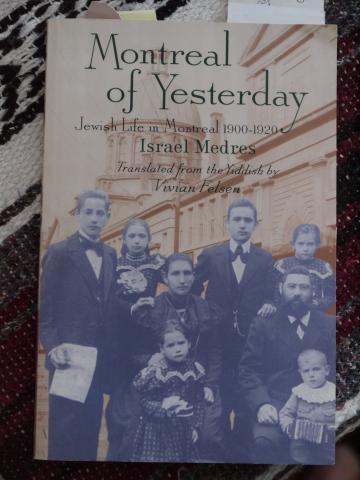

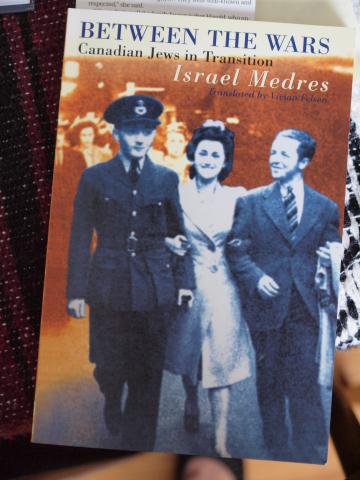

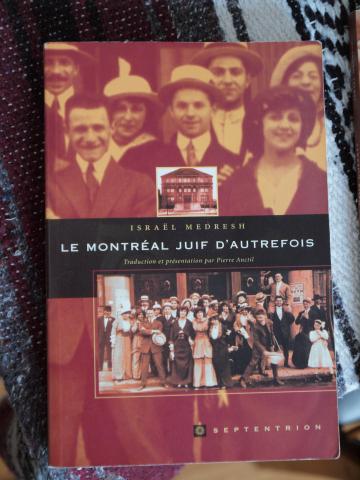

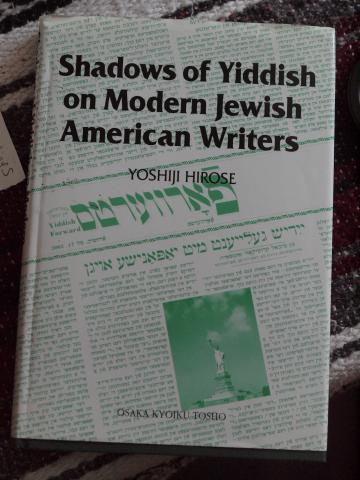

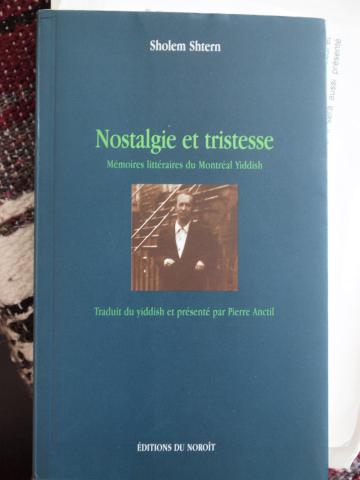

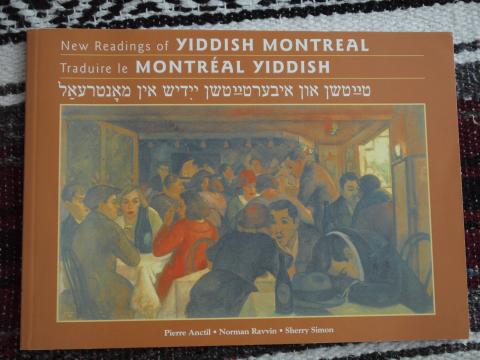

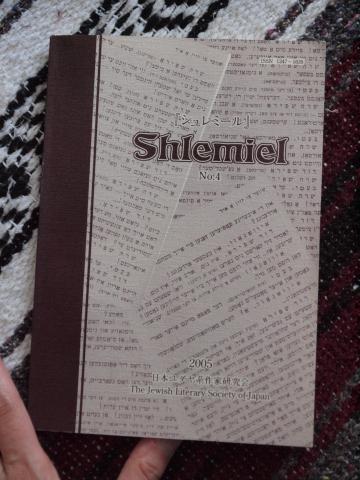

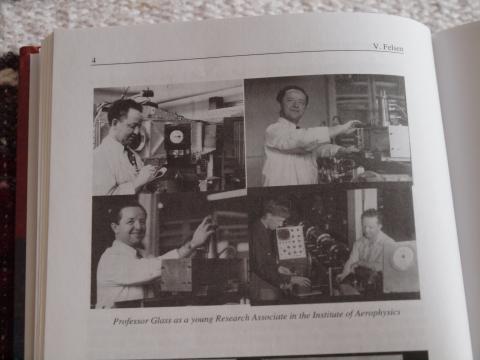

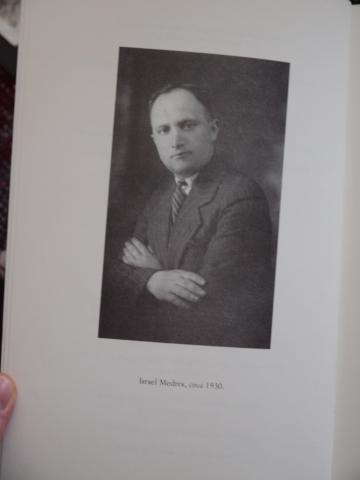

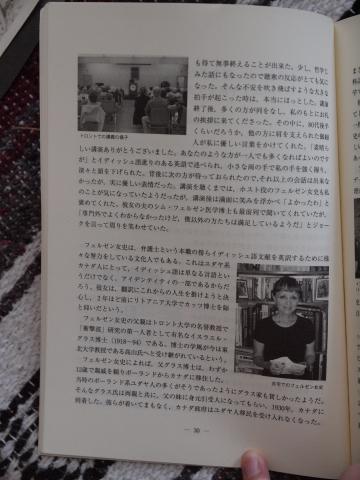

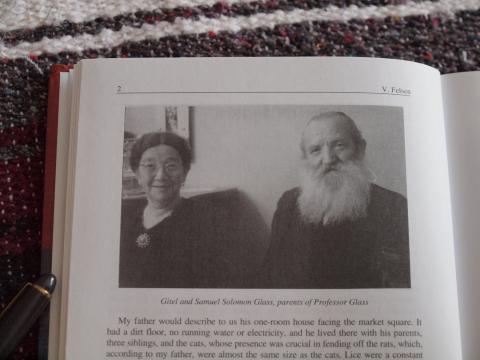

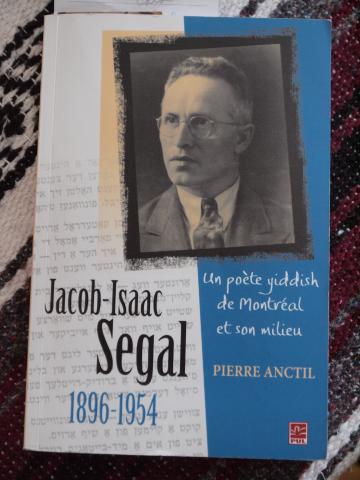

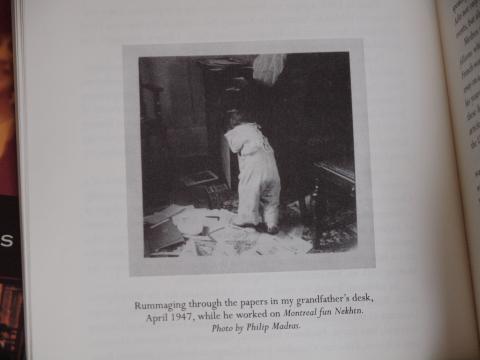

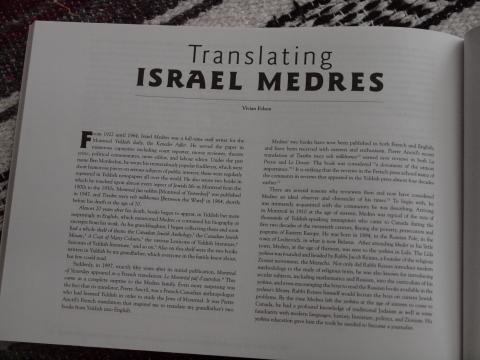

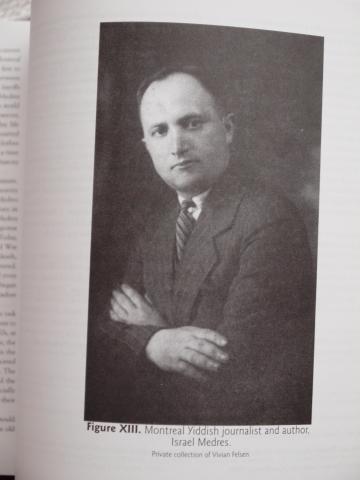

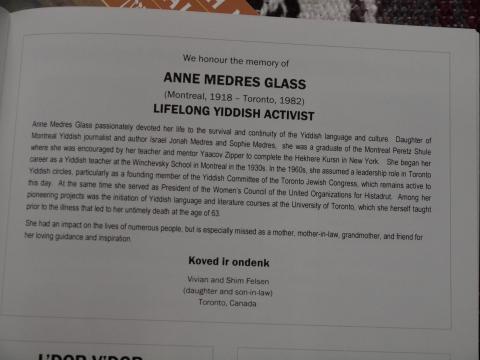

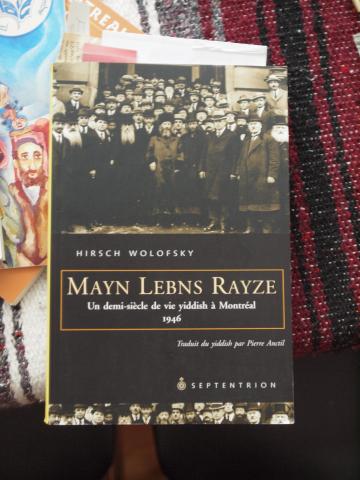

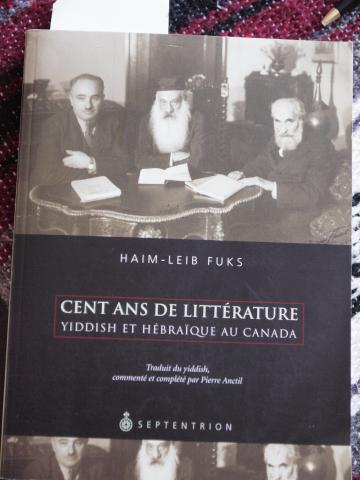

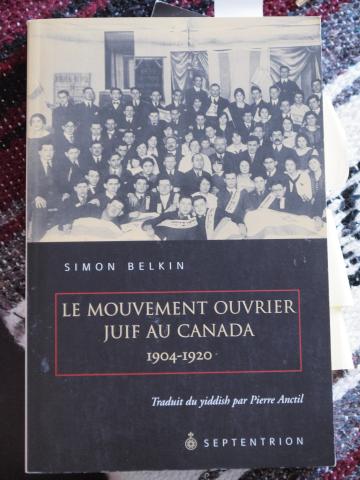

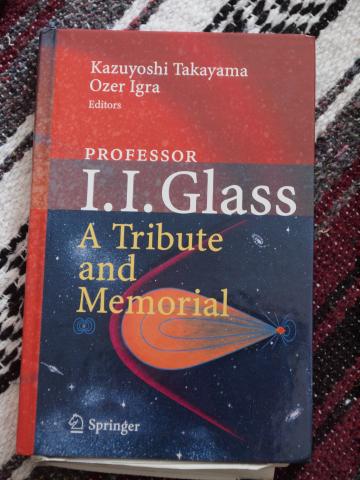

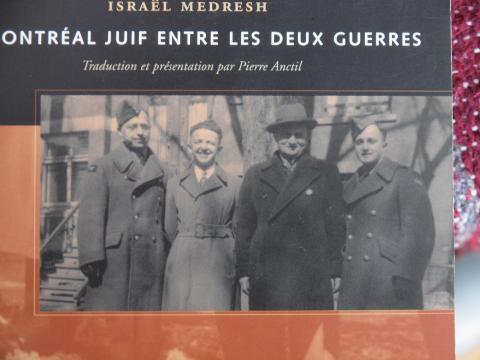

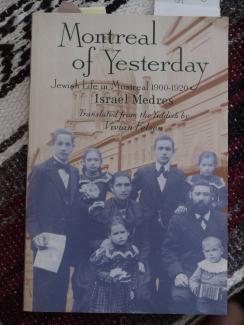

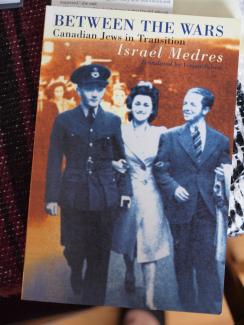

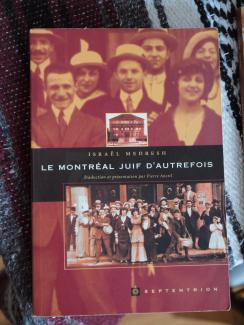

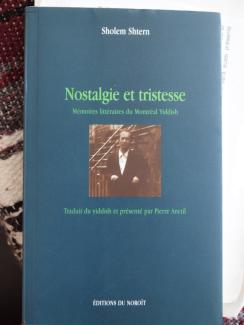

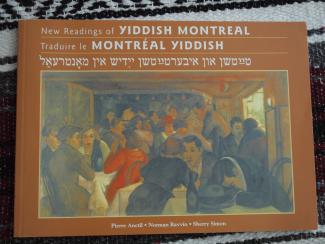

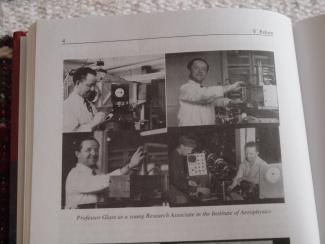

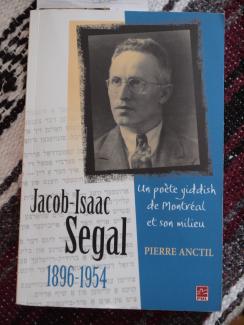

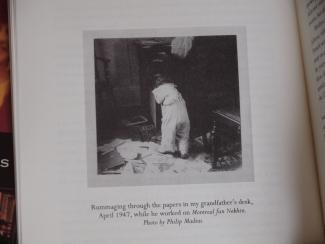

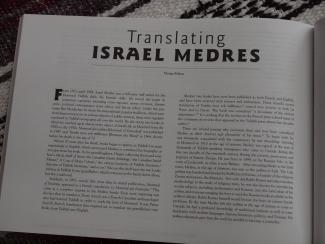

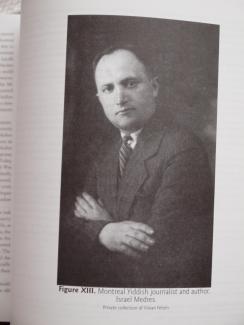

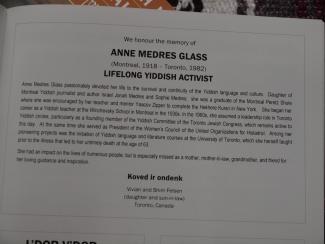

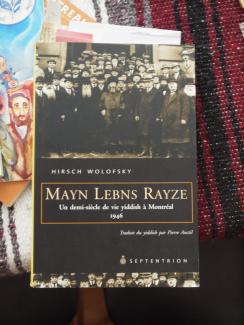

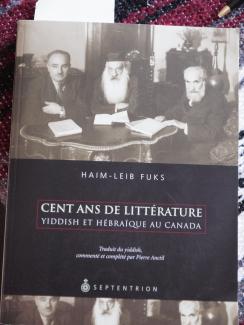

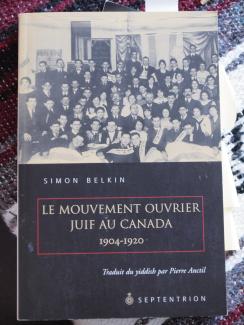

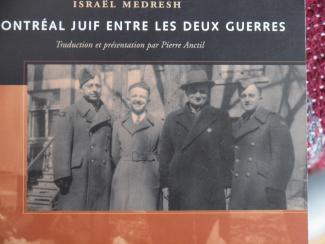

Vivian Felsen, professional translator and granddaughter of Yiddish writer Israel Medres, was interviewed by Christa Whitney on July 21, 2016 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Vivian describes her father's life in Poland and tells a story about how his grandmother carried two pails of water every day on a yoke, like an animal. Her mother, born in Montreal, was the daughter of journalist and historian Israel Medres. She became a Yiddish teacher and Communist. Medres' first book, published in 1947, was titled "Montreal fun Nekhtn" [Montreal of Yesterday], one of the first social histories of Jews in North America. He captures slices of life such as the phenomenon of Jewish boarders and errant Jewish husbands who left their families and were sometimes caught and sent back. His second book, "Tsvishn Tsvey Velt Milkhomes" [Between Two World Wars] was rediscovered and translated into French, which gave Vivian the impetus to translate it into English. Vivian remembers her grandfather, who died when she was eighteen. She recalls his interest in her schoolwork and going with him to the "Keneder Adler" building; he was the news and labor editor, and wrote humorous pieces under a pseudonym. Vivian's father became an aerospace scientist who required security clearance and so her mother needed to break ties with her left-wing friends. She struggled with her hearing and had to stop teaching for a while but eventually became the first Yiddish teacher at the University of Toronto. She died of cancer at a young age. Vivian attended the Farband Shule and then the Peretz Shule. She did not have much exposure to Judaism or the Yiddish cultural world – for her family the Jewish traditions of social justice and workers' rights were more important. Vivian explains how she became more involved in Yiddish and Yiddish translation after going to law school and realizing that she enjoyed her side job translating legal documents from French to English more than practicing law. Pursuing art as well, she met the head of Toronto's Yiddish Committee in an art class and was invited to a "Yiddish Women's Voices" conference. She began attending a Yiddish reading group and taking a class and ended up participating in the Vilna Yiddish program where she had wonderful teachers. Vivian talks about her process for translating French and Yiddish, and the tools available on the internet. Yiddish translators need to use German, Russian and Polish dictionaries as well as Yiddish ones. She believes that preserving Yiddish works through translation helps to save the rich Yiddish culture. She thinks that the language in a translation should reflect the writer's abilities, Yiddish words should not be sprinkled throughout, and glossaries should be avoided if possible. She muses about the impact of losing the generation of native Yiddish speakers on translators and the works they are translating. Vivian is now working on translating Yud Yud Segal's poetry and reflects upon his world, where literature was of paramount importance and young people were passionately involved in ideological movements aimed at making the world a better place. She is no longer translating government documents but is still making and exhibiting her art. Vivian ends the interview displaying and talking about her grandfather's books, the photographs therein, and reminiscing about some of her friends and colleagues who also translate Yiddish books. Her advice to would-be translators is to learn as many relevant languages as possible, expand your Yiddish vocabulary, and focus on the English of the final product, which becomes more important than the "source" language.

This interview was conducted in English.