Crotona Park: A Yiddish Haven in the Bronx

The Bronx’s Crotona Park, as depicted in Yiddish literature, is a place to relax, reflect, organize, and fall in love.

Yiddish New York City evokes a certain set of landscapes— streets teeming with pushcarts, jam-packed tenement houses, and airless sweatshops. But what happened as hundreds of thousands of people swapped cramped and bustling Essex Street for the roomier, leafier avenues of the Bronx? What kinds of Yiddish-speaking communities were formed in the borough, both by European-born generations as well as their children?

I first encountered a Yiddishist youth culture that was fun, flirty, and intrinsically tied to the Bronx while I was a Steiner Summer Yiddish Program student in the summer of 2021. The musician and sound archivist Lorin Sklamberg led a song workshop for us over Zoom, and he introduced my class to a song I still hum under my breath, a song that offers a peek into a time when first-generation young people were figuring out their identity as American Jews, speaking a “Yinglish” that dances between two worlds.

The song was recorded by the folklorist Ruth Rubin in 1967 and was sung by Feygl Yudin, one of Rubin’s primary “informants.” Take a listen below and follow along with the lyrics to hear the story of a Crotona Park love affair gone bad.

I will never fall in love again,

I will not go to Crotona Park anymore,

Crotona Park should become a wasteland,

As that’s where my misfortune was.

I used to go to him on the subway,

Up to 180th Street,

I supported him

Until he finished college,

Now he says he doesn’t know me anymore.

Now he has another beloved,

He goes to the movies with her.

Oh, desolation should come to them both,*

And in his heart should sit a tumor.

I will never fall in love again . . .

*Alternately:

They should be made to walk on crutches [or]

A curse on his dead father.

כ'װעל שױן מער אין קרעטאָנע פּאַרק נישט גײן,

אױ, אַ װיסטעניש זאָל קומען אױף קרעטאָנע,

אױ, דאָרטן איז מײַן אומגליק געשען. מיט דער סאָבװײ פֿלעג איך צו אים פֿאָרן

ביז הונדערט־און־אַכציקטע סטריט,

כ'האָב אים סאָפּאָרטעד

ביז ער האָט געפֿינישט קאַלעדזש,

איצטער זאָגט ער אַז ער קען מיר שױן נישט. איצטער האָט ער אַן אַנדער געליבטע,

ער גײט אין די מוּװיז מיט איר.

אױ, אַ װיסטעניש זאָל קומען אױף זײ בײדן

*און אין האַרצן זאָל זיך אים זעצן אַ געשװיר. כ'װעל שױן מער קײן ליבע נישט שפּילן... אָדער׃*

אַז גײען זאָלן זײ אױף קוליעס [אָדער]

אַ רוח אין זײַן גפּגרטן טאַטן.

Besides the charming interplay of languages (such as “gefinisht kaledzh”), the song is so appealing because it allows the listener to feel like an eavesdropper in the speaker’s life, even as she bitterly curses her ex and the whole social scene they were a part of. (Feygl Yudin said her group of friends modified Maud’s original line about the dead father because they felt it was too extreme.) But it’s not just the narrative of the song that captivates— it’s the sense of a whole landscape, suggested by hints of geography such as the park and the 180th Street subway station. When listening to this song, I can almost see groups of friends lounging in the park, flitting in and out of relationships as easily as butterflies gliding over grass, a time of transition for Yiddish culture but also a moment of exciting youthful creativity.

Not too long after, I encountered a poem by a favorite modernist poet and Bronx resident, Anna Margolin. “Girls in Crotona Park” paints a beguiling portrait of cool autumn evenings and girls dressed in “lavender, faded rose, and apple-green,” with “dew flowing through their veins.” It made me even more curious about this mysterious place, at once a city park with a utilitarian function but also a place of social connection and coming of age. By diving into the Yiddish Book Center’s OCR search function, I was able to uncover texts depicting Crotona Park as a location for amusement and fresh air, as an important gathering place for literary and political groups, and as a semi-public, semi-private space for personal reflection and community formation during the first half of the twentieth century.

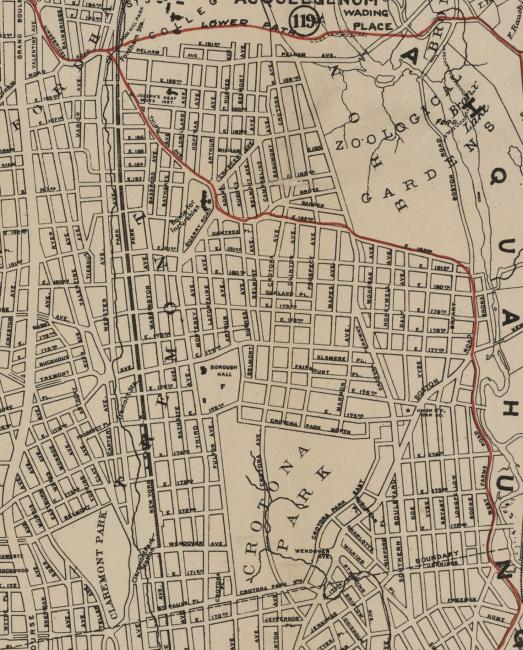

Crotona Park has served Bronx communities since 1888, when the area was still largely German. But around the turn of the twentieth century, the neighborhoods south of Tremont Avenue were urbanized as Jewish immigrants and their families moved away from the overcrowded Lower East Side of Manhattan. The humorist Tashrak satirizes this switch in a 1904 newspaper sketch: “The [German] saloon-keepers sigh . . . The new neighbors arriving in the Bronx drink mainly seltzer and soda-water.” Once the earliest newcomers braved the long subway ride and sometimes hostile neighbors, the lure of spacious apartments and quieter streets brought many, many more. The change-over was so dramatic that by 1930 Jews made up 49 percent of the whole borough.

For writers and other creatives, the move to the Bronx signaled a different kind of Yiddishist social life—trading the rambunctious downtown cafes, where one could get in fiery debates about prose style over a bowl of borscht, for a more dispersed circuit of salon visits and cultural evenings, exemplified by the Kling family. In his 1933 collection of reminiscences, Zishe Weinper recalls going on a nighttime stroll through Crotona Park with Joseph Opatoshu after just such an evening:

It wasn’t just families who needed green space but also writers! It’s moving to imagine Opatoshu prompted into spontaneous song by the friends’ sudden arrival into a forest in the midst of six-story apartment blocks and elevated trains. This bit of wilderness was a literal breath of fresh air for a generation of Yiddish writers who wanted to break away from the sweatshop tradition of didactic poetry for the masses and instead create more personal, expressionist literature. (Though most writers in this social scene still worked day jobs to survive.)

Another writer with a notable connection to Crotona Park was Hinde Zaretsky, previously profiled at the Bronx Bohemians blog. Zaretsky lived a couple of blocks away from the Klings, at 811 Crotona Park North, directly facing the park. Few writers captured the precise terrain of the green space as specifically as Zaretsky. In one poem she mentions the geologic legacy of boulders that dot Upper Manhattan and the Bronx, describing their imposing forms as “prehistoric animals at rest.” Other poems depict children at play:

Mothers, loyal shepherds

Watch over their lambs.

Boys hop around like rabbits

Atop the backs of boulders in Crotona Park.

געהיט זײערע שעפֿעלעך. אױף רוקנס פֿון פֿעלדזן אין קראָטאָנאַ פּאַרק

געשפּרונגען װי די האָזן האָבן יינגלעך.

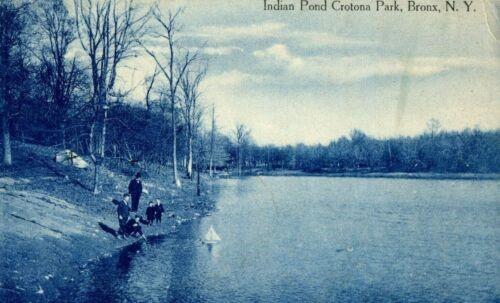

Hinde Zaretsky was a kindergarten teacher who frequently wrote literature for young people, and like many authors she understood that play is never only play—children’s games are a way of practicing for adulthood. In the title poem of her book Krotone park brigade, the eponymous brigade is made up of kids from neighboring streets (Webster, Bryant, Pelham Bay) convening by foot, bicycle, and roller skate. One “simple Wednesday,” the brigade meets up by the lake to sail model ships. But this was 1948, so the little ships transcended the balsa wood or twigs they were made of— in the children’s imagination, they were safeguarding displaced persons across the sea on their way to the newly founded state of Israel. Thus, Crotona Park was not a place bound only by the city’s grid. The park could expand limitlessly based on the games and whims of the green space’s most loyal patrons, and real-world troubles and traumas could be safely played out among the ponds and grassy hills.

For many women like Hinde Zaretsky, caught between day jobs, creative callings, and familial responsibilities, the park was beloved simply because it did not ask anything of them. More than a melancholy landscape missing the sounds of kids at play, as it appears in some of Zaretsky’s poems, the park by night could also be a place of serenity and self-reflection. In the following passage from Sh. Dayksel’s story “The Swan Song,” Rivke spends some time lost in thought on a park bench after she finds out she’ll be joining a folk choir and singing for an audience for the first time. As the narrative follows her swirling thoughts, readers can understand just how important Crotona Park was for the mental well-being of many neighborhood residents:

Dayksel captures the particular feeling of being alone even when surrounded by thousands of people, but solitude in the park feels different than solitude on the subway or streets. Once Rivke reaches the forgiving darkness of Crotona Park, she doesn’t have to contend anymore with the “thousands of searching, disorienting glances.” She can be anonymous, looking at her own windows as if she were a stranger, taking stock of the twists and turns of her life. For women like Rivke, the park, despite ostensibly being a public place, offered more privacy and space for reflection than noisy homes crammed full of family members.

As seen before in Anna Margolin’s poem, Crotona Park (during the day at least) was also a kind of parade ground for young people of dating age, a place to show off the latest fashions and gossip with friends. But at the same time the park was used by people of all ages and levels of assimilation, such as “the bearded Jew” among the groups of more secular-minded young people in the following passage from Solomon Davidman's 1936 novella Children of New York:

What unites all the assorted park-goers in this scene is Davidman’s attention to sensory delight and physicality— young men on a walk, the grandmother pushing a stroller, the conversations with hands, even the religious Jew caressing his beard as if it could offer protection against all these worldly pleasures.

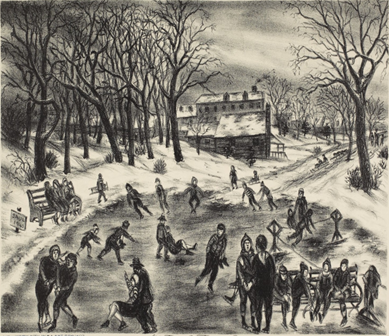

For younger people especially, Crotona Park was an important neutral ground for courtship and dating, free from the watchful eyes of parents and guardians who may not have approved of men and women of marrying age going on strolls together down “grassy, untrodden paths.” But oftentimes, young people’s romantic and political awakenings happened simultaneously in Crotona Park. As Leo and Frances read the Communist literature they brought with them to the park, they learn more about each other by discussing Wall Street exploitation and the activities of the youth organizations they’re a part of. The aforementioned “Russian Hill” was a large boulder known for the meetings, speeches, and tempestuous debates that were held there, oftentimes by Bundists versus Labor Zionists or between those who stood with or against the Soviet Union.

In another story, “On Russian Hill,” Solomon Davidman describes groups of people convening at the boulder in the evenings, exhausted from long days of work but with smiles on their faces. Although some in the crowd had been revolutionary agitators in the old country and had escaped from prisons and Siberian exile, Davidman describes the meetings in Crotona Park as unpretentious, warm, and inviting, with men taking off hats and jackets to relax and enjoy an evening in the park with their comrades. As with Feygl Yudin and her friends who had learned the “Kretone Park” song together, the main activity around Russian Hill was singing. As Davidman writes, they sang songs of “freedom and joy of the future, in many languages, from various countries, in one big choir.”

In the Yiddish literary world, the Crotona Park Gang met at a cluster of boulders by the northern end of the park, while Di yunge (literally, “the young ones”) met both downtown and in salons around the neighborhood. Members of Di yunge would go on strolls in nice weather, circulating their ideal of “art for art’s sake” among the “graphomaniacs” that filled the park at all times of day, according to one of the yunge, A. Glanz-Leyeles.

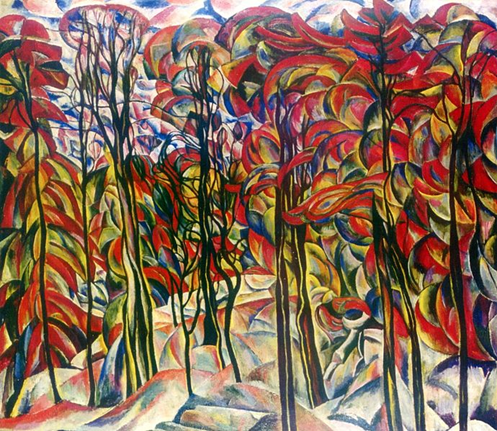

Besides literature and music, visual art was also cultivated among the garden beds of Crotona Park. The most well-known artist of this milieu is the painter Abraham Manievich, a post-impressionist who had a successful art career in Eastern Europe and Paris but had to flee Kyiv during the Russian Civil War. Manievich was friends with writers like David Ignatov and other members of Di yunge. But Abraham Manievich had lost his son in the civil war and had difficulties adjusting to American life. In his book on Jewish artists, Jacob Rashell describes Manievich going on strolls through Bronx parks, so deep in his thoughts that many people assumed he was misanthropic.

In paintings such as Autumn, Crotona Park, Manievich expresses the energy of the park through his vivid and enchanting color schemes, as well as his Cubist geometric forms. As Rashell describes, Manievich did not just copy a landscape; he transformed his vistas and imbued them with all the optimism and longing of his generation. Unlike other Bronx paintings by Manievich, Autumn is not crammed with buildings or other man-made forms. The groves of trees seem to stretch on forever in whirls of color, a place where one could get lost even within the most populated city in the world.

The park was known for its youthful and colorful culture, but intergenerational connection still occurred by chance on the meandering twists and turns of dirt paths. Such an example can be found in the work of H. Leivick, one of the most celebrated Yiddish poets, as he elegizes Morris Rosenfeld, who epitomized the previous sweatshop generation of Yiddish poets in New York:

I saw him for the last time in Crotona Park:

Standing there with a bowed head,

Under an autumn tree, and a full moon

Cast its light upon him, sheaves after sheaves . . .

“How do you do, Rosenfeld?” I asked.

He raised two wondrous eyes,

With much unexpected warmth and light:

“You know, maybe not all my poems hit the mark—

But now I’m singing my last verse . . .

Good night, good night, my colleague”—

And he strode away murmuring a stanza.

ער איז געשטאַנען מיט אַן אײנגעהױקערטן קאָפּ

אונטער אַ האַרבסטיקן בױם, און אַ פולע לבנה

האָט געװאָרפן אױף אים ליכט סנאָפּ נאָך סנאָפּ... — װאָס מאַכט איר, ראָזענפעלד?— האָב איך געזאָגט. ער האָט אױפגעהױבן צװײ װאונדערלאַכע אױגן,

מיט אַזױפיל אומגעריכטער גוטסקײט און ליכט׃

איר װײסט, מײנע געדיכטן ניט אַלע, אפשר, טױגן–

אָבער אָט זינג איך איצט מײן לעצט געדיכט… אַ גוטע נאַכט, אַ גוטע נאַכט, קאָלעגע— — —

און אַװעקגעשפּאַנט מורמלענדיק אַ סטראָף…

Reading this poem, I get the sense that Leivick was dramatizing a passing-of-the-torch moment, a feeling that the park, and by extension the whole literary community, was now a place for the young. True to Leivick’s style, the landscape in this poem is full of dreamy archetypal imagery like the moon and trees, and the only detail tying the work to a concrete reality is the mention of it taking place in Crotona Park. Crotona Park, with its Old World alleys of trees and “Russian Hill,” could therefore exist as a more neutral space between one generation and the next, a place where poets like Rosenfeld could access such poetic inspiration as moonlight unfiltered by streetlamps. Morris Rosenfeld being depicted among the natural world is particularly meaningful considering the decades he spent within sweatshops without access to the natural imagery younger poets were now turning to.

As American Yiddish literary production outpaced Europe, New York City locales such as Crotona Park began to be mythologized in much the same way as Peretz’s salon was in Warsaw or the Strashun Library in Vilna. This was most evident in the postwar era, when Jews started moving northward in the Bronx or out of the city altogether. For example, in a 1968 poem, “Bronx,” Y. Y. Schwartz, once a member of Di yunge, remembers the golden age of the literary salon culture in his poem. About Crotona Park, he writes, “Nest of dreamers / and young visionaries; each / with his own radiance and shine, / enamored, captivated by the word and poem.”

Beginning in the ’50s and reaching a low point in the ’70s, white flight, disinvestment, and budget cuts in the Parks Department contributed to the decline of living conditions in the neighborhoods around Crotona Park. African American and Puerto Rican newcomers were forced to contend with South Bronx landlords setting buildings ablaze as well as violence and a drug epidemic. In the early ’50s, the northern part of Crotona Park disappeared beneath the Cross-Bronx Expressway, displacing thousands of residents and severely worsening air quality. Although Crotona Park saw moments of low usage and neglect during these challenging years, neighbors and community activists never gave up on the green space. A turning point was reached in 1996, when the Friends of Crotona Park organization was founded in order to maintain amenities such as the swimming pool and sports facilities.

As people come and go from the Bronx, Crotona Park remains, the prehistoric boulders that dot its landscape a reminder of how brief human life is in comparison. As Tashrak noted in 1904, just as Jews were first moving to the neighborhood and Germans were moving out:

— Written and translated by Joseph (Khayim) Reisberg, 2022–2023 Applebaum Family Fellow.

Yiddish text appears as written in digitized books, and does not conform to YIVO standard. The recording and lyrics of “Kretone Park” are shared with permission of Lorin Sklamberg. The book Bronx Accent by Barbara Unger and Lloyd Ultan was consulted, along with Yiddish titles found on OCR. Special thanks to David Mazower for his keen editorial eye.

The Bronx Bohemians blog is made possible with the support of the Lynn and Greendale families in memory of their aunt and mother, Zeva Greendale, and her special passion for yidishkayt.