Chaim Margoles-Davidzon: Writing Against Fascism

On the eve of World War II, the Bronx-based author and typesetter created a singular collection of illustrated, anti-fascist stories

When exploring the Yiddish Book Center’s vault, my eyes are often drawn to books with illustrations on the cover. While illustrations can be a quick access point for understanding a book’s contents, they can also provide insight into a work’s tone—something not easily gathered by skimming the table of contents.

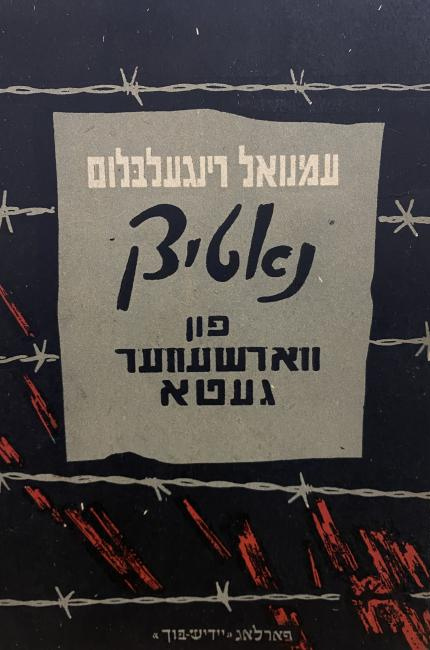

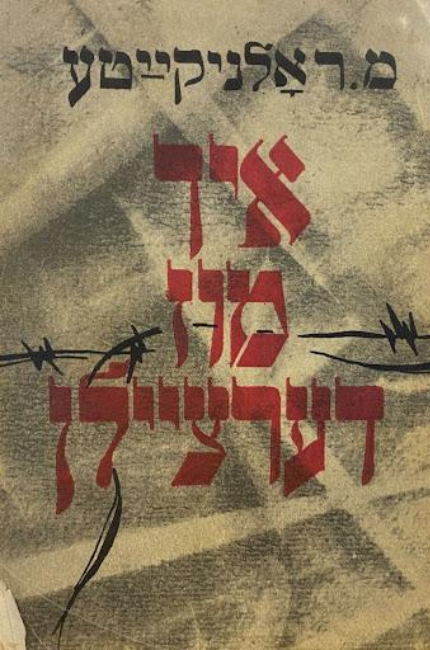

I frequently come across works on the Holocaust that feature the same motifs: barbed wire, fire, and the smokestack. Even in the early years of Holocaust memory, these images were synonymous with the Holocaust and conveyed feelings of oppression and solemnity. In particular, the exclusion of human figures from illustrated covers contributed to the conceptualization of the Holocaust as an unimaginable, irrepresentable moment in history.

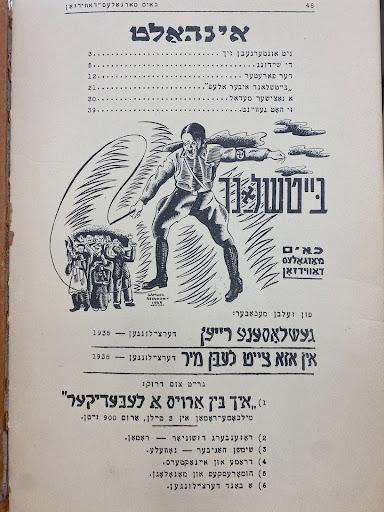

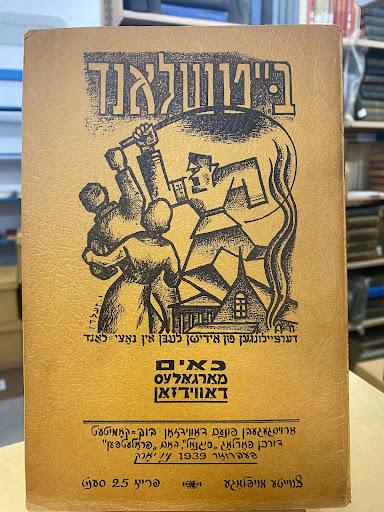

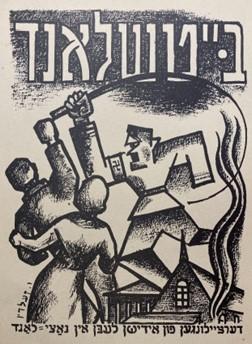

You can imagine my surprise when I stumbled upon Chaim Margoles-Davidzon’s Baytshland: dertseylungen fun idishn lebn in natsi-land (Baytshland: Stories of Jewish Life in Nazi-Land), a story collection embellished with striking, active cover art: a Nazi official brandishing a whip, his arms posed in a half-swastika.

The graphic cover art alone caught my attention, pulling me into the world of Baytshland. I was transported to the 1930s, when reports of the horrific discrimination Jewish Germans were facing at the hands of the Third Reich filled American Jewish newspapers. In response, Yiddish writers like Margoles-Davidzon transformed their horror into creative protest, hoping to mobilize the American masses to speak out against the Nazi foe.

Baytshland begins with a foreword boldly calling its readers to action:

This book is meant to remind my Jewish brothers that their redemption is on the side of progress; that fascism—the most brutal form of reactionism—brings to them, just like to all classes of people, only tears, blood, and—death . . .

Let it also serve as a comfort that not everyone in that occupied country is seized by the wild beastliness of Nazism and fascism, and that a kind of strength still resides there that will, in the end, dismantle the rule of those savage Nazi cannibals! . . .

דאָס דאָזיקע בּיכל איז אף צו דערמאָנען מיינע בּרידער אידן, אַז זייער דעלייזונג איז

אף דער זייט פון פּראָגרעס; פאַשיזם — די בּרוטאַלסטע פאָרם פון רעאַקציע — ברענגט פאַר זיי, פּונקט װי פאַר אַלע אַנדערע שיכטן פון פאָלק, בּלויז טרערן, בּלוט און — טויט . . .

זאָל דאָס אויך דינען װי א טרייסט, אַז אין יענעם פאַרגװאַלטיקטן לאַנד זענען װייט

ניט אַלע בּאַװאוינער פאַרכאפּט מיט דער װילדער בּעסטיאַלישקייט פון נאַציזם און פאַשיזם

און אַז עס לעבּט נאָך דאָרט דער קויעך, װאָס װעט סאָף־קאָל־סאָף פאַרניכטן די הערשאַפט

פון די װילדע נאַצישע מענטשן־פרעסער! . . .

Margoles-Davidzon asks his readers to stand on the right side of history—with “progress,” not “reactionism”—and to remain confident that with outspoken sympathy from their non-Jewish neighbors, the Nazi foe would be defeated. Following the foreword, Baytshland contains five short stories depicting scenes of Jewish suffering, from a violent episode of deportation to a tragic tale of a “mixed-race” family.

The publication of Baytshland was not the first time Margoles-Davidzon called upon his readers to take action. Throughout his career, Margoles-Davidzon acknowledged the power of his relationships: with his readers, with his Book Committee, and with the wider leftist writing community. Who was Chaim Margoles-Davidzon, and how did he produce the eye-catching anti-Nazi book that was Baytshland?

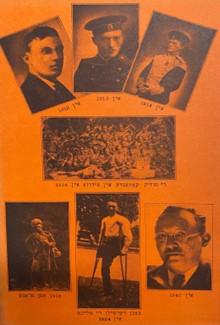

Chaim Margoles-Davidzon (also known by his American name, Herman Davidzon, or Chaim Mardavi, a contraction of his hyphenated last name) was born in Warsaw on January 14, 1891. The son of a soap maker, Margoles-Davidzon received a broad education in religious and secular subjects before learning sign painting as his trade. As a young man, he acted in the Rappel and Kompanyeyets Yiddish theater troupes. In 1912, he left Warsaw to serve in the army and fought on the Turkish front during World War I. After the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Margoles-Davidzon lived in Tiflis (Tbilisi), the capital of the Republic of Georgia, where he briefly worked in the Yiddish theater. Around this time, Margoles-Davidzon lost a leg due to a lifelong illness and began navigating the world with a prosthetic limb.

In 1921, Margoles-Davidzon sailed from Constantinople to the United States, with his wife Jennie and infant son Louis, to join his parents in New York. The family made their home in the Bronx, where Margoles-Davidzon worked as a typesetter for many years. As a writer, he quickly integrated himself into the circle of pro-Soviet Yiddish writers that would, in 1929, become Proletpen (Proletarian Pen), the largest Yiddish communist writers’ organization.

Margoles-Davidzon’s arrival on the writing scene in 1921 came at a significant political moment in American Yiddish press and publishing. Only a year after his arrival in the United States, Yiddish writers in New York coalesced around two camps: “Di linke” (those on the left) and “Di rekhte” (those on the right). Both camps were socialist, but diverged in their support for the Soviet Union. Pro-Soviet writers gathered around the newly founded daily Frayhayt (Freedom), while anti-Soviet writers worked with the Forverts (Forward).

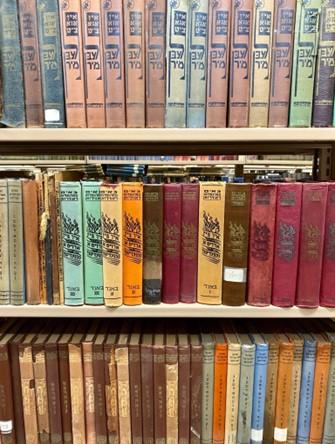

Margoles-Davidzon, a member of the American Communist Party, stood firmly with Di linke, publishing most of his stories and memoirs in the Frayhayt, as well as other leftist publications such as Hamer (Hammer), the monthly Signal (Signal), the Kovno-based Funken (Sparks), the anthology/almanac Yunyon-skver (Union Square), and Der for-arbeter (The Furrier). He published over a dozen books, many of them under Proletpen’s imprint, Signal.

Di linke prided themselves on including political perspectives in their publications. From Hitler’s accession of power in 1933 onward, the Frayhayt championed the anti-Nazi cause. In 1938, Proletpen published an anthology titled Khurbn daytshland (The Destruction of Germany). It was in this atmosphere that Margoles-Davidzon published Baytshland with Signal and shed further light on the early horrors of the Holocaust as it was occurring.

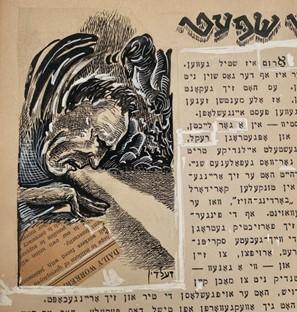

Hoping to attract a wide audience, Baytshland took an unmistakably sensationalist approach to an otherwise dark and disturbing topic: the lives of Jews under the Third Reich. The title presented readers with a compelling play on words, combining Daytshland (Germany) with baytsh (whip). This violent mental image was complemented by the stark cover art.

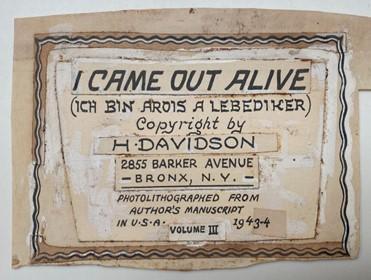

The cover was illustrated by poet and playwright Yashe Zeldin. Born in Vilna in 1902, Zeldin made his name as a writer but is also credited with illustrating his own work, Yam-lider: lider un poemes, and others’, like B. Mozer’s Beni: kinder-roman. At the time of Baytshland’s publication in 1939, Zeldin lived in Moscow. He voluntarily reported for the army in 1941 and, according to the Yiddish Writers Lexicon, died in battle within a year. However, Zeldin’s illustrations are featured in Margoles-Davidzon’s works until 1947, including Geshlosene reyen (Signal, 1935), In aza tsayt lebn mir (Signal, 1938) and Ikh bin aroys a lebediker (Signal, 1941–1944).

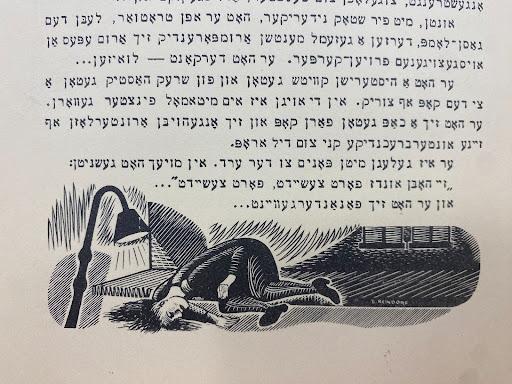

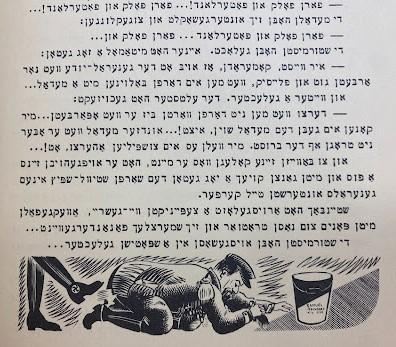

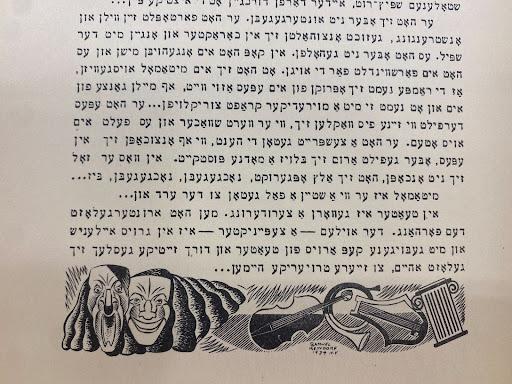

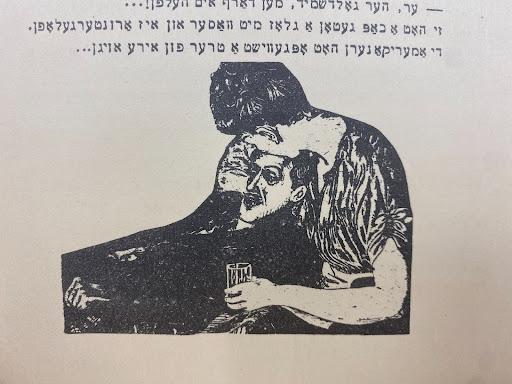

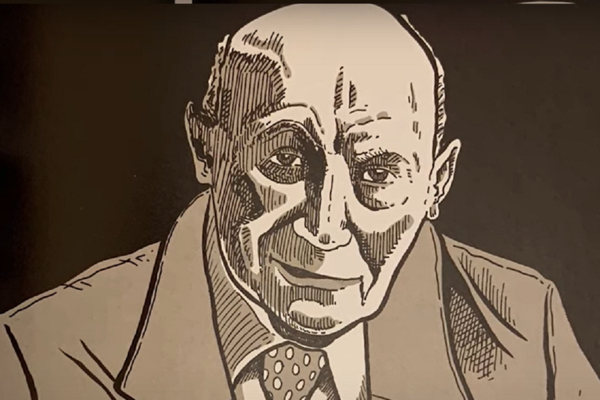

Throughout Baytshland, Margoles-Davidzon also includes original illustrations from visual artist Samuel Reindorf. Likely a relative of Margoles-Davidzon's, Reindorf was born in Warsaw, in 1914. He spent 25 years in New York, where he ran an art advertising business, before moving to San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico, in the 1950s.

Illustrations by Samuel Reindorf

Although little information exists about Margoles-Davidzon outside of his published works, one thing is clear: he believed deeply in the political power of aesthetics.

Not only did he frequently include evocative illustrations by Zeldin and Reindorf in his novels, plays, and short stories, he also hand typed and photolithographed all of his own works. Around the time of Baytshland’s publication, photolithography was becoming increasingly accessible thanks to new offset printing press technology. Using a special typewriter made specifically for his aesthetic needs, Margoles-Davidzon carefully formatted each page in every book, even cutting and pasting words by hand when they didn’t fit quite right.

Of course, for communist writers, the printed word itself was also charged with political potential. Following the standard orthography dictated by Soviet language authorities in the 1920s, many communist writers wrote in phonetic Yiddish and, after 1932, dropped the “final” versions of Yiddish letters. Although he did not follow Soviet orthography exactly, Margoles-Davidzon wrote in phonetic Yiddish.

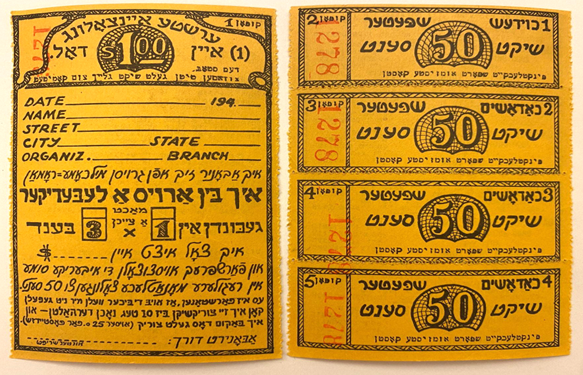

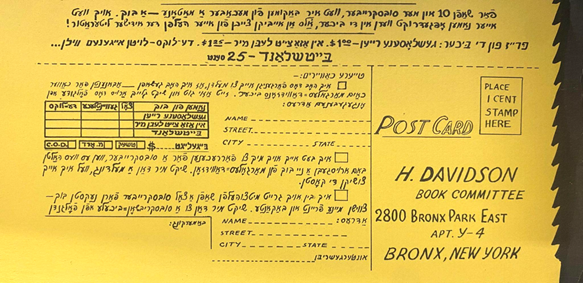

His careful eye for detail stretched even further than his published works. In communications with the Davidzon Book Committee, a group of readers who crowd funded his work, Margoles-Davidzon continued his curated authorial brand. He wrote members of the committee letters, hand signed copies of books for them, and sent out decorative marketing materials like bookmarks and coupons.

In our collection alone, we have dozens of hand-signed copies of Margoles-Davidzon’s works.

Flipping through their pages, pieces of ephemera continue to reveal themselves—much to my delight!

In this time of crisis, Margoles-Davidzon turned to his community to share a message of solidarity and strength. He collaborated with visual artists to publish bold stories that would spark compassion for the vulnerable Jews of Europe. He was empowered by a community of leftist Yiddish writers who used their presses to decry fascism from afar. He relied on his book committee’s support to publish the anti-fascist stories of Baytshland and represented their politics in doing so.

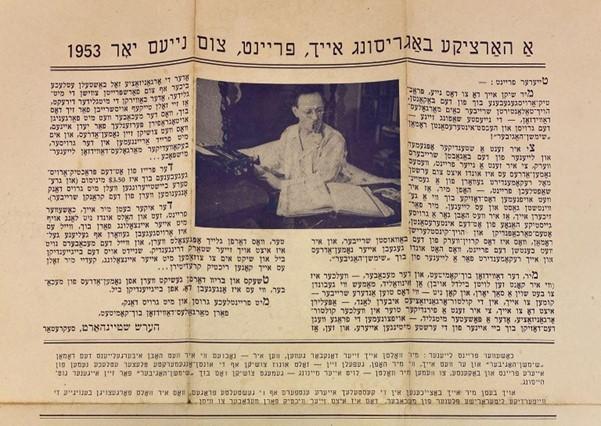

Margoles-Davidzon passed away in 1960, shortly after losing his second leg and becoming completely bed-ridden. In his obituary in the Morgn frayhayt, Sh. Almazoff remembered him fondly:

"If there ever was a person whose life was a long chain of fearful suffering, it was this recently deceased man. If there ever was a person who battled with his life with all of his strength, not paying attention to all his suffering and who was master of his domain, it was Margoles-Davidzon. And if ever a writer had wherever and whenever proceeded with his work under conditions that could kill every opportunity for creative and inventive devotion, Chaim Margoles-Davidzon was that writer. He never looked at life from his unreal, gloomy suffering. Despite all the effort, and despite the hardest conditions, he was unrelentingly productive and created works of the most important kinds."

While he could have remained silent, Margoles-Davidzon chose to write about the devastating stories coming out of Germany in 1939. Considering its material, literary, and historical legacies, Baytshland is a testament to the power of creativity, community, and protest in the face of apathy and oppression.

— Written by Maya (Zuni) González, 2023–2024 Harriett and Seymour Shapiro Fellow

Thank you to Ruby Landau-Pincus, Reference & Outreach Archivist at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York, for their help in accessing Chaim Margoles-Davidzon’s papers.

The Bronx Bohemians blog is made possible with the support of the Lynn and Greendale families in memory of their aunt and mother, Zeva Greendale, and her special passion for yidishkayt.